Blog

African Lions - Unpacking labor trends and growth in Mozambique

Mozambique, over the last two decades, has experienced explosive growth, with an average GDP growth rate of almost 8 percent between 1997-2015. Not only that, but, for the most part, Mozambique has a track record of solid macroeconomic policies, like controlling inflation, reducing current account deficit, and lowering the country’s dependence on aid. Like many other sub-Saharan African countries, though, the rapid growth rate has not transformed into substantially decreasing poverty rates. Indeed, while Mozambique’s poverty rates fell dramatically from 1997-2003, many experts attribute that trend to post-war recovery from the civil war that ended in 1992, no clear progress seems to have been made from 2003-09.

Mozambique, over the last two decades, has experienced explosive growth, with an average GDP growth rate of almost 8 percent between 1997-2015. Not only that, but, for the most part, Mozambique has a track record of solid macroeconomic policies, like controlling inflation, reducing current account deficit, and lowering the country’s dependence on aid. Like many other sub-Saharan African countries, though, the rapid growth rate has not transformed into substantially decreasing poverty rates. Indeed, while Mozambique’s poverty rates fell dramatically from 1997-2003, many experts attribute that trend to post-war recovery from the civil war that ended in 1992, no clear progress seems to have been made from 2003-09.

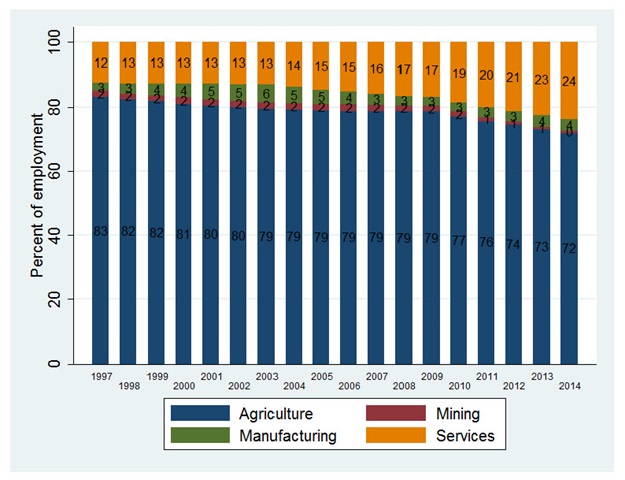

In a recent paper, Understanding Mozambique’s growth experience through an employment lens, and as part of the wider African Lions project, Sam Jones and Finn Tarp examine macro and microeconomic developments in Mozambique and apply labor market decomposition tools to investigate the disconnect between the country’s performance in growth and poverty reduction. In their study, the authors find that, while labor movement out of agriculture—like in classic structural transformation—has contributed to aggregate economic growth, this trend is over-concentrated in the services sector (Figure 1), which itself is experiencing a decrease in labor productivity.

Figure 1: Trends in sectoral shares of employment (1996-2014)

Source: Jones and Tarp’s (2015) calculations using Mozambican official statistics.

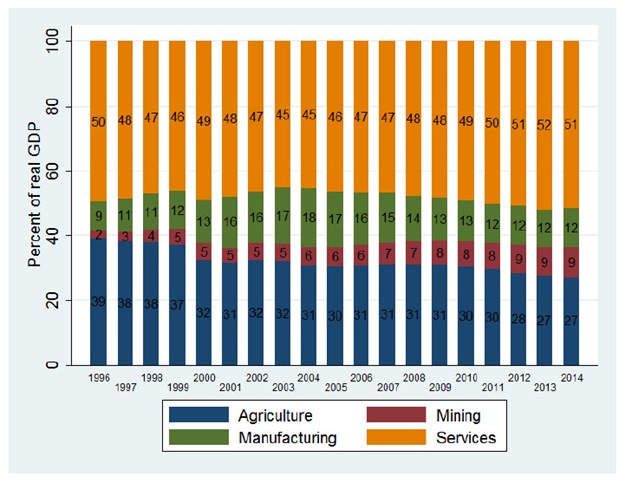

As the author’s point out, while labor makeup is changing, each sector’s contribution to GDP is only shifting a little (Figure 2), with minor changes in sectoral trends in labor productivity overall.

