Blog

35 years of research for change – what's next?

Building just societies

To celebrate its 35th birthday, UNU-WIDER has looked back at some of its greatest achievements. As the year closes, Armida Alisjahbana, Kunal Sen, Andy Sumner, and Arief Yusuf highlight the continued impact of UNU-WIDER’s flagship work and the future of knowledge about building more just societies.

UNU-WIDER’s inaugural director — the senior Sri Lankan civil servant and Keynesian economist, Lal Jayawardena — was deeply committed to equity. He helped create collective organizations to realize developing countries’ demands and he was an advisor to the Brandt Commission. As Amartya Sen summed up, Lal ‘wanted to build a society that would be foundationally more just’.

The developer’s dilemma

One of the challenges of building a society that is foundationally more just was identified by pioneers of development economists, such as Simon Kuznets, who feared that economic development would lead to an upswing in income inequality.

To build societies, economies need to undergo a process of ‘structural transformation’ — when production transitions from lower-productivity to higher-productivity activities. Conventionally, this has been understood as a transformation from mostly agricultural production to mostly manufacturing and is indicated by the large-scale movement of workers from low- to high-productivity sectors of the economy.

While this process is crucial to generating sufficient wealth to improve human wellbeing, it seemed to Kuznets – and other early development economists such as W. Arthur Lewis – that it would lead to upward pressure on inequality, at least in the near term, because economic development processes, as Lewis pointed out, start unevenly. Some areas and people benefit before others. This implies that government policies are essential to counteract upward pressure on inequality and spread the benefits of development wider, from dynamic, modern activities to other sectors of the economy. In the words of Lewis’ ‘trickle-along’, not trickle-down.

... rising inequality during economic development is not inevitable and development can, indeed, be inclusive.

This tension between building an economy and who benefits in the earlier days is what we call ‘the developers’ dilemma’. The questions that flow from the dilemma are about how to manage any trade-offs and which public policies can help.

In the UNU-WIDER project, culminating in a forthcoming book, we take a look back over the period since Lal directed UNU-WIDER and ask how are developing countries to promote economic development – building a society – whilst also spreading the benefits of development broadly by addressing income inequality?

What do we find?

The key findings come from the project’s multi-country examination of development trajectories, and nine in-depth country case studies led by national research teams. We find three things:

First, we find multiple pathways of economic development with different inequality dynamics.

Second, we find that rising inequality during economic development is not inevitable and development can, indeed, be inclusive. But, broad-based economic development requires public policies to address any upswing in inequality. This is exactly what Kuznets argued in his seminal paper, but this has been mostly lost in the excessive focus on the infamous, inverted-U curve.

Third, economic development does, as Lewis pointed to, start unevenly. Hence, public policies are needed to address the divergences in income that may arise. In other words, more trickle-along is needed.

In short, to echo Lal’s thinking, building a society that is foundationally more just requires public policies to address the left-behind.

Building a society: multiple pathways of economic development

Kuznets, Lewis, and others envisaged one pathway of structural transformation in the form of industrialization. We find, when we consider the empirical pattern of structural transformation in the developing world, there are a set of pathways or ‘varieties of structural transformation’.

We find that countries experience one of these five stylised pathways, which we name as follows: ‘primary industrialization,’ ‘upgrading industrialization’, ‘advanced industrialization,’ ‘stalled industrialization,’ and ‘secular deindustrialization’ (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Varieties of structural transformation

Of course, it is important to note that not all developing countries fit neatly into this typology. More precisely, these varieties are not suited for the very poorest highly aid-dependent developing countries that remain largely agrarian or those heavily dependent on the mining sector. A separate analysis is needed for these countries.

It is also important to note that countries are not fixed within the variety of structural transformation to which this analysis has assigned them. Shifting between different varieties is possible and, in some cases, desirable.

India is an exemplar of primary industrialization. India’s industrialization between 1990–2010 was more evident in employment shares than in value-added shares, thus it is defined as primary – meaning labour-intensive – industrialization. China exemplifies, par excellence, – upgrading industrialization. Value-added and employment shares were substantially higher in 2010 compared to 1990. Indonesia is an exemplar of stalled industrialization. During one long period from 1980 to the late 1990s (up to the Asian financial crisis), both employment and value-added shares increased rapidly. However, the increasing trend suddenly stopped in the late 1990s. The shares stagnated during the first half of the 2000s before starting to decline in the mid-2000s. Finally, Brazil serves as an exemplar of premature deindustrialization. From 1990 onwards, premature — earlier than other countries — deindustrialization becomes clear.

... broad-based, or inclusive, economic development requires public policies to address any upswing in inequality and spread the benefits of economic development to people and areas left behind.

The distinct trends across these four exemplars illustrate how much the contemporary question of economic development can differ. For India, the major challenge is to sustain labour-intensive primary industrialization for some time in order to absorb the increasing labour force and devise a strategy to bring forward the transition to upgrading industrialization. For China, the major goal is to accelerate the process of upgrading industrialization and prepare for the economic and social consequences of phasing out labour-intensive manufacturing as the country seeks to enter the phase of advanced industrialization. For Indonesia, the challenge is to return to the upgrading industrialization it experienced before the late 1990s. A failure to do so would mean the beginning of premature deindustrialization. For Brazil, policies are needed to shift the country towards advanced industrialization.

