Policy Brief

Falling Inequality in Latin America

Policy Changes and Lessons

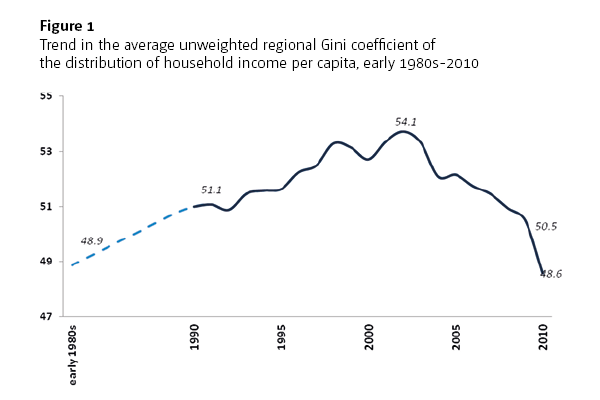

For the last quarter of the twentieth century, Latin America suffered from low growth, rising inequality, and frequent financial crises. However, since the beginning of the twenty-first century the region has enhanced its growth performance, reduced social polarization, and improved macroeconomic stability. The most striking change consisted in a sizeable drop in income inequality benefi tting both the poor and the middle class (Figure 1). The recent Latin American experience thus constitutes an important blueprint for other developing countries moving from authoritarian to democratic regimes, opening up to the market, and emerging from severe crises.

There was a sizeable drop in income inequality benefi tting both the poor and the middle class between 2002–10 in Latin America

The drop in inequality appears to be permanent rather than cyclical, as inequality continued falling during the crisis of 2009–12

An analysis of the data from Chile, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, and Uruguay suggests that the inequality drop was due to: a fall in the skilled–unskilled wage ratio, an increase in social assistance transfers, and a lower concentration of capital incomes

Given the high concentration of land and mining ownership and access to fi nance prevailing in the region, the recent improvements in global economic conditions mainly generated an unequalizing effect on the distribution of market income. Yet, the greater tax buoyancy it triggered allowed the adoption of more progressive public expenditure policies

A key role in the fall of inequality was played by improvements in the distribution of human capital among workers due to a rise in secondary school completion rates, especially among children from poor families

The spread of new policy approaches, due to the regional return to democracy and political shift towards different kinds of left-of-center regimes in the 1990s, was key in the fall of inequality

Trends in income inequality

The high income inequality that has affl icted Latin America for centuries originated from the concentration of land, assets, and political power inherited from the colonial era in the hands of a privileged few. This led to the development of institutions which perpetuated the privileges of this small agrarian, commercial and fi nancial oligarchy well into the 1980s and 1990s.

However, between 2002-10, inequality, as measured by the Gini coeffi cient, fell – to a different extent and with different timing – in nearly all 18 countries analysed, with the exception of Nicaragua and Costa Rica. The unweighted regional Gini coeffi cient, which had risen by 0.32 points a year over the 1980s and 0.16 during the 1990s, fell by 0.50 points a year between 2002–08, 0.47 in 2009, and 1.93 in 2010. As a result, by 2010 the region returned to the pre-liberalization level of inequality of the early 1980s. Such a drop appears to be permanent rather than cyclical, as inequality continued to fall during the crisis of 2009–12. An appreciation of the exceptionality of such an outcome is given by the fact that during the 2000s no other region experienced a generalized and sizeable inequality decline such as that enjoyed by Latin America.

Drivers of the recent inequality decline

Analysis of the changes between the early and late 2000s in the dimensional distribution of household income per capita for Chile, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, and Uruguay suggests that the inequality drop was due to (in broad order of importance): a fall in the skilled-unskilled wage ratio, an increase in social assistance transfers, and a lower concentration of capital incomes. In selected economies a fall of the urban-rural wage gap, and more equally distributed migrant remittances were also important.

Were these statistical changes in inequality due to the endogenous play of market forces, exogenous shocks, or policy interventions?

Global economic conditions and growth acceleration

Many observers have argued that the inequality decline of the 2000s was due to ‘luck’ – i.e. an improvement in the global economic conditions of those years. Clearly, the enhancement of the international terms of trade of the region, increase in capital inflows, and surge of migrant remittances in Central America and the Andean region produced beneficial effects on the balance of payments and growth. Yet, due to the high concentration of land and mining ownership, and access to finance prevailing in the region, the recent improvements in global economic conditions generated, ceteris paribus, an unequalizing effect on the distribution of market income.

