Blog

Temporary shock or lasting poverty trap?

COVID-19 in South Africa

South Africa’s COVID-19 lockdown regulations are likely to have a devastating impact on the incomes of workers and their dependents. Already disadvantaged groups will suffer disproportionately from the adverse effects. Low-income earners performing jobs in precarious, informal sectors of the economy without unemployment insurance, limited access to healthcare, and no back-up savings, are especially at risk. The government’s decision to top up the monthly social grants as a temporary relief measure during the COVID-19 pandemic was an important step in the right direction, but the actual distributions are significantly lower than was previously estimated.

The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have long-lasting effects on people’s livelihoods.

Even in normal times, about 70% of those who experience downward mobility in South Africa enter a situation of structural poverty that is difficult to escape from.

In a recent WIDER Working Paper, I use a mix of quantitative and qualitative research methods to illustrate the complex processes, livelihood strategies, and asset dynamics that condition movements into and out of structural poverty in South Africa, with special attention given to the urban population.1 While conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, the main messages emerging from this research remain highly relevant in the current situation.

Across urban South Africa, the chances of moving up the income ladder are characterised by ‘sticky floors’ and ‘sticky ceilings’. Except for the most and the least well-off, there is considerable mobility across income levels. However, for roughly half the people who start off from a situation of structural poverty and experience a rise in incomes, the escape from poverty is stochastic (or random), characterised by a limited accumulation of assets that could help facilitate successful long-run escapes from poverty.

Conversely, close to 70% of those who start off non-poor and experience downward mobility fall into a situation of structural poverty, where assets have been significantly depleted. Thus, among households with few buffers to protect their living standards, negative shocks to income can easily generate a poverty trap, which it is difficult to escape from. This gives rise to concerns that the COVID-19 pandemic may not only present a temporary shock, but have lasting implications for poverty rates in South Africa through its effects on people’s health, education, and employment prospects.

Job transitions are among the main trigger events associated with poverty entries and exits

To better understand the building blocks that either pave or bar the way for structural poverty transitions, I conducted 30 life-history interviews between July and September 2017 in the township of Khayelitsha, situated about 30 kilometres south-east of Cape Town’s city centre.2

Two main patterns were repeatedly observed:

