Background Note

Hidden sovereign debt in developing countries

A country’s public debt burden is one of its most important macroeconomic indicators, but there is growing recognition that debt statistics are plagued by major limitations and shortcomings. For many countries worldwide, it is remarkably difficult to figure out the public debt level with a satisfactory degree of confidence.

In recent years, the issue of hidden debt—unreported or misreported liabilities—has posed a particularly severe challenge. When official statistics are incomplete or biased, the ability of stakeholders to make informed decisions is undermined, leading to inefficient economic outcomes and elevated crisis risks. This background note draws on recent empirical and theoretical research to summarize what we know about hidden debt. It begins with basic definitions and a simple measurement approach to characterize the magnitudes, characteristics, and costs of hidden debt1. Based on this discussion, we will propose specific policy actions to promote greater transparency on sovereign debt.

Defining and measuring hidden debt

Hidden debt comes in many varieties and forms and researchers have used the term to describe different phenomena. Broadly speaking, hidden debt refers to liabilities that governments do not fully disclose to the public and that are not included in their official records and statistics. This might happen because of simple reporting errors and inadequate institutional capacity but can also be the result of deliberate secrecy. In this background note, we define hidden debt as all forms of government debt that need to be reported but are not reported in a violation of World Bank reporting rules2.

The term hidden debt is also often used in a broader sense to represent important contingent liabilities, for example, unguaranteed private sector liabilities of banks and pension funds that are likely to be taken over by the sovereign in case of distress. It is also sometimes being used to refer to off-balance sheet debts that are explicitly structured to remain outside of government statistics, for example, the liabilities of special purpose vehicles. Our focus here is on a smaller subset of unreported liabilities and our estimates should therefore be considered a lower bound for the overall level of hidden debt in developing countries.

For self-evident reasons, hidden debt is difficult to measure and analyse and has therefore been subject to only limited systematic academic study. In a recent research paper, we provide the first systematic attempt to quantify hidden debt by tracking ex-post upward revisions in a comprehensive new database of the full reporting history of the World Bank’s external debt statistics. Our key measurement idea is simple: When previously unreported debt comes to light, past debt statistics need to be revised in hindsight. Tracking these revisions quantifies previously ‘hidden’ liabilities and therefore allows us to characterize the magnitude, drivers, and timing of hidden debt.

To gain a long-run perspective on debt underreporting, we digitize all past annual editions (‘vintages’) of the World Bank International Debt Statistics and its predecessor publications, including the World Debt Tables (1979–96) and the Global Development Finance reports (1997–2013). The resulting database enables quantification of hidden debt across more than 50 different vintages of data, more than 140 debtor countries, and over hundreds of crises episodes.

How sizeable is hidden debt?

Our analysis reveals that ex-post revisions to debt statistics are frequent, systematically upward biased, and can be very large. This implies that the initial reporting of debt data in the World Bank’s external debt statistics is systematically too low. On average, debt statistics are underreported by 1% of GDP across all countries and years.

We show that this is a remarkably pervasive phenomenon: External debt is underreported in all regions, in almost all income groups, and throughout our sample period going back to the 1970s. Time and again, the numbers initially reported by governments did not fully capture the true indebtedness of the country.

Across all countries and years, we identify a total of 1 trillion USD in hidden sovereign borrowing that is only added to the official debt statistics in hindsight, thereby violating the reporting rules of the World Bank. This amounts to 12% of total external sovereign borrowing in our sample. Underreporting of debt is large and common.

Where is underreporting most severe?

