Blog

Bride price or dowry?

Why is it that in some countries the parents of a bride pay dowry, whereas in some others the groom has to pay for the bride? What is the impact of different traditions on women’s lives?

Marriage payments, as well as dowry or bride price, are still in use in 75% of countries globally. Bride price refers to a situation where the groom alone, or with his family, makes a wedding payment to the bride’s family in the form of livestock, money, commodities, or other valuables. In addition to this, the groom’s side is required to have the resources for the wedding party, and mostly a house as well into which the new wife can move. Therefore, before the marriage, the future groom has to be prepared to cover notable expenses. For example, in Zambia, the expenses of getting married can amount to a year’s income.

The bride price differs from the dowry tradition that is better known in Finland. While in bride price tradition the groom executes a payment to the parents of the bride, in the case of the dowry it’s the opposite way around. The marriage payment traditions have been found to exhibit varying harmful side effects depending on the direction of the payment.

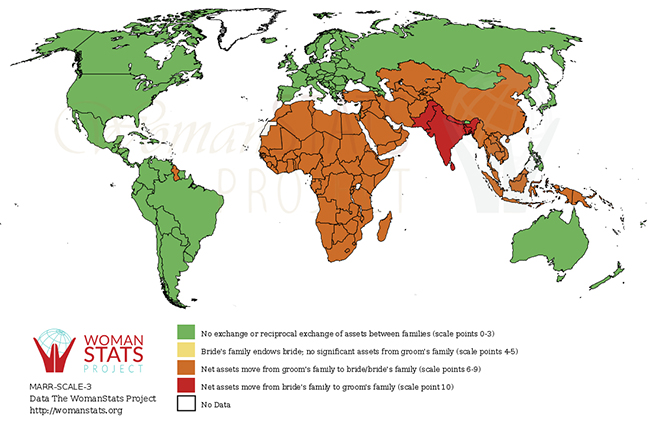

The bride price tradition is significantly more common than the tradition of dowry (see Figure 1: red colour shows countries still following the dowry tradition and orange for countries following the bride price tradition). However, in India, the dowry tradition is still strong. Furthermore, there the bride and her family are forced to save considerable amounts of money to ensure a marriage — possibly amounting to 4–8 years’ income. In India, the savings are often invested in gold, so the global price of gold plays an important role in the marriage market.

Figure 1: Bride price / dowry / expenses of marriage (types and distribution) in 2016

For instance, Bhalotra et al. have shown that when the price of gold increases the mortality of girl babies and foetuses also rises. The expensive dowry tradition is seen to contribute to the distorted gender ratio in India.

What determines the direction of payments?

Researchers have suggested different theories for why in some countries dowries dominate while in others bride price is mostly in use.

The Western utility theory suggests that bride price is in use especially in the patriarchal countries with patrilocal living arrangements, where the demand for female and child labour force has been especially high and where less sophisticated farming technologies have been in use. Typically, the bride price is suggested to be paid to the parents of the bride in exchange for the future labour inputs of their daughter and her unborn children, as the bride moves away from her parents to cohabit and work on the husband’s estate and not the other way around. The used farming techniques have been suggested to play a significant role in what direction of the marriage payments flow.

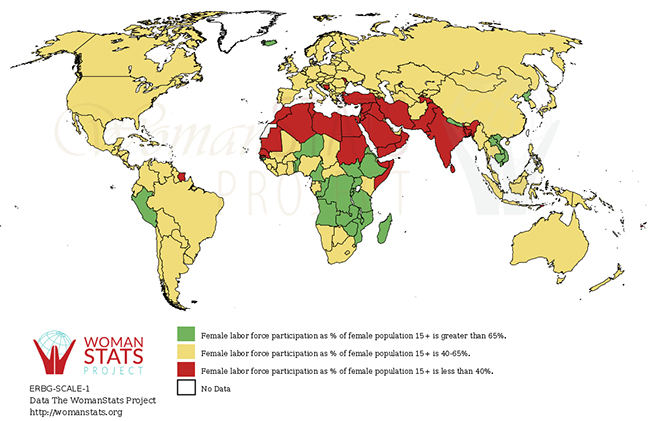

In Africa direct (manual) sowing has traditionally been the preferred farming method. Direct sowing does not require a heavy plough, a simple hoe suffices. This method, easily applicable for women and children, is still in use in small-scale farming and women’s labour force participation rate is high even today (e.g., the rate is 80% in Tanzania), while in India for instance, the female labour participation rate has declined to 20% (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Female labour force participation as % of female population 15+, scaled 2018

In India, and Finland, farming has been mostly based on heavy ploughing which demanded the physical labour input of able men, which partly explains the dowry tradition (direction from bride's family to the groom) of these countries. With time, new methods were found for ploughing (draft animals), but in Africa, these methods were not developed further to the same extent, due to the effectiveness of the direct sowing method.

Bride price is an older tradition

Researchers have also suggested that the bride price — a tradition which is about 3000 years older than the dowry — would have been in use typically in primitive, often somewhat egalitarian tribal and nomad cultures. Transition to the dowry tradition has been said to indicate the transfer into more developed, more complex social structures and classes.

