Research Brief

Can trade in services bolster regional development in Southern Africa?

Service exports are the fastest growing portion of world trade and now account for nearly a quarter of global exports. Tradable services contribute to economic growth and development by bolstering industrial capabilities, facilitating productivity growth and investment, and contributing directly to exports. This presents opportunities for many emerging economies to enter new markets.

Services are playing an increasing role in global production and trade

Growth in tradable services supports the growth of traditional exports, driving economic growth more broadly

Southern Africa has yet to develop strong regional markets in tradable services and in the higher value-added service industries commonly referred to as ‘knowledge-intensive industries’

Consequently, the potential for tradable services to enhance growth and development in Southern Africa is yet to be realized

A growing role for services

There are four key reasons to increase trade in exportable services. First, technological change has enhanced the tradability of services via the spread of digital technologies and the declining cost of air travel.

Second, knowledge-intensive services are a key ingredient in raising productivity and competitiveness across other sectors. Service provision strengthens other industries by upgrading their capabilities, adapting products to new markets, reducing waste, and facilitating trade.

Third, higher-order services can enhance the position of regions in global value chains by capturing bigger shares of value-added services in marketing, customization, and after-sales support.

Finally, advanced design and engineering services can help economies adjust to a whole series of disruptive new technologies related to artificial intelligence, robotics, and the ‘internet of things’.

New evidence on trade in international services for Southern Africa

Compiling reliable evidence on the contribution of tradable services across Africa is hampered by differences in the way services are measured and major gaps in international trade data. However, a new dataset that uses mirror data (matching of recorded exports and imports between countries) and recent advances in statistical modelling have enhanced cross-country comparability for the period 1995–2012.

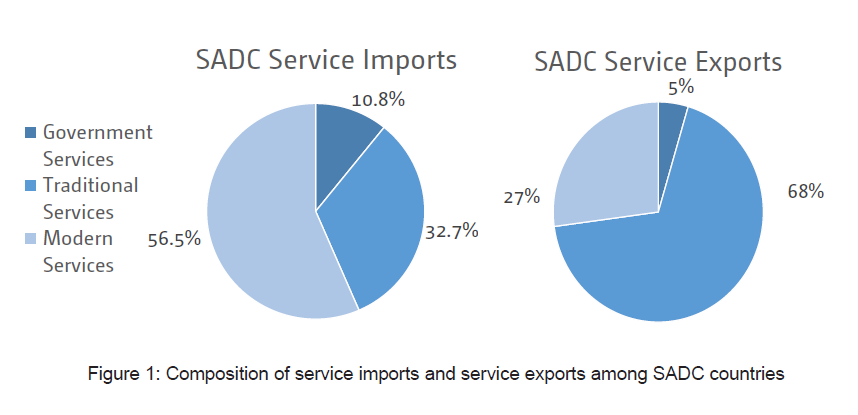

Over this period, services were not a significant proportion of Southern African Development Community (SADC) exports — they were typically less than 15% of each country’s trade balance and concentrated in lower-value (‘traditional’) sectors like transport and travel. Knowledge-intensive (‘modern’) service activities — such as IT, finance, and business services — showed some signs of growth, but remained small in absolute terms.

Services exports from SADC countries therefore lagged behind domestic growth, rather than leading or driving it. Consequently, the potential for tradable services to enhance growth and development in Southern Africa has not yet been realized.

Africa as a regional trade bloc in services?

Instead, SADC countries import sizeable amounts of advanced services. This is a missed opportunity for local development and indicates that there is potential for African firms to replace non- African suppliers if local competencies can be nurtured.

Recent regional trade agreements, such as the SADC Trade in Services Protocol, the Tripartite Free Trade Area, and the African Continental Free Trade Area, include opportunities for a growing trade in services. Their ability to deliver these opportunities depends on determined follow-up action by governments, industry, and professional organizations.

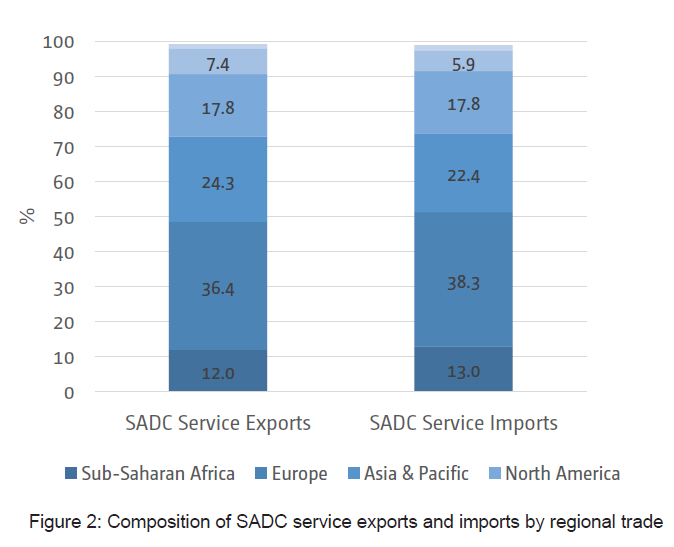

Close examination of the latest balance-of-payments trade data shows little sign of regional integration across African countries. Firms from SADC countries were far more likely to export services to European markets than to their African neighbours (see Figure 2).

Supplementary evidence from South Africa’s foreign direct investment in the region shows the potential for mutually beneficial inter-regional development. Leading South African firms in financial services, telecommunications, engineering, and property have succeeded in continental markets. However, these investments appear to follow from physical market proximity and market size rather than membership in the SADC community.

Lessons for policy

These findings imply that the role of service industries needs to be recognised more explicitly and factored into domestic industrial and trade policy.

The supposed policy choice between supporting manufacturing or supporting services is false considering their co-dependence and complementarity. Knowledge-intensive services should be recognised for their strategic role in raising productivity and adding value to other sectors.

Regional trade agreements should seek to develop regional specializations, whereby clusters of related firms benefit from a shared pool of proficient labour, know-how, technology spill-overs, and specialized infrastructure.

Governments should start by listening to private industry in order to understand their needs and priorities. It matters a great deal whether the growth of tradable services is mainly constrained by trade barriers, state regulations and bureaucratic procedures, or by the restrained mindsets, strategies, and internal capabilities of firms themselves.

Listening to private firms in a sector-specific way can help identify barriers to growth in tradable services

Governments should take practical steps to exploit opportunities created by trade agreements

Tradable services should be explicitly included in trade and industrial policy

Trade and regulatory barriers that reduce firm-level capabilities should be strategically diminished

The availability, quality, and detail of services trade data in African countries should be improved in line with WTO guidelines

The collection of international services trade data in African countries needs to be improved and extended in line with WTO guidelines to include partner country information, detailed sector classifications, and information on the operations of foreign affiliates operating through a local commercial presence.More research is needed on how to develop domestic firms’ capabilities, whether through boosting the supply of relevant skillsets, fostering business networks and mutual learning, or encouraging foreign suppliers to transfer expertise by forming joint ventures with local companies. The right approach may well vary by sector.

Join the network

Join the network