Blog

The zero carbon agenda and metals demand: some major dilemmas

The transition to net zero over the next few decades will involve a large increase in the global demand for many metals essential to the renewables revolution driving that transition. Recent research by the World Bank has identified a minimum of 17 main metals needed in significant quantities for that purpose: all six of its scenarios indicate significantly increasing demand through 2050.

For example, three of the International Energy Association (IEAs) scenarios used in the report indicate total demand increasing from around 45 million tons annually in 2020 to as much as 180 million tons by 2050 under IEA’s most ambitious climate scenario, and to over 160 million tons annually in its less ambitious one. There is little doubt that most renewable energy sources are far more material-intensive than traditional fossil-fuel systems.

These include wind turbines, solar panels, and, especially, batteries for electric vehicles (EVs) and large-scale energy storage (needed to reduce the intermittency of energy from wind and solar). And, to that we can add in all the other uses of metals to reach net zero, not least in buildings, IT equipment, and so forth. While more material can come from recycling and reuse, the demand for most metals is projected to far exceed current supply.

Consequently, de-carbonisation does not mean de-mineralisation. Yet this immediately raises the questions: where will the many extra metals and minerals come from and what are the implications?

Mining has shifted from North to South

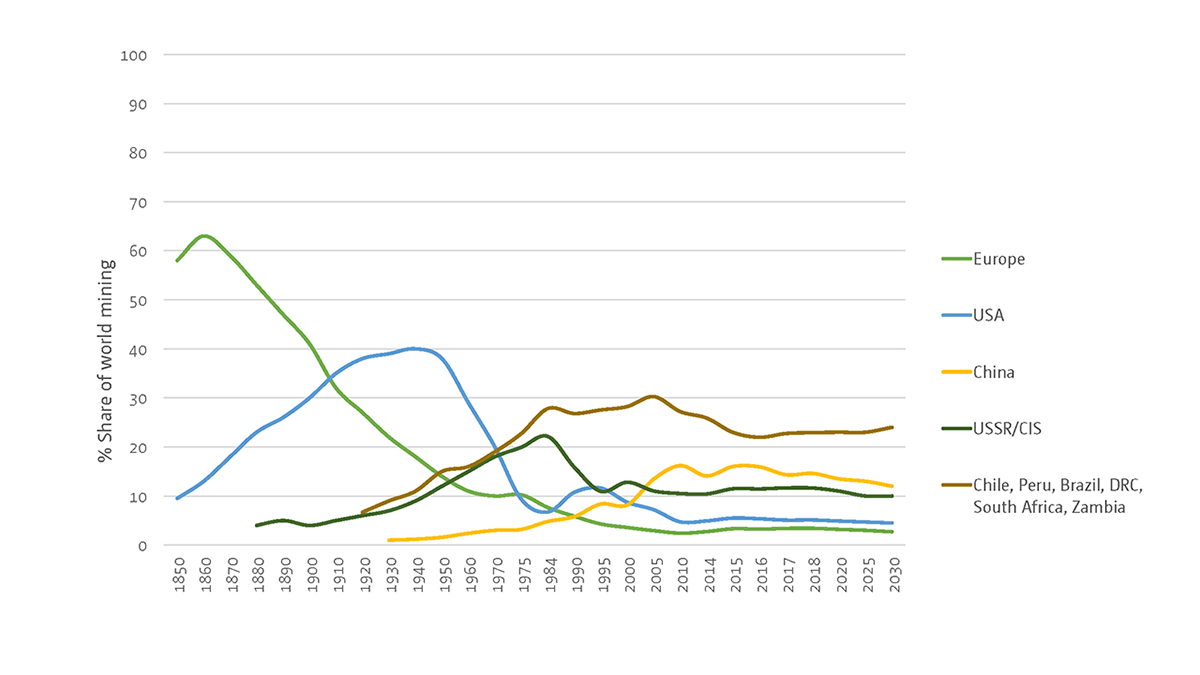

The past century has seen a dramatic decline in the share of global mineral production from Western Europe and the USA (Figure 1). In the years between the two world wars both Europe and the US had shares of global production of around 40% each. In both cases, these shares are now down to roughly 5%. Mining is now very much an economic activity located in the developing world.

