Blog

Improving early child development outcomes in low-income settings

Improving early child development outcomes in low-income settings requires affordable, sustainable, and easily scalable solutions. The “First Steps” programme in Rwanda has substantial positive effects on child development and offers a blueprint for interventions seeking to improve parental practices.

Millions of children in low-income countries risk not reaching their development potential due to extreme poverty and deprivation. These children accumulate development deficits from a young age that are transmitted across generations generating persistent poverty traps. Early child development (ECD) interventions that improve cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes among young children may help breaking these poverty traps (Heckman 2006, Gertler et al. 2014).

Parenting programmes that address such poverty traps have become popular in recent years. However, much of the evidence on the impact of ECD interventions comes from advanced economies and middle-income countries with well-functioning welfare systems that are able to incorporate these programmes into their structures, and with fairly efficient bureaucracies that support their implementation and targeting (Attanasio et al. 2020, Doyle 2020, Sylvia et al. 2021). Such interventions may not be affordable, sustainable or easy to scale up in low-income countries – where the need for such interventions is most acute. Governments in low-income countries face a myriad of budget and institutional constraints that may prevent the implementation of complex ECD programmes in ways that target those in need effectively. In addition, low-income parents face a multitude of challenges when trying to secure the survival of their families and may not have the time, resources and knowledge needed to engage in such programmes.

To address these constraints, Save the Children designed a unique low-cost, low-intensity and short-duration ECD programme – First Steps or Intera za Mbere. The programme was designed alongside the Government of Rwanda and Umuhuza, a Rwandan NGO. The evaluation of this programme (Justino et al. 2023) shows how a modest intervention to strengthen knowledge about parenting practices, and how to act on that knowledge, can improve child well-being and parent-child engagement considerably among some of the most vulnerable communities in the world. The cost per caregiver per session of First Steps ranged between $1.94 and $2.11, which is considerably lower than other ECD interventions elsewhere in the world, generating short- and medium-term impacts comparable to those more complex interventions.

First Steps is a group-based parenting intervention implemented during 17 weekly meetings among parents of children aged 6-24 months living in remote communities in the (rural) Ngororero district in the Western province of Rwanda. Almost half of the population of Ngororero lives under the national poverty line and over one-fifth of the population is classified as extreme poor (NISR 2016). Stunting among children under five years old is around 56%, compared to 38% nationally (DHS 2015).

First Steps was designed to address the specific needs of such communities in several ways. First, to address literacy and education constraints, the First Steps team designed and implemented an innovative radio drama aired during group meetings, instead of relying on standard parenting training methods using reading materials. Each radio episode focused on a key parenting practice and its viewing was both preceded and followed by a group discussion with trained facilitators recruited from each village. Second, First Steps tried to facilitate the diffusion of ideas and information, strengthen peer-to-peer learning and reduce costs by focusing on community level actions, such as group discussions, shared childcare and training of community facilitators, rather than the more widely used home visits in such parenting interventions. The use of community facilitators was also intended to improve trust between families, communities and the programme. Third, the programme activities were conducted around family daily routines (for instance, encouraging parents to talk to and play with children while cooking or working in the fields) and made use of common household resources as learning tools, in order to minimise the impact of the programme on time and budgetary constraints faced by low-income families.

