Blog

Overcoming the challenge of illicit financial flows

Four pieces of advice for policymakers

From profit shifting to sanction evasion, illicit financial flows divert funds away from essential poverty-fighting and infrastructure programs. A growing body of research provides essential insights for policymakers on how to tackle this key development challenge.

Illicit financial flows (IFFs) are a major development challenge for countries in the Global South. Developing countries lose money and their economies weaken due to these illegal transactions of money across international borders.

IFFs lead to unfair competition for domestic firms, cause governments to misallocate economic resources and facilitate tax evasion, which increases inequality and may decrease citizens’ general willingness to pay taxes. IFFs also allow criminals and human rights violators to escape sanctions.

Thanks to improved data sources, research on IFFs and the Global South has grown significantly. These studies’ findings can help policymakers tackle this critical problem. In this post, I break down the topic of IFFs into four sub-categories and provide policy recommendations on each.

Preventing companies from profit shifting through tax havens

Profit shifting is a complex issue that has garnered significant attention in recent years. It involves multinational corporations shifting their profits to low- or no-tax jurisdictions to reduce their tax burden. Governments worldwide lose revenue.

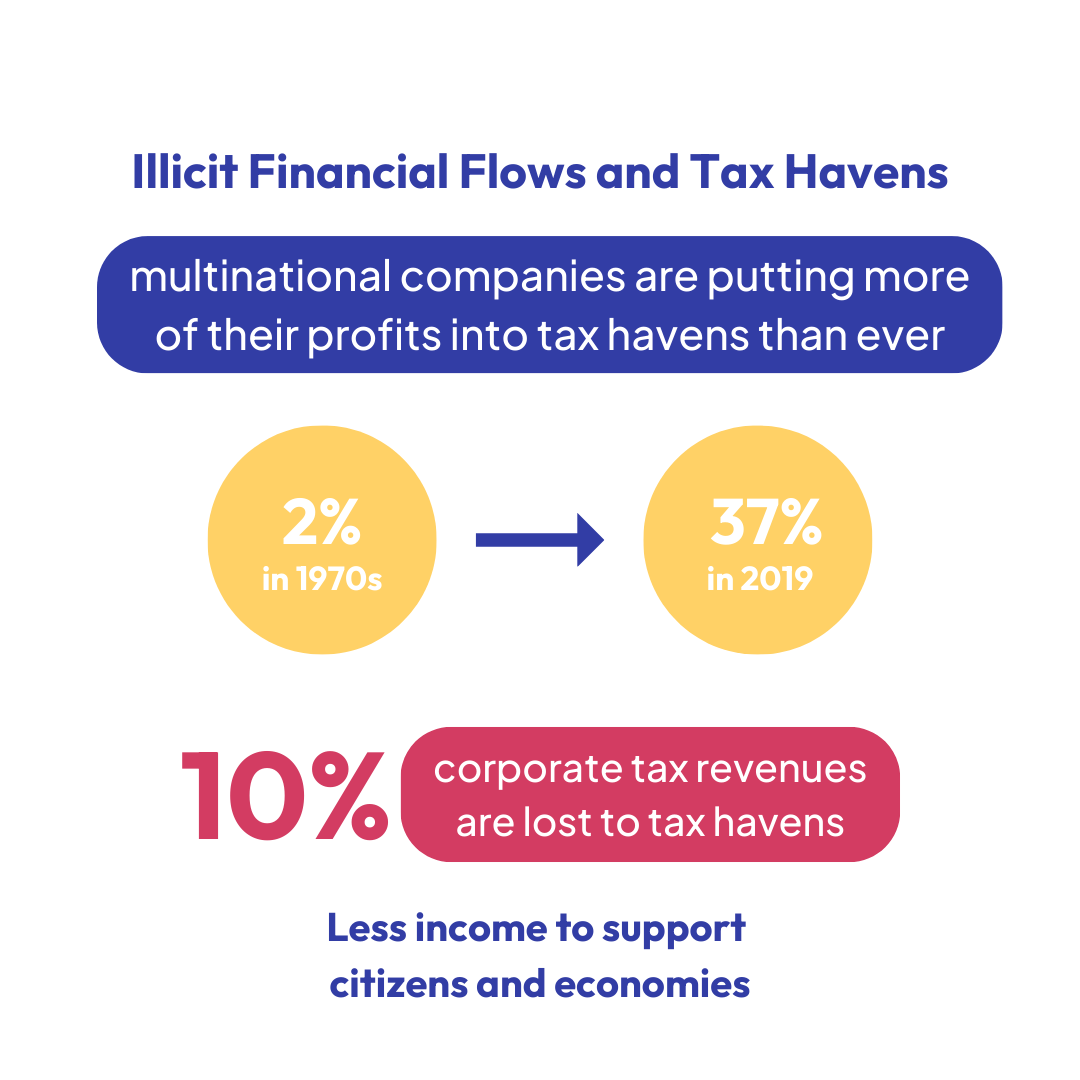

The world has been trying to curb profit shifting for a decade. But a recent United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics (UNU-WIDER) study shows that the share of multinational profits shifted to tax havens grew from less than 2% in the 1970s to 37% in 2019. Globally, 10% of corporate tax revenues are lost as a result, reflecting a leaky bucket of funds for lower-income countries.