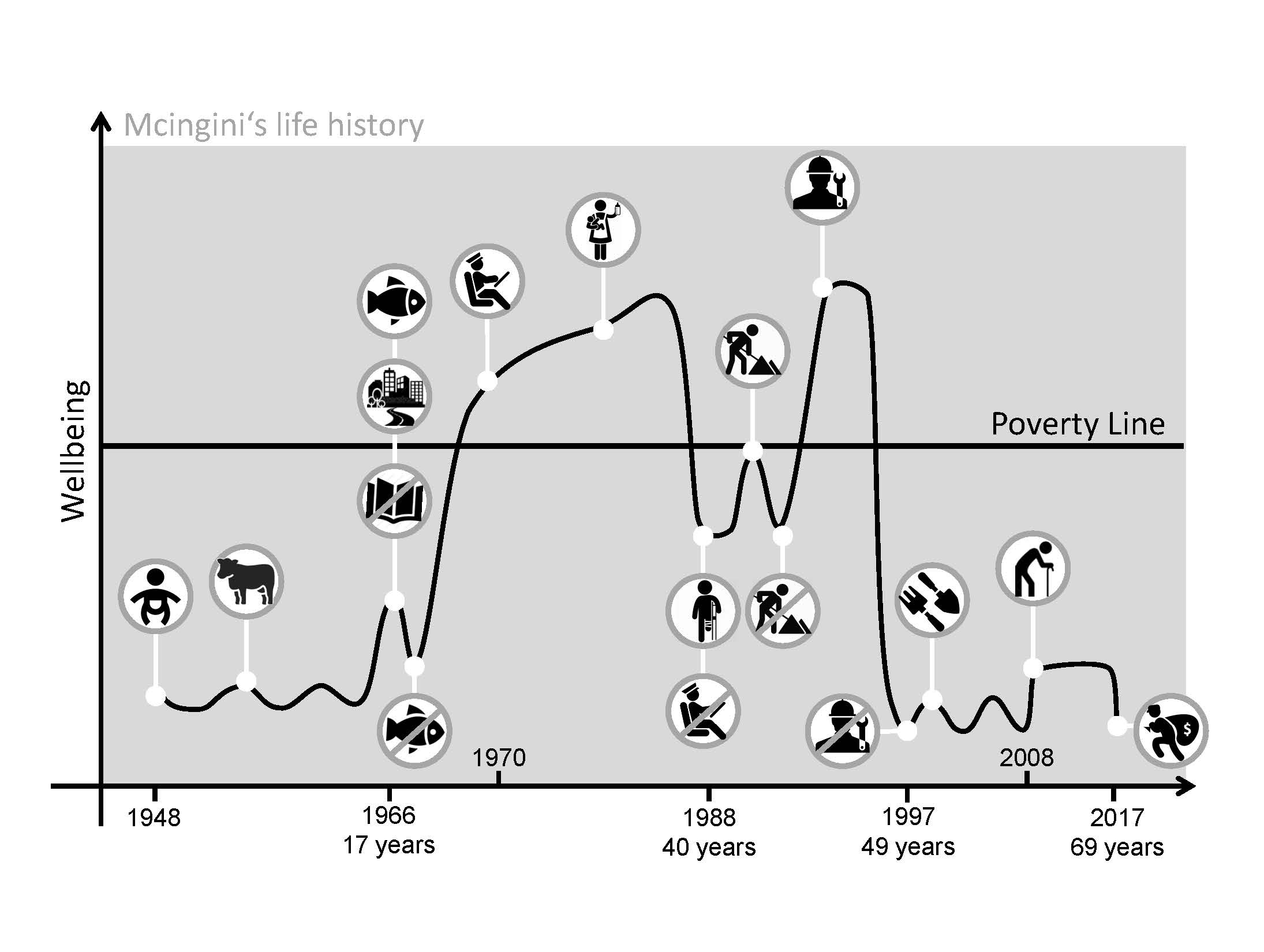

- In contrast to those who remained structurally poor, those who experienced structural upward mobility were integrated into better-functioning family networks and were more successful in seizing opportunities to enhance their human capital, especially by gaining relevant work experience and certifications. They experienced an important gradual improvement in their standard of living, often facilitated by successful job-to-job transitions, with only short spells of unemployment in between. Importantly, at least some of these jobs were kept for prolonged periods of time (10–20 years). Mcingini’s3 story summarised below illustrates this pattern. It also illustrates the vulnerability of those in jobs that are sufficiently well-paid but which come without social security coverage.

- In cases of a structural descent into poverty, the impoverishment tended to occur in multiple linked steps, constituting a downward spiral. Respondents often experienced an accumulation of several negative and often inter-related events, which included job loss, sickness, the death of a close family member, being a victim of crime, experiencing the destruction of household property, domestic violence, and alcohol or drug abuse.

Summarising, transitions into or out of employment and job-to-job transitions were among the main trigger events associated with both poverty entries and exits. Functioning family networks, educational attainment, and work experience presented key facilitating factors in this regard, while health shocks, crime, and domestic abuse were among the main risk factors.

The COVID-19 pandemic may not only present a temporary shock, but have lasting implications for poverty rates in South Africa through its effects on people’s health, education, and employment prospects, as well as potential knock-on effects from increasing rates of crime and domestic abuse. The pandemic may not only have short-term income effects, but also hamper people’s income generating activities in the longer term, as households will turn to liquidating their small savings and selling off productive assets to cope during the lockdown period. In addition, reduced food consumption in times of hardship, school closures and the constraints that poor children face in online teaching can have a negative effect on human capital formation which can have long-term negative effects on earnings. For the millions of vulnerable South Africans whose livelihoods hang in the balance, an ambitious commitment by the state to confront these challenges will be decisive.

| LIFE HISTORY – SOUTH AFRICA |

|---|

|

Mcingini was born in 1948 in the Eastern Cape. He grew up with both his parents and seven siblings in a simple stone house in the mountains. They had a kraal, but the number of cattle fluctuated as a result of droughts and veterinary infections. At the age of 17 years, he left school and moved to Cape Town in search of work. He found a job as a fisher and was sending money home. The contract ended after six months and he started moving from one temporary job to the next, working in different low-skilled occupations. In 1969, he got a job as a driver at a factory; he says he taught himself how to drive. He worked there for almost 20 years. During this time, he got married and his wife opened a crèche at their home, such that there were two incomes. In 1988, Mcingini fell sick and had to leave his job and move back to the Eastern Cape. He was supported by his older brother for three years. After his health had improved, he moved back to Cape Town and started working at a construction site. When the contract ended, he found a job as a mechanic after a short period of unemployment. In 1997, he lost this job. Since then, he was only able to find piece jobs as a gardener, but retired from this in 2006, because he would get no more jobs (people told him he was too old). Since 2008, he is receiving the state old-age pension. In 2017, they were robbed at their house.

|

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors

Join the network

Join the network