Building a just society: the inequality dynamics of economic development

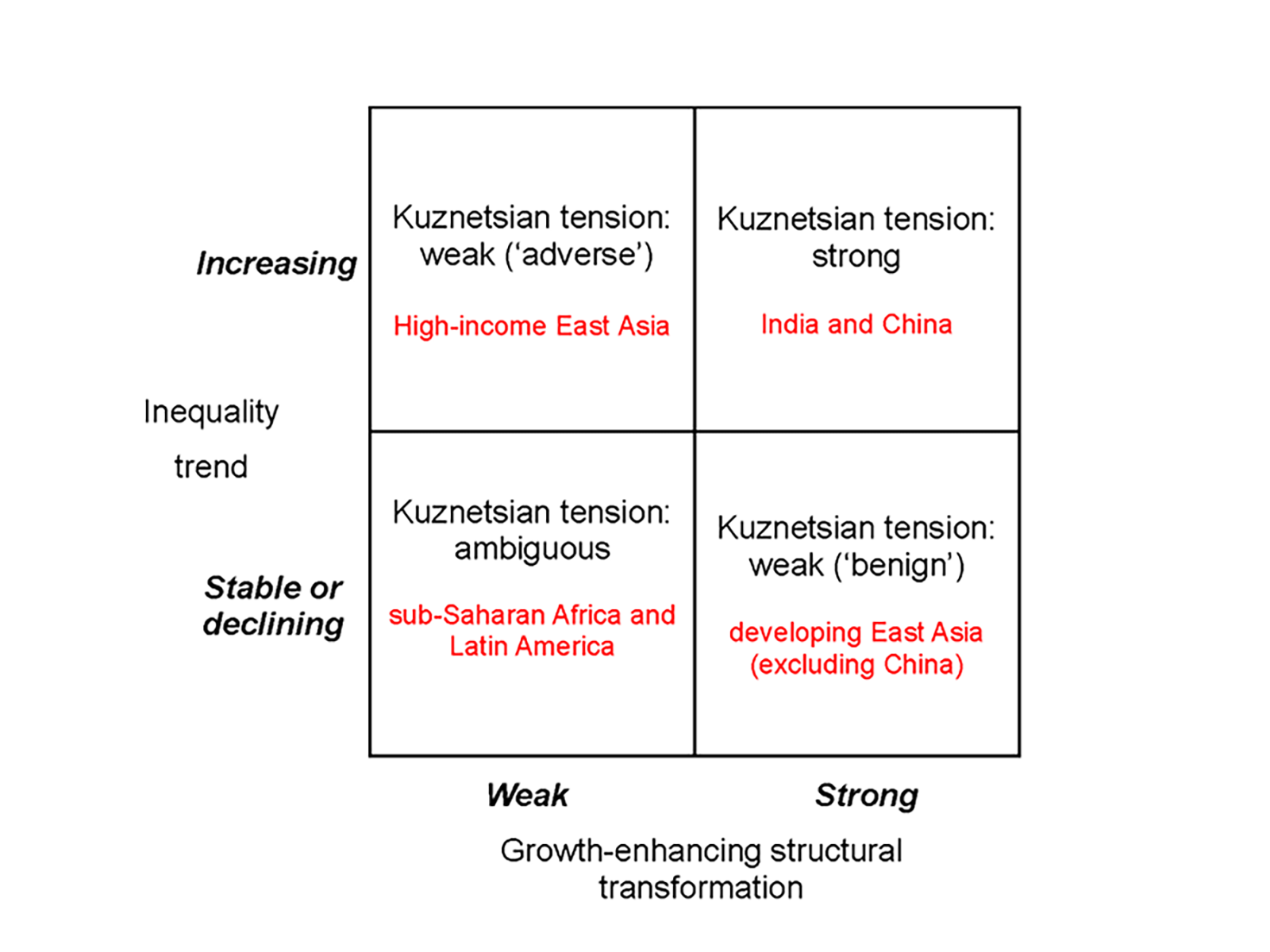

We also find that the inequality dynamics differ by types of economic development. We summarise the experiences we find in Figure 2. The trend in income inequality is on the vertical side (i.e. stable/declining inequality or increasing) and the strength of structural transformation (i.e. weak or strong) is on the horizontal.

Figure 2: The developer’s dilemma: income inequality trends and structural transformation

Each quadrant tells a different story about the developers dilemma. For example, we can say that India and China have experienced a strong tension as inequality has risen alongside structural transformation. We can say developing East Asia (excluding China) has experienced a weak and benign Kuznetsian tension, as it has managed stable inequality with strong growth-enhancing structural transformation. In contrast, across Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa there has been an ambiguous tension, in that inequality has been stable as structural transformation has been weak. Finally, we can say high-income East Asia fits in the weak or adverse tension quadrant of rising inequality accompanied by weak growth-enhancing structural transformation.

What would UNU-WIDER’s first director make of all this?

What would Lal Jayawardena make of all this? Or for that matter Simon Kuznets or Arthur Lewis? Each were in their own ways dedicated to identifying strategies for developing countries to build societies and more just societies. Each would thus be surprised at the multiplicity of structural transformation beyond the ‘traditional’ pathway. Each would likely pick up on the fact that rising inequality during economic development is not inevitable and seek to bury that falsehood once and for all. Finally, each would remind us that they had written themselves on how broad-based, or inclusive, economic development requires public policies to address any upswing in inequality and spread the benefits of economic development to people and areas left behind. In sum, to echo Lal’s approach, public policies remain essential to not only building a society, but to building one that is foundationally more just.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network