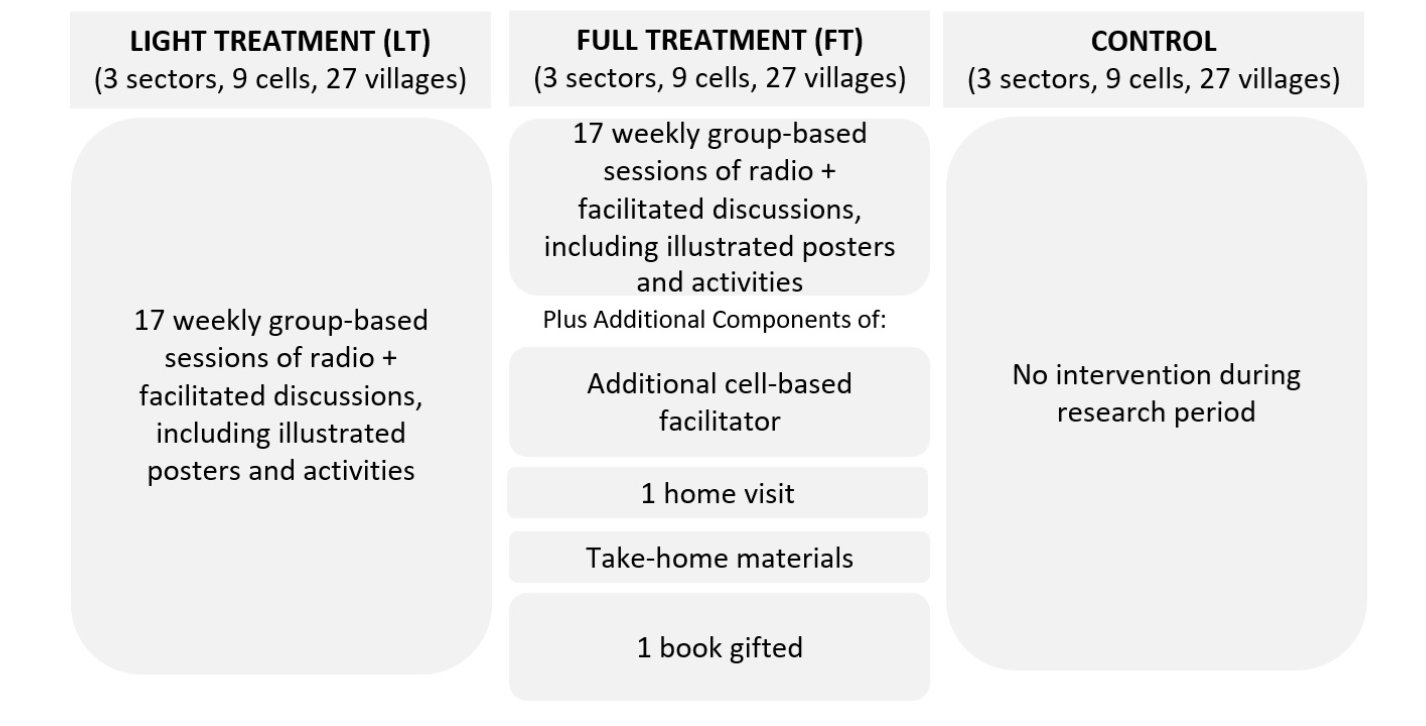

The evaluation of First Steps was based on a cluster-randomised controlled trial with two treatment arms and a control group. In the first treatment arm, parents attended the 17 weekly group meetings (which included listening to the radio drama). In the second treatment arm, in addition to the group meetings, parents received extra inputs in the form of a second supervising facilitator, one home visit and a children’s book. The programme started in November 2015 and ended in April 2016. Baseline, endline and follow-up data were collected, respectively, in August 2015, September 2016 and May 2018 (almost three years after the initial implementation of the programme). Our study highlights three important results that offer important entry points for how the Government of Rwanda, and governments elsewhere in low-income countries, may want to scale-up the programme at the national level.