However, the mid-2000s boom in exports, remittances, and capital inflows accelerated growth by relaxing the balance of payments constraints. But growth per se is no guarantee of a decline in inequality. The beneficial distributive effects of the recent Latin American growth spurt would not have materialized without the changes in public policies discussed below.

A rapid, equitable, accumulation of human capital

A key role was played by an improvement in the distribution of human capital among households due to a rise in secondary school completion rates, especially amongst the poor. A higher supply of better educated workers generated a decline in the skilled-unskilled wage ratio and led to a more equal distribution of human capital among households. The drop in the skilled-unskilled wage ratio was also due to a fall in the supply of unskilled labour, the upgrading of previously uneducated workers, a drop in the demand for skilled workers, a rise in the demand for unskilled workers, and an increase in minimum wages.

New policy approaches

The spread of new policy approaches was another key factor. In the early 1990s the region experienced a return to democracy and, from the late 1990s, a steady shift in political orientation towards different kinds of left-of-centre regimes.

These political shifts affected inequality through the adoption of various distribution-sensitive policies:

Macroeconomic policies. The new regimes adopted prudent macroeconomic policies which avoided the large budget deficits, debt accumulation, and inflation experienced prevalent in the past. With few exceptions, most countries abandoned the fixed exchange rate pegs and opted for managed regimes aimed at achieving a competitive real exchange rate. Consis-tent with this approach, central banks accumulated large international reserves, reduced foreign debt, and in a few cases (such as Colombia and Argentina) introduced capital controls to neutralize the currency bonanza of the 2000s.

Fiscal and monetary policies. Most countries avoided the traditional pro-cyclical and unequalizing fiscal and monetary biases of the past. Fiscal deficits were typically reduced below one per cent of GDP, and in 2006-07 the region recorded a balanced budget. The authorities also attempted to control the money supply, cut interest rates in periods of stagnation, and expanded lending by public banks in periods of crisis. A far stricter regulation of the financial sector helped to avoid highly disequalizing financial crises. In turn, during the 2000s tax policy re-emphasized the role of income tax, progressive taxation, and revenue collection. As a result, the regional tax/GDP ratio rose by 3.5 points over 2003-08, and fell by only 0.35 points during the 2009 recession. These measures helped improve post-tax income inequality – higher revenue generation permitted the non-inflationary financing of an expanded public expenditure.

Trade and financial policies. The free trade policies of the 1990s were not overturned, but intra-regional trade grew quickly as did trade with the Asian countries. Governments also reduced their dependence on foreign borrowing – the region’s foreign reserves grew sharply, and its gross foreign debt declined from 40 to 20.4 per cent of the regional GDP over 2002–09. These changes were likely to be equalizing as they helped to reduce the vulnerability to macroeconomic shocks.

Labour and social expenditure policies. Labour policies explicitly addressed the problems inherited from the past; i.e. unemployment, job informalization, falling unskilled and minimum wages, declining social security coverage, and weakening of institutions for wage negotiations. Several governments decreed hikes in the minimum wage. In most countries, social expenditure started rising in the 1990s and then accelerated in the early 2000s. Most of this increase concerned social assistance and education, generated positive distributive effects, and appears to have become more progressive over time.

How can the fall in inequality continue?

In several countries, particularly those of Central America, a further improvement in income distribution can be achieved by intensifying the policies described above. In richer countries, such as Argentina and Brazil, further gains in the distribution of disposable income can be obtained by improving the quality and targeting of already high public spending. Besides these measures, it is evident that structural reforms need to be introduced to deal with the deep-seated polarization that still affects the region.

Future declines in inequality may well be blocked by the structural biases of the Latin American economy. If left unadressed persistent inequality in access to land, finance and tertiary education, the lack of an industrial policy, low savings and dependence on foreign capital, and the ‘reprimarization’ of exports and output, can lead to retarding the shift to a long-term sustainable and equitable growth path.

If left unaddressed, the structural biases of the Latin American economy – persistent inequality in access to land, finance, and tertiary education, the lack of an industrial policy, low savings and dependence on foreign capital, and the ‘reprimarization’ of exports and output – may well block future declines in inequality by retarding the shift to a longterm sustainable and equitable growth path.

Join the network

Join the network