Policy Brief

Inequality dynamics in China

Income growth for the poor, but more for the rich

In the late 1970s, China embarked on a major programme of economic transition and reform. Since then, China’s economy has been transformed from a socialist planned economy to a predominately market economy characterized by a combination of state, private, and mixed forms of ownership. Over the past forty years, household incomes have risen six-fold, poverty has declined dramatically, and in recent years a new class of ultra-rich has emerged. These developments have naturally led to questions about inequality trends in China.

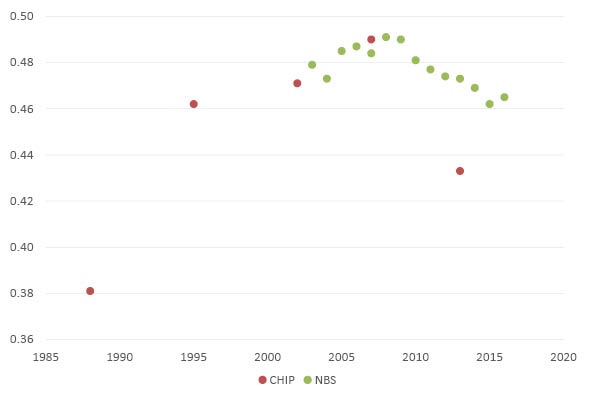

From the late 1980s through 2007, China experienced a long-term increase in income inequality. As shown in Figure 1, during these two decades China’s income Gini rose from 0.38 to 0.49. By 2007, inequality in China was at a level similar to that in Mexico and not much lower than in Brazil, countries with moderately high inequality by international standards.

From the late 1980s through 2007 income inequality in China rose from a low to a relatively high level by international standards

The twenty-year-long rise in inequality was not due to declining incomes among the poorer segments of the population, but a consequence of income increases for richer segments of the population

Standard estimates indicate that the level of inequality has plateaued and declined modestly since 2007. There is, however, a potential bias in recent estimates of inequality due to the increased difficulty of capturing China’s emerging ultra-rich class

Wealth inequality has increased substantially in China. Thus, China’s ability to transition from a high-inequality to low-inequality economy is not guaranteed

The combination of high-income inequality, the rapid rise of housing prices, privatization of state-owned enterprises and other assets, and corruption of government officials contribute to the growing wealth inequality

More recent estimates reveal that thereafter income inequality began to decline modestly. There is, however, potential bias in recent estimates of inequality due to the increased difficulty of capturing China’s emerging ultra-rich class. This raises questions about the true path of inequality in China over the past decade.

China’s twenty-year-long rise in inequality has not been due to declining incomes in the poorer segments of the population. In fact, incomes rose substantially throughout the income distribution, including for the poor. The income increases, however, were more rapid for richer segments of the population.

Trends in inequality in China are partly explained by sectoral and, to a lesser extent, regional income gaps, specifically, the widening and then narrowing of the income gaps between urban and rural areas and among regions.

China’s Gini coefficient

The trends have also been associated with underlying changes in the sources of household income and their distribution. The rise in inequality from the 1980s through 2007 was associated with a declining share of income from more equally distributed sources, especially agriculture, and an increasing share of income from more unequally distributed sources of income such as assets.

Incomplete reforms

Although China has made much progress in its economic transition over the past forty years, some aspects of the transition remain incomplete. This has significant consequences for inequality.

Well-functioning markets require strong underpinnings in the form of market regulations, corporate governance, and enforceable legal systems. In China these underpinnings are weak.

The resulting problems are most visible in asset markets. Incomplete transition in the area of property rights contributes to a growing concentration of asset wealth and income. Individuals with existing wealth, connections, or power are able to enrich themselves further. Recent studies on the distribution of wealth in China find that wealth inequality has increased substantially. The combination of high-income inequality, the rapid rise of housing prices, privatization of state-owned enterprises and other assets, and corruption of government officials all contribute to growing wealth inequality.

Incomplete reform of capital and land property markets has contributed to the emergence of an ultra-rich class and has fueled the rapid growth in their assets. China’s capital market is subject to government intervention and manipulation, enabling those close to government officials to have more opportunities to obtain loans and become successful. In addition, incomplete reform of the state enterprise sector has contributed to weak corporate governance.

Despite the substantial loosening of restrictions on migration, a variety of factors continue to impede labour mobility. The result is an ongoing segmentation of the labour market, which tends to elevate wage differentials among regions and between urban and rural workers.

Another important area of incomplete transition is rural land ownership, as rural households have only partial property rights over their farmland. This creates an imbalance between poorer rural and richer urban households in terms of their ability to benefit from their property.

Another important area of incomplete transition is rural land ownership, as rural households have only partial property rights over their farmland. This creates an imbalance between poorer rural and richer urban households in terms of their ability to benefit from their property.

Poverty reduction, despite rising inequality

How does China’s experience in dealing with rising income inequality compare to that in other developing countries? First, despite the increase in income inequality, China has not yet experienced severe social instability. This is likely due in part to the fact that, unlike some other developing countries, poor and lower-income households have enjoyed substantial income growth.

Second, evidence suggests that in recent years the expansion of redistributive policies has begun to play a role in moderating income inequality in China. Such policies are important not only because of their actual impact on income distribution, but also because of their symbolic function. They signal the regime’s commitment to a certain vision of social welfare.

Transition to low-inequality is not guaranteed

What will be the direction of income inequality in China in the future? The experiences of other countries suggest that future trends will depend on whether China is able to address several challenges.

Steps should be taken to address the widening inequality in wealth and to broaden opportunities for wealth accumulation by lower-income groups

This will require ongoing vigilance, further economic and political reforms, and strengthening and expanding redistributive policies

Direct redistributive policies should be accompanied by steps to fight corruption and the rent-seeking that results from government interventions and the political system

Incomplete market reforms encourage corruption and allow individuals with existing wealth, connections, or power to enrich themselves. There is a need to pursue measures that promote well-functioning, equitable market mechanisms

First, the segmentation of labour markets and incomplete and distorted capital markets have contributed to widening income inequality. This highlights the need to pursue measures that promote well-functioning, equitable market mechanisms. Second, direct redistributive policies must be accompanied by steps to fight corruption and rent-seeking that result from government interventions and the political system.

Third, recent encouraging trends in income inequality may not be sustainable if wealth inequality continues to rise. Steps should be taken to address the widening inequality in wealth and broaden opportunities for wealth accumulation by lower-income groups. This will require ongoing vigilance, further economic and political reforms, and strengthening and expanding redistributive policies.

Join the network

Join the network