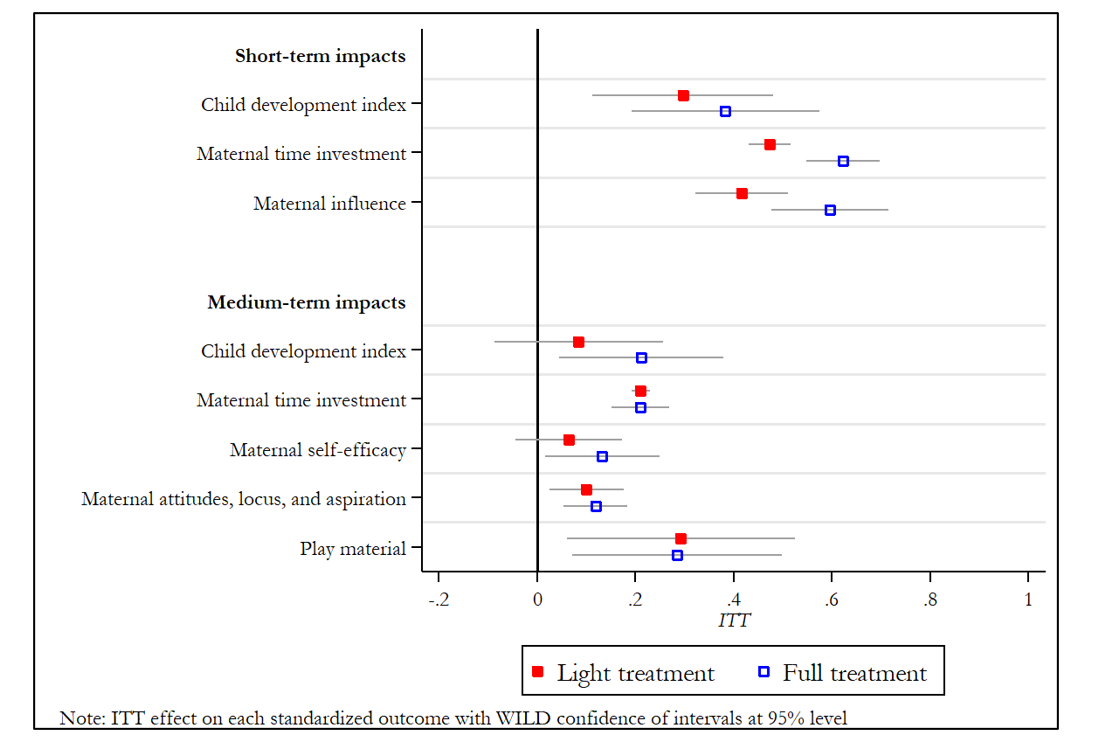

First, both treatments show a positive and substantial impact of First Steps on several child development outcomes (communication ability, gross and fine motor skills, problem solving and social interaction) after 12 and 33 months, respectively. The average index of child development outcomes increased by 0.3 standard deviations (SD) in the first treatment arm and by 0.4 SD in the second treatment arm 12 months after the intervention. After 33 months, the second treatment arm still shows increases of 0.2 SD. These size effects are comparable to other well-known parenting programmes implemented in higher income settings.

Second, we find large short- and medium-term impacts of both treatment arms on parental time investments – an important result given the low-income, low-literacy and remote context in which the programme was implemented. There are also notable positive results of First Steps on perceived maternal efficacy, attitudes towards gender roles, locus of control and aspirations – key normative changes that arguably may support further positive human capital development over the longer term.

