Policy Brief

The politics of social protection in Eastern and Southern Africa

Actors, institutions and dynamics

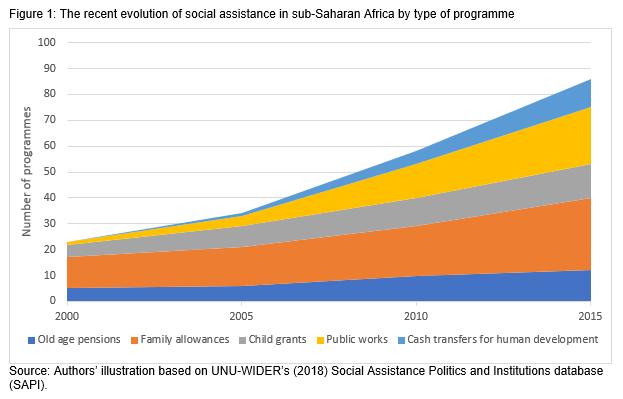

Since the mid-1990s, there has been in Africa something of a ‘quiet revolution’ in poverty reduction strategies with the proliferation of social assistance programmes that entail cash transfers to the poor. The past two decades have also been characterized by a series of important political developments that have reshaped both state–society relations within sub-Saharan Africa and its relationship with transnational actors. What lies behind these changes?

Since the mid-1990s Africa has seen a proliferation of social assistance programmes that target the poor and vulnerable

The expansion of social assistance has been driven by domestic political dynamics, reflecting the political elite’s need to ensure support and political allegiance

The evidence shows that the power of donors and international agencies working on social protection in Eastern and Southern Africa has often been overestimated

The bounded power of international organizations reflects in part the shifting financial position of African countries

Social assistance in Eastern and Southern Africa is more readily a part of the politics of patronage than a politics of ‘rightful claims’

The bounded power of transnational actors

All major international agencies involved in development have now adopted a commitment to social protection. This commitment is often seen as the source for the spread of social assistance programmes. However, this is not the case. While bilateral donors and international agencies are often perceived to have considerable power, the evidence suggests that their influence in persuading governments to implement social protection systems to scale has been limited.

For example in Zambia, social protection pilot projects operated for ten years before the national government began to expand them. In Lesotho, donors were a driving force in the partial introduction of a child grant, but not in the earlier introduction of old-age pensions. In Tanzania, the government has resisted assuming any responsibility for World Bank -initiated cash transfer programmes.

In Botswana, international organizations played no part in the introduction of old-age pensions, and the government of Botswana resisted proposals to introduce a child grant. Meanwhile, the government of Ethiopia for years resisted donor pressure to reform the emergency relief system, only introducing one when domestic political crises forced a rethink in policy. These cases underscore the fact that donor policy influence is often overestimated.

The bounded power of international organizations to push social assistance agenda reflects in part the shifting financial position of most African countries. Ultimately, the introduction or expansion of social assistance is dependent on domestic political dynamics within each country.

Social assistance as an elite survival strategy

Popular political mobilization, that is the mobilization of civilian population, has played a minimal role in the expansion of social assistance in Eastern and Southern Africa. Instead, the driving force for reform has been the need of the domestic political elites to build regime legitimacy, secure political allegiance, or win over electoral support. These survival strategies differ according to the nature of the political settlement within each country.

A clear divergence exists between those countries where political power is concentrated among a handful of political elites within a dominant ruling party (Ethiopia and Rwanda), and those in which power is more dispersed among elite groups (Uganda and Zambia).

A clear divergence exists between those countries where political power is concentrated among a handful of political elites within a dominant ruling party (Ethiopia and Rwanda), and those in which power is more dispersed among elite groups (Uganda and Zambia).

Both Ethiopia and Rwanda have adopted a developmental approach as the foundational element of their political settlements, seeking to build regime legitimacy through the delivery of a broad-based socioeconomic development, alongside the suppression of political voice outside the ruling party.

In Uganda and Zambia, the social democratic agendas are inconsistently applied, not least as a result of elite coalition building. Ruling party ideology has provided minimal support for the expansion of social assistance, as concerns about the dangers of welfare dependency resulted in significant opposition.

Appeal of social protection in electoral politics

The influence of electoral competition on policy reform in the region has been mixed. There are examples in which the general shift from dominant parties to multi-party elections has spurred campaign promises to expand the reach and generosity of social assistance.

In Botswana, the ruling Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) had long branded itself as the party of drought relief. Faced with stronger challenges from opposition parties advocating expanded public provision, the BDP moved to introduce old-age pensions and to expand its school feeding programmes and public works. Likewise, in Lesotho the social pension was introduced in a period of political dominance and stability. The pension payment rates subsequently became a focus for competition between political parties.

The case of Malawi, however, provides a cautionary tale regarding the potential of choosing the promotion of social protection as an electoral strategy. President Banda resorted to a pro-poor and pro-women social assistance brand as a key component of her electoral strategy. Though her resounding defeat had multiple causes, the results suggest limits to the political appeal of promising better social assistance.

Tensions and lessons

Tensions and lessons

When looking into the political circumstances of the expansion of social protection there are differences between countries in Eastern and Southern Africa.

On the one hand, there is evidence suggesting that authoritarian regimes can be as capable of delivering social assistance as more democratic countries. On the other hand, democratization is likely to provide incentives to make clientelism more redistributive by extending services and benefits to larger sections of the population.

Ultimately, what matters is the specific nature of state–society relations in different contexts, and what this means for elite power, citizenship, and broader issues of legitimate rule. In Eastern and Southern Africa, social assistance has become more a part of the politics of patronage than a politics of ‘rightful claims’, initially at least.

Social assistance in the region is hence both flowing from and helping to embed very different political forms, not all of which are well aligned with contemporary hopes for a new politics of citizenship and social contracts on the continent.

Join the network

Join the network