Figure 2: Trends in sectoral shares of real GDP (1996-2014)

Source: Jones and Tarp’s (2015) calculations using Mozambican official statistics.

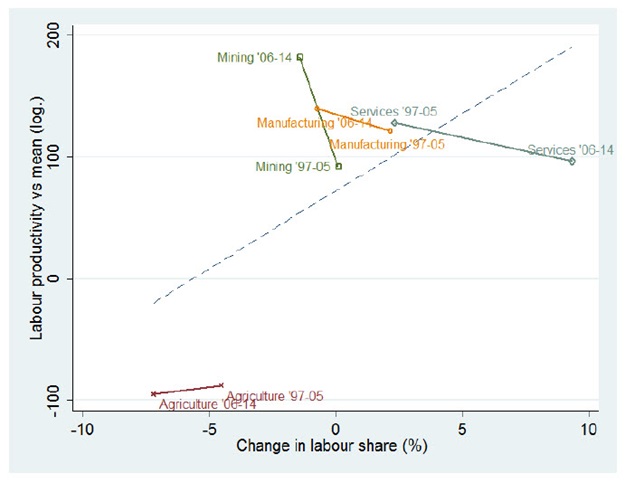

Thus, as seen in Figure 3, as the labor share for services has grown, its labor productivity has fallen. Manufacturing follows the same path, but to a more modest degree. Interestingly, as also shown in the figure, the mining sector, while slightly losing labor, has grown in labor productivity.

Figure 3: Relative labor productivity vs. changes in labor shares, by sector (1997-2005 and 2006-2014)

Source: Jones and Tarp's (2015) calculations using Mozambican official statistics.

The authors attribute the falling productivity in the services sector to the fact that “new workers in this sector tend to operate on an informal basis and undertake activities that are more precarious relative to existing workers.” At the same time, they credit the trend in mining to the lack of creation of “new employment posts in line with the pace of new entrants to the economy.” Overall, they note, “recent aggregate growth appears to have been driven by capital-intensive growth in the mining sector and by comparatively rapid growth of employment in services sector but typically in activities that have lower productivity than the sector average.”

Authors’ main findings

- Labor reallocation effects have made a relatively small contribution to productivity growth in the post-war period.

- Sectors with the fastest rates of growth in employment (primarily, services) show falling levels of relative productivity, which has not always been the case.

- Within-sector productivity growth remains to be a predominant overall contributor to productivity growth, yet is highly uneven across sectors, which raises concerns regarding the sustainability of Mozambique’s current growth path.

- Aggregate productivity growth appears to be increasingly dependent on the services sector, which, due to low productivity growth, is not translating to substantial aggregate labor productivity benefits.

Given these revelations and agriculture’s continued low productivity, how might Mozambique continue its high growth, especially in the light of the oncoming demographic dividend? The authors provide policy recommendations for continued growth. These include:

- Raise agricultural productivity through the creation of clear and stable set of incentives for private buyers, which in turn would support domestic price stability.

- Invest in rural infrastructure—especially roads—in order to foster market linkages and encourage trade and specialization.

- Minimize distortions that act against export-oriented and labor-intensive activities, such as external price competitiveness (via the exchange rate) and Mozambique’s policy of different national minimum wages for different occupational sectors.

This article originally appeared on the Brookings Institute Africa in Focus blog. Christina Golubski is Assistant Director of Brooking's Africa Growth Initiative.

The African Lions project is a collaboration among United Nations University-World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER), the University of Cape Town’s Development Policy Research Unit (DPRU), and the Brookings Africa Growth Initiative, that provides an analytical basis for policy recommendations and value-added guidance to domestic policymakers in the fast-growing economies of Africa.

Join the network

Join the network