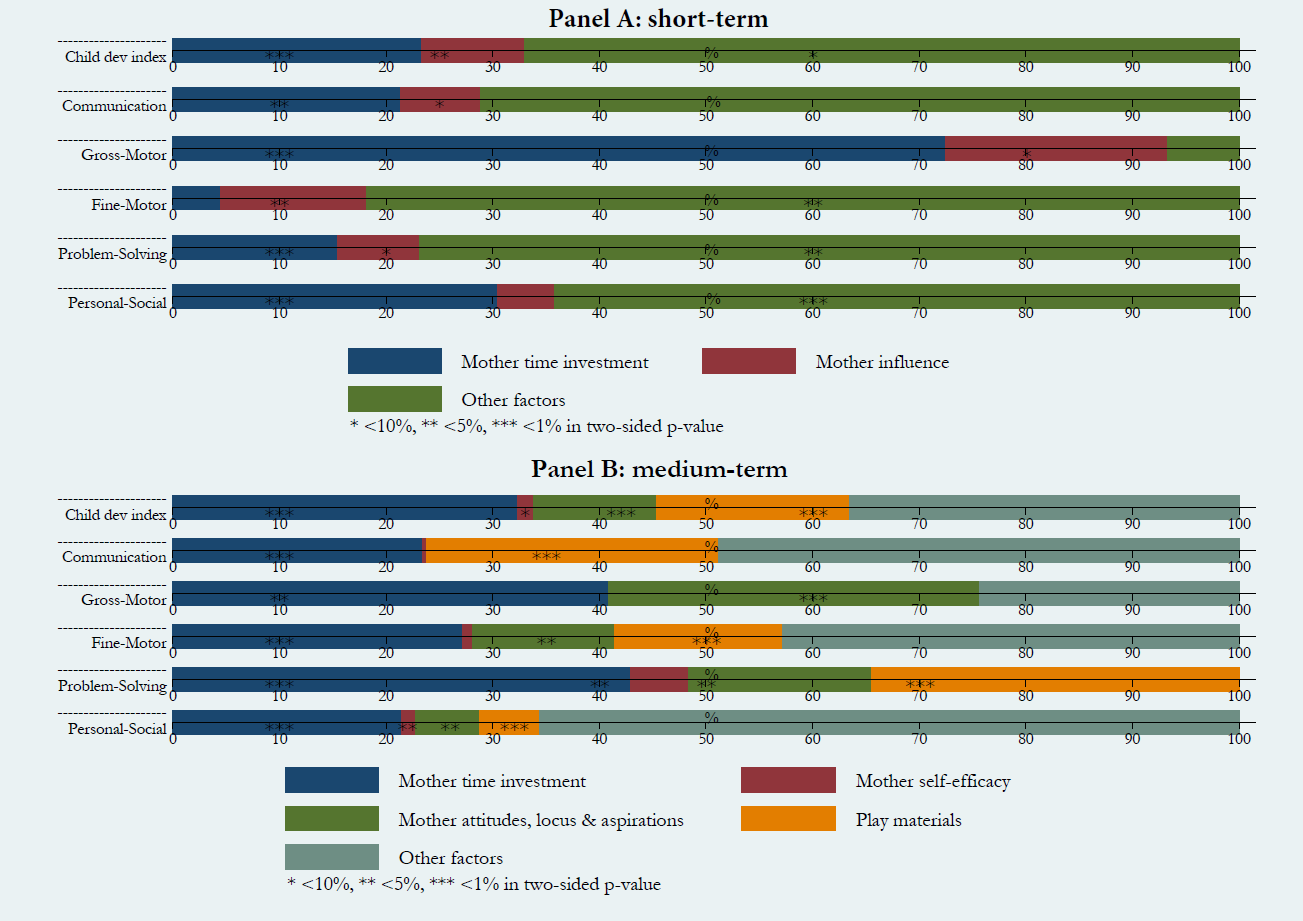

Third, we show that the considerable effects of the programme on child development outcomes are driven by improvements in two important factors. The first is an improvement in maternal time investments, which translates into between 20 and 35% of the short- and medium-term impact of First Steps, respectively. The second factor is an improvement in material investments, which accounts for around 20% of the medium-term impact of the intervention. Other less substantial mechanisms (but still significant, accounting for about 10% of improvements in child development) are improvements in maternal attitudes, in locus of control and in aspirations for their child.

Taken together, these results show how meaningful changes in parental practices and behaviours can be achieved to improve substantially child development indicators among severely deprived communities through a modest intervention that can be easily replicated and scaled-up. We hope this study will offer actionable entry points for similar interventions in other low-income countries with constrained financial and institutional capacity, but in dire need of addressing poverty traps driven by adverse lifelong accumulation of human capital, without the need of integrating into existing large national welfare programmes.

References

Attanasio, O, S Cattan, E Fitzsimons, C Meghir and M Rubio-Codina (2020), “Estimating the Production Function for Human Capital: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial in Colombia”, American Economic Review 110(1): 48-85.

DHS (2015), “Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2014/2015 – Western Province”, DHS Report, National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, Ministry of Health and ICF International.

Doyle, O (2020), “The First 2,000 Days and Child Skills”, Journal of Political Economy 128:2067-2122.

Gertler, P, J Heckman, R Pinto, A Zanolini, C Vermeersch, S Walker, S M Chang and S Grantham-McGregor (2014), “Labor Market Returns to an Early Childhood Stimulation Intervention in Jamaica”, Science 344: 998-1001.

Heckman, J (2006), “Skill Formation and the Economics of Investing in Disadvantaged Children”, Science 312: 1900-1902.

Justino, P, M Leone, P Rolla, M Abimpaye, C Dusabe, D Uwamahoro and R Germond (2023), “Improving Parenting Practices for Early Child Development: Experimental Evidence from Rwanda”, Journal of the European Economic Association 21(4): 1510-1550.

NISR (2016), “The Fifth Integrated Household Living Conditions Survey”, NISR Report, National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda.

Sylvia, S, N Warrinnier, R Luo, A Yue, O Attanasio, A Medina and S Rozelle (2021), “From Quantity to Quality: Delivering a Home-Bsed Parenting Intervention through China’s Family Planning Cadres”, Economic Journal 131: 1365-1400.

Patricia Justino is Deputy Director at UNU-WIDER and Professorial Fellow at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) in Brighton, UK (on leave).

Marinella Leone is Associate Professor at University of Pavia.

Pierfrancesco Rolla is a teacher the World International School in Turin, Italy, and Research Consultant.

This article was originally published by VoxDev and republished with permission. Read the original article.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network