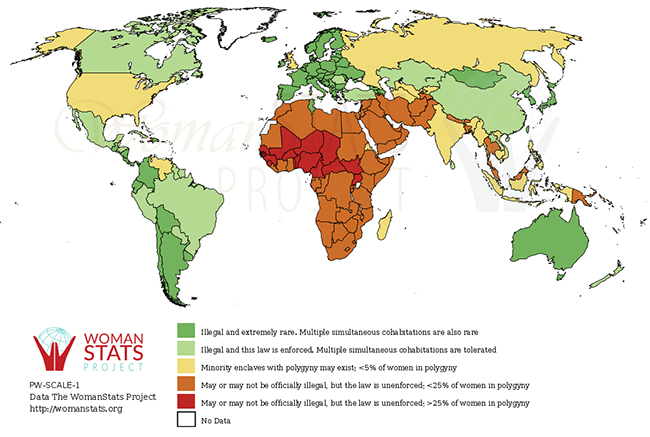

On the other hand, the bride price tradition has also been suggested to be related to the practice of polygamy and the relative amount of men and women available on the marriage market. Polygamous communities (see Figure 3 for global prevalence) might end up with a lack of single women in case one man could marry several women without any restrictions such as the bride price. And married men usually need to pay even a bigger compensation for a new bride than is normal. In Africa, in particular, polygamy seems to correlate strongly with the tradition of bride prices.

Figure 3: Prevalence and legal status of polygyny

Other key functions have been developed for bride prices too. It is seen as an important ritual that ultimately seals the marriage. Over time, bride prices have become a useful tradition for male emancipation. A high payment is an expensive pledge that guarantees the wife will remain in the marriage, as it is often almost impossible in low-income conditions for the parents to reimburse the received assets and funds. In patriarchal communities where the responsibility for childcare is in practice entirely with women, safeguarding the presence of women in the household is important, which also reinforces the bride price tradition.

For those living in poorer conditions, bridal price is an effective way for a bride’s family to make money. Through an extensive statistical analysis, Corno and Voena (2020) showed that a negative income shock such as a drought is associated with a higher number of child marriages.

Indeed, bride price is seen as an important reinforcing factor in the prevalence of child marriages. Furthermore, young wives are marketed as more obedient and easier spouses. They also have a longer work career and fertile period ahead compared to their older sisters. In many cultures, bride price has also had strong linkages to purchasing girls’ purity. In Tanzania, 25–30% of marriages are child marriages, even though child marriages are unconstitutional.

The fact that a woman is paid for makes her an object or even a commodity, which ultimately could fulfil the characteristics of human trafficking, making women an easier target of exploitation within the family. A recently developed branch of literature has explored the link between bride price and violence. On the one hand, some evidence suggests that men feel more justified in beating their wives if, after getting married, they are disappointed with their ‘expensive investment’ that does not live up to their expectations related to, for example, getting children. So bride price in a way allows for harmful behaviour because it ensures a woman has a higher threshold to get a divorce. To address the problem shelters have been set up for women, and a few countries have enacted laws to prevent the redemption of the bride price in the event of a divorce

On the other hand, in the society at large, especially in poor contexts, the scarcity of funds needed for marriage has been shown to drive some men to violent behaviour or to the significant postponement of marriage.

Bride price tradition increases the motivation to educate daughters

Scholars still disagree on whether bride prices are a beneficial or a harmful tradition. Part of the literature suggests that women are happier and tolerate domestic violence less with higher bride price.

Education has also long been seen as a factor raising the price paid for the bride. When the daughter is educated, she can be considered to be more productive, which means the bride’s family will correspondingly ask for a higher price for giving her away. Indeed, Ashraf et al. (2020) have shown that in Indonesia and Zambia, communities that follow the tradition of bride price are more eager to send their daughters to schools when such become available, compared to those equivalent communities that do not have the bride price practice in use.

In a collaborative project supported by the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs, with Ayu Pratiwi (University of Turku), Kunal Sen (UNU-WIDER), and Ralitza Dimova (University of Manchester) we have studied the tradition of bride prices and its various consequences in Tanzania. We have access to longitudinal data, unique at the African scale, that can be used to study long-term links (1991–2010) between bride prices, their components and characteristics, and, among other things, health, psychological variables and consumption. The data can be used to monitor an individual from childhood to adulthood. The dataset is also relatively rich, allowing us to effectively rule out various distorting factors.

Our preliminary findings show that high prices have different effects. On the one hand, the high price paid seems to have a positive link with women's higher self-esteem, even years after the payment. Indeed, qualitative research evidence states that women typically remember the price that was paid for them the rest of their lives and value themselves accordingly: ‘I am valuable, I made good money for my parents when I got married’.

On the other hand, however, we found that high prices are associated with a lower sense of control, even after years. This supports the idea that the kin and especially the husband and his family control the woman more, the higher the price they have paid for her. As in previous studies, we also found preliminary evidence that higher prices have a positive correlation with accidents experienced by women at home, a measure used widely as a proxy for domestic abuse, even years after the wedding.

While marriage payment traditions can be considered to include some benefits, in the end in many countries there is a general hope that over time the bride price tradition will turn into a symbolic gesture or a token. Achieving this will require a better understanding of the phenomenon and, consequently, stronger regulation, especially in those areas where the most harmful side effects occur.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network