Policy Brief

Poverty in Mozambique

Significant progress but challenges remain

In 1990, Mozambique was one of the poorest countries in the world, with poverty estimated to reach 80% of the total population. At that stage, a Millennium Development Goal of reducing this proportion by half posed a very difficult target to meet. After the ‘war of destabilization’ in 1992, and particularly from the beginning of the new millennium, Mozambique experienced stronger growth and stability. Yet from 2002/03 to 2008/09 poverty reduction stagnated. From 2008/09 to 2014/15, the Mozambican economy kept growing at a similar, stable pace. The question that needed to be answered was then: what had happened to poverty?

National poverty rates estimates are in the range of about 41–46 percent of the population, reflecting between 10.5 and 11.3 million absolutely poor people

At the national level, welfare levels have improved compared with the results of prior surveys

The gains have not, however, contributed to a convergence in welfare levels between rural and urban zones or by geographical region

Measuring poverty and wellbeing

The Ministry of Finance of Mozambique, supported by UNU-WIDER and Copenhagen University, put forward a comprehensive analysis of poverty and wellbeing based on the 2014/15 Household Budget Survey, conducted by the country’s National Statistics Institute (INE). Results from this latest survey were compared to those obtained in previous survey rounds — 2008/09, 2002/03 and 1996/97.

Poverty and wellbeing were considered across an array of dimensions and using two principal approaches: the first focusing on consumption; the second relying on multidimensional methods for assessing poverty and wellbeing. The indicators employed were drawn from the four household budget surveys, and relate to education, health, housing, and possession of durable goods.

Poverty reduced, but regional inequality persists

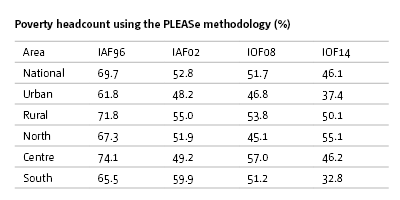

Across all approaches, a coherent story emerges. At the national level, welfare levels have improved compared with the prior survey undertaken in 2008/09. National poverty rates estimates are in the range of about 41–46 per cent of the population — reflecting between 10.5 and 11.3 million absolutely poor people.

Issues with data made the estimates of consumption poverty less precise than desired. Nevertheless, using the official data (no correction for undercounting of consumption in any year) poverty declines by more than five percentage points compared with 2008/09.

Issues with data made the estimates of consumption poverty less precise than desired. Nevertheless, using the official data (no correction for undercounting of consumption in any year) poverty declines by more than five percentage points compared with 2008/09.

The gains have not, however, contributed to a convergence in welfare levels between rural and urban zones or by geographical region. Very substantial differences in welfare levels persist. The gap between rural and urban zones is large and at best persistent (if not aggravating). Living conditions in the south are much better than those in the north and the centre across almost all welfare dimensions considered and all methods (partly due to a higher level of urbanization in the south compared with the north and centre). In addition, inequality of consumption has been increasing since 1996/97. The rate of increase has most recently also spiked.

From a regional perspective, poverty reduction was rapid in the southern provinces, where the rate fell by about 18 percentage points, led by Maputo province. Reductions were significant but less rapid in the centre where rates fell by about 11 percentage points. These reductions are distributed quite evenly across the four central provinces. These gains were offset by an increase of an estimated ten percentage points in the north, with the greatest increases occurring in Niassa province.

Essentially, all the principal trends identified in the consumption poverty analysis are also reflected in the multidimensional analyses. Results from multidimensional poverty analysis point to strong gains from 2008–09 and very strong gains from 1996–97. As noted, these gains are generally not succeeding in reducing disparities between rural and urban zones and between regions/provinces. Living conditions are notably better in urban zones and in southern provinces.

Essentially, all the principal trends identified in the consumption poverty analysis are also reflected in the multidimensional analyses. Results from multidimensional poverty analysis point to strong gains from 2008–09 and very strong gains from 1996–97. As noted, these gains are generally not succeeding in reducing disparities between rural and urban zones and between regions/provinces. Living conditions are notably better in urban zones and in southern provinces.

What does this mean for policy-making?

These results — both the suggestion of a very positive performance at a national level and the evidence of increased rural–urban and inter-provincial inequalities — show that balanced, spatial, economic, infrastructure and social policies are becoming increasingly critical from both welfare and political economy perspectives.

The informal sector will be of fundamental importance to achieving continued broad-based progress in welfare enhancement over at least the next decade

Nearly half of the Mozambican population is under 15 years of age, and high dependency ratios will continue at burdensome levels for a generation or more

Achieving inclusive growth is the core policy challenge facing Mozambique in its economic and social development over the next decades

The findings in the Mozambique Fourth Poverty Assessment Report inescapably imply that future dynamics in smallholder agriculture and the informal sector will be of fundamental importance to achieving continued broad-based progress in welfare enhancement over at least the next decade, and likely longer than that. Nearly half of the Mozambican population is under 15 years of age, and high dependency ratios will continue at burdensome levels for a generation or more. The same goes for the future provision of much-needed social and other public services, particularly health and education. In sum, achieving inclusive growth is the core policy challenge facing Mozambique in its economic and social development over the next decades, where it will strive to make significant progress towards meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as agreed at the United Nations in September of 2015.

This Policy Brief, also available in Portuguese (disponível em Português), draws on Mozambique’s Fourth National Poverty Assessment.

Join the network

Join the network