Figure 1: Value of mined production (excl. coal) – share of world total

This has now set off alarm bells in the EU and the US, especially over a sub-set of so-called critical metals. For example, a 2020 Report from the EU Commission identified 30 critical raw materials (mostly metals and minerals) where it sees a high level of dependency. It notes that the EU now sources 98% of its rare earths from China, 71% of its platinum from South Africa; and 78% of its lithium from Chile. Similar degrees of mineral dependency are seen in the USA.

The EU and the USA are taking some small steps to stimulate domestic mining, at least of critical metals. The EU’s Horizon 2020 initiative funds innovations in the mining sector and the US Department of Energy issues grants to stimulate production of certain critical metals.

Corporate plans for new mining activities are also increasingly in the news: lithium in the UK’s Cornwall; a potentially huge geothermal lithium facility in the Upper Rhine valley in Germany; a possible large Rio Tinto Zinc (RTZ) boron/lithium plant in Serbia; and even a new rare earths processing facility in the UK’s Yorkshire.

The Green Dilemma

Mining can cause serious environmental damage and is itself a large user of energy, especially when supplied by coal- and gas-fired power stations. Greenhouse gas emissions associated with primary mineral and metal production have been estimated at approximately 10% of all energy-related greenhouse gas emissions worldwide. Furthermore, this figure is increasing over time as more difficult mines and decreasing ore grades require more energy to produce the same quantities of metals.

The shift of mining from North to South — together with metals refining and aluminium and steel manufacture — contributes to emissions reductions in Europe and the US, but adds substantially to the emissions of countries in the Global South.

As one Canadian mining expert bluntly puts it: ‘we have knowingly and patiently created a system that allows us to move our filth as far away as possible ... We can thank them (i.e., the new suppliers such as China) for the environmental damage they have endured to produce these metals in our place’ (Pitron 2020: 71).

This is especially evident in relation to rare earths. These elements are used in every high-tech device of our daily lives, including the equipment needed for the net zero transition itself. Yet, they are inherently toxic, their extraction involves huge water and soil/rock displacement, and their radioactive residues have a very long half-life.

In the early 1980s, the world’s two biggest rare earths producers were the Rhone Poulenc facility in western France and the huge Molycorp facility in the Mojave Desert in California. Both succumbed to the combined pressures of Chinese competition and increasingly rigorous environmental standards in Europe and the US.

The growing need for metals and minerals to run the global economy and achieve the net zero transition now poses an acute green dilemma. The advanced economies can carry on burnishing their own local green credentials by relying on the developing world to supply their material needs, and continue to turn a blind eye to the associated environmental damage. Or, they could try and encourage rigorously regulated mining at home (and use renewable power sources wherever possible), in which case they need to convince environmental campaigners and local communities.

For this to work, delegates at the upcoming COP26 Summit need to be persuaded that some new mining in the EU and the US may be a better carbon solution than the alternatives. For example, utilizing Cumbrian coal for essential steel production in the UK will be far less carbon-intensive overall than importing coal from, say Poland.

Or, the advanced economies could, together with China, provide finance and technology to help rapidly shift mining in the developing world away from harmful environmental practices and towards ‘green mining’. COP26 delegates should encourage those lower-income countries endowed with the critical mineral resources to expand their production of these as part of their drive for the SDGs. This will further imply the crucial need to commit significant donor finance to making the mining and metals production sectors of these countries as green as possible. That is no small task and — together with a possible carbon tax — implies higher costs right across global value chains. None of this is easy, either economically or politically, whichever direction is taken.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network