Policy Brief

Two cheers on growth and poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa

Evidence from a 16 country study

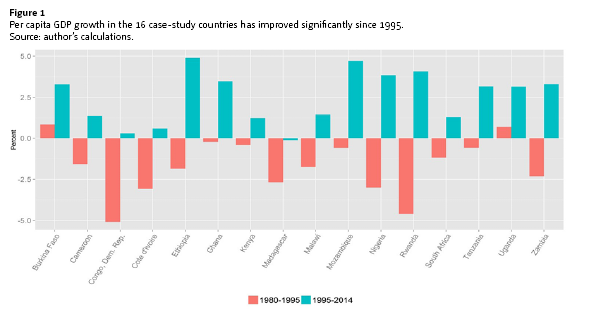

While the recovery and acceleration of economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) since about 1995 has been widely recognized, much less is known about the extent to which this growth has been translated into improvements in welfare for the population in general and poverty reduction in particular. UNU-WIDER’s Growth and Poverty Project (GAPP) therefore undertook detailed case studies of 16 of the 24 most populous countries in SSA, covering almost 75% of its population, and focusing on the last 10-20 years. Arguably, this is the most comprehensive and careful assessment of growth and poverty on the sub-continent currently available.

Progress in improving living standards in Sub-Saharan Africa has been markedly better than almost anyone expected 20 years ago. In most cases this is true for both monetary and non-income measures of wellbeing

The progress is not even and the fragility of gains over the past two decades is also evident

In much of Sub-Saharan Africa, success in growth and poverty reduction is closely linked to agricultural progress

The countries studied can be classified into four groups

1 Relatively rapid economic growth, and corresponding poverty reduction: Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Rwanda, and Uganda

A common element of this group is a sustained period of agricultural growth with participation by smallholders. Ethiopia and Rwanda illustrate important success cases where growth – based in large measure on agricultural progress – has led to significant poverty reduction. Malawi is perhaps the most controversial placement in this group, despite broadly recognized improvements in non-monetary indicators. The Malawi case study finds monetary poverty reductions that are consistent with rapid agricultural growth. It remains to be seen if this growth can be sustained.

In Ghana and Uganda, non-agricultural sectors also played important roles in bringing about poverty reduction. Ghana is emblematic of the statistical uncertainties that largely characterize the sub-continent. At the same time, there is little doubt that sustained growth occurred and that nearly all welfare indicators, monetary poverty included, improved substantially since the mid-1990s. In Uganda, agricultural growth appears to have slowed in the most recent periods with a corresponding slowdown in the pace of monetary poverty reduction.

2 Relatively rapid economic growth, but seemingly limited poverty reduction: Burkina Faso, Mozambique, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Zambia

This group provides a strong counterpoint to the first group. In all cases, evidence of sustained growth in agriculture is lacking. The case study for Mozambique points to a strong role for temporary factors influencing the most recent stagnation in monetary poverty, though a need to improve agricultural productivity, particularly among smallholders, is clearly underscored. Nigeria failed to improve non-monetary indicators despite massive oil revenues for much of the period.

The desultory state of Nigerian statistics in relation to monetary poverty preclude solid conclusions. Yet, the evidence, such as it is, does not point to strong monetary poverty reduction.

Tanzania’s tepid performance in reducing monetary poverty can be explained by the slow growth of household consumption, reflecting in part slow growth in agriculture, relatively high population growth, and food and fuel price increases. Zambia exhibits relatively little evidence of strong and broadbased gains in welfare, and some puzzles remain to be resolved. Burkina Faso faces multiple challenges including continued fast population growth and continued low productivity in agriculture.

3 Uninspiring or negative economic growth, and corresponding stagnation or increases in poverty: Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Madagascar, and South Africa

Côte d’Ivoire and Madagascar fit well within this group. Cameroon and Kenya have had relatively volatile growth records, with some periods of growth, and others of stagnation or even recession. Correspondingly limited long-run gains have been realized in many welfare indicators. Growth in South Africa has been slow relative to many countries on the continent both before and after the end of apartheid, and scope for redistribution is narrowing. The related challenges of stability and growth are front and centre for these economies.

4 Low information countries: The Democratic Republic of the Congo

The DRC remains a low-information country despite on-going efforts to improve the information base.

The importance of structural transformation, information, and capacity

A series of policy implications emerge on a continent wide basis. The need to bring about structural transformation is key, and agricultural advance will be crucial. Much concern centres as well around the small and stagnant share of manufactures in GDP on the sub-continent. Substantial growth in manufacturing value added and employment creation is indeed critical. It is also clear that employment creation goes further than this. Positive outcomes are more likely if the agricultural sector is sufficiently productive to simultaneously provide relatively inexpensive food and release labour to rapidly growing, high-productivity sectors. Adequate infrastructure underpins development in both agricultural and non-agricultural sectors, and the education system generates the necessary human capital. These issues come on top of more direct policy concerns such as reliable and reasonably low-cost power delivery, regulatory burdens, tax burdens, and speed of customs clearance.

While realistic expectations are required, the basic elements of a self-sustaining development process, as opposed to a temporary growth spurt due to favourable circumstances, are starting to come into place on the sub-continent. Forwardlooking investments to promote this growth process are merited

Policies to stimulate smallholder agriculture form an integral part of a coherent growth, poverty reduction and industrialization strategy for most countries of SSA

Importantly, the regional powerhouses of Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa are not among the better performers in terms of inclusive growth. While principal responsibility lies with country governments, the international community should consider how to promote growth and poverty reduction in these countries

Doing better on information systems in Africa is crucial to achieving development goals, not just tracking them.

To all of this comes information, a vital publically provided input and a basic condition for an informed polity in general, policy formation, and investment decisions by both public and private actors. Doing better on information systems in Africa is essential to achieving broad-based future development goals, not just looking back and tallying the score card.

While capacity constraints within governments remain, and need to be addressed, sustainable development processes demand improvements across multiple dimensions essentially contemporaneously. The sub-continent as a whole has confronted these multi-faceted challenges much better over the past 15-20 years. While the potential pitfalls are many, there is every reason to think that African development can continue to move forward over the next 15-20 years.

Join the network

Join the network