Important policy takeaways emerge from this and other recent research findings:

First, multinational corporations operating in the Global South tend to shift profits through so-called Offshore Financial Centres (OFCs). To fight this, governments should consider taxing intangible assets, export intensity, external commercial borrowing, and other party transactions. More policy advice related to OFCs is found in this working paper.

Second, countries should use publicly available data on international trade and new methodologies to better target regulations on trade flows. These tools could also enable better detection of transfer mispricing. Companies often use this trick – which manipulates the price of traded goods or services – to avoid taxes.

Third, multinational corporations might also use internal debt for profit shifting. To counter this, governments need to limit the amount of tax-deductible costs.

Fourth, countries can increase their domestic corporate tax revenue by focusing audits on companies that have a high-risk of profit-shifting behaviour, which they can identify through transaction-level data.

Furthermore, the significant growth of global corporate profits in relation to global income underlines the need for governments to ensure that corporate tax revenues keep pace with company profits.

Lastly, it is advisable to promote the implementation of the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) process, the US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and the United Nations level initiatives to mitigate profit shifting. While the effectiveness of these initiatives is subject to debate, these initiatives may have helped prevent further increases in profit shifting.

Combating sanction evasion

Policymakers often use sanctions as a foreign policy tool, for example, to curb human rights violations or discourage a country from waging war. They include trade restrictions to asset freezes and travel bans. Recent research uncovers several ways in which countries manage to bypass sanctions, by exchanging goods in secret, for instance, and the consequences of this evasion.

To make international sanctions more effective, governments need better enforcement mechanisms. If they could mitigate financial secrecy (where individuals or firms hide their finances to evade the law), they would be able to better identify cases of sanction evasion, particularly by human rights violators and dictators. Additionally, placing sanctions on neighbouring countries who trade with the sanctioned nation would help limit evasion.

Moreover, implementing rigorous monitoring methods that use more fine-grained trade data would bolster the enforcement of trade sanctions.

Finally, the research demonstrates how trade sanctions’ effects on labour markets hit the poorest members of society the hardest. Poorly educated workers are more likely to be forced into jobs in the informal sector when a decline in international trade takes away their old jobs. This dimension needs more consideration and action.

Dealing with corruption and unwillingness to pay tax

Corruption significantly undermines the development of countries in the Global South. According to a recent journal article, some 5–10% of the aid from the World Bank flows to financial accounts in offshore tax havens upon disbursement. Enhanced monitoring mechanisms are necessary to prevent local elites from diverting these funds to tax havens.

It is also crucial for governments to consider how international aid affects tax morale – that is, people’s willingness to pay tax – in the recipient country. For example, research shows that when governments prioritize funds for projects that build state capacity, citizens’ tax morale improves – and more than when funds are focused on other types of projects. Morale also improves when funds come from multilateral donors, rather than from unreported financial flows.

By implementing these measures, development partners can use international aid more effectively, ensuring it has its intended impact.

Detecting hidden wealth and mitigating IFFs: policy evaluations

Many governments have taken actions to detect hidden wealth and mitigate tax-avoidance. Several papers published by UNU-WIDER consider the effectiveness of increasing the tax price of sending dividends to havens to eliminate the anonymous ownership of property, tax amnesties, and mandatory disclosure rules on transactions.

A wide range of policy implications emerge. First, policies that increase the tax price of sending dividends to tax havens induce a clear increase in domestic reporting, even if set in place by only one country. In other words, they encourage people with financial connections to tax havens to declare additional capital income on their tax returns. They pay a higher income tax rate as a result.

Second, property ownership transparency policies are efficient in fighting tax evasion. This is provided the reporting requirements lead to a public database that is subject to public scrutiny, and if they come with strong enforcement capacity.

Third, tax amnesties can increase total wealth reported and tax revenues. Fourth, mandatory disclosure rules involving intermediaries effectively increase deposits.

State capacity is needed to implement such policies, but they appear to be effective. This underlines further the need for development co-operation to concentrate on building state capacity, including support to combat financial secrecy.

These policy measures provide a helpful framework for tackling IFFs, and subsequently for enhancing domestic corporate revenue. Implementing these measures will contribute to a fairer and more transparent international tax system while promoting sustainable development.

Finn Tarp is a Professor of Development Economics at the University of Copenhagen and a Non-Resident Senior Research Fellow at UNU-WIDER.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network