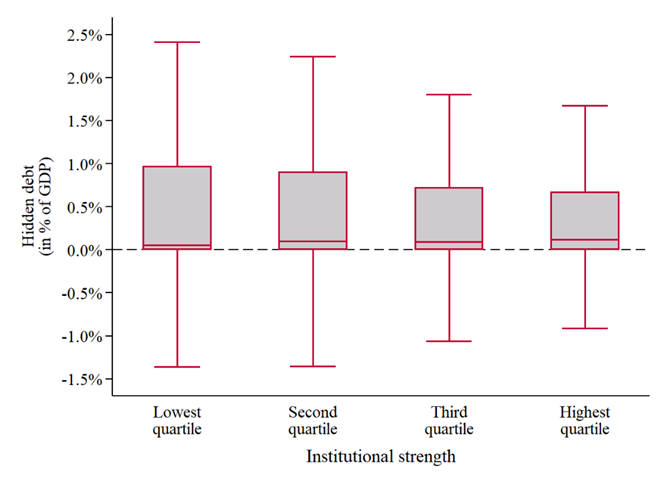

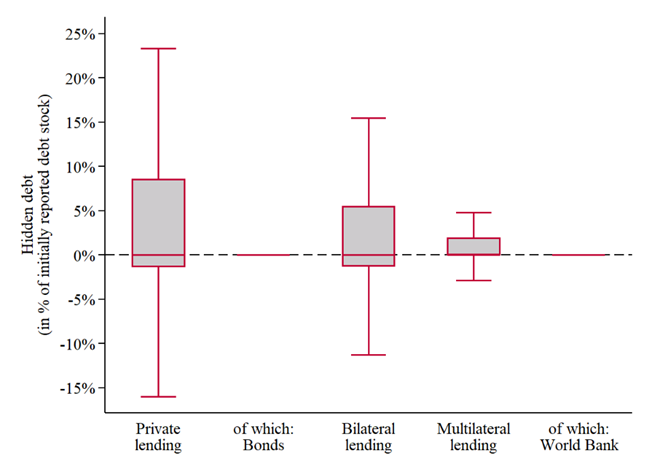

While hidden debt is pervasive across developing and emerging market countries worldwide, we also observe large variation in the degree of underreporting between different groups of countries. This variation allows us to characterize where the hidden debt problem is most severe and where policy initiatives aimed at greater transparency are likely to yield the highest returns. To that end, Figure 1 shows box plots of debt data revisions by different debtor country and creditor groups. The larger the bars, the larger are the data revisions that a group experiences and the greater is the uncertainty about the true debt level. And the more upward skewed the bars, the stronger is the bias of debt statistics to be systematically too low.

Across debtor countries, we find that the key determinant of underreporting is institutional strength (Figure 1, Panel A). Countries with weak capacity, limited checks and balances, and weak rule of law are particularly likely to have their statistics revised and suffer from the strongest underreporting bias. Countries with high institutional capacity show less dispersion, and therefore less uncertainty, but even in this group, reported debt is systematically too low.

Geographically, low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa exhibit the largest underreporting and the most unreliable debt data. The differences between country groups are large: Average underreporting in low-income countries is 1.4% of GDP, compared to only 0.4% of GDP in high-income countries. Consequently, uncertainty about the true value of indebtedness is highest in these countries, representing a potentially very costly impediment to external investment and debt-carrying capacity.

On the creditor side, we find that debts owed to commercial and bilateral creditors are most likely to be revised upward, while revisions for debt owed to bondholders, or the World Bank and the IMF, are rare. This is evident from Panel B of Figure 1: While data revisions are large for commercial bank and bilateral lending, the World Bank data on debt to bondholders and debt to the World Bank itself exhibits hardly any revisions (the box plots are centred at zero)3. This discrepancy confirms that non-marketable instruments, such as those extended by bilateral lenders and commercial banks, are easier to underreport than bonds traded in centralized markets. It may also reflect different lending practices and creditor transparency such as the availability of creditor statistics or the presence and design of confidentiality clauses.

Figure 1: How reliable is external public debt data?

Panel A: Data revisions and the effect of institutional quality

Panel B: Data revisions and the effect of lending practices

Source: authors’ illustrations based on data described in the background note.

When is underreporting most severe?

Our database and measurement approach also allow us to determine the timing of hidden debts and their revelation. We find that hidden debt is highly procyclical. It tends to accumulate during periods of high economic growth and low debt distress risk. In contrast, hidden debts typically surface during economic downturns when governments face low growth and high financial risk. Revelations of hidden debt are especially common during financial crises, IMF loan programmes, or sovereign defaults—events that involve intense scrutiny of a country’s finances and come with large revisions to existing debt data. The average IMF programme, for example, is followed by ex-post upward revisions of 200 million USD in the World Bank’s debt statistics.

The strong cyclicality of hidden debt over the past 50 years suggests that variation in scrutiny and complacency over time is a key determinant of hidden debt build-ups and revelations. During good times, investors and policymakers tend to spend little resources and time on scrutinizing debt data. During crises, however, with investor money and large output losses on the line, concerns about the accuracy of debt statistics take center stage, and large hidden debts often come to light.

This pattern mirrors the procyclicality of capital flows, fiscal policy, and monetary policy in many emerging market and developing countries. Hidden debt amplifies the boom-and-bust cycle by keeping reported debt inaccurately low during the boom and exacerbates downturns by generating additional bad news when countries are already facing high levels of debt distress.

Hidden debt during the latest boom-bust cycle

The past 10 years serve as an instructive example of this empirical pattern. During the 2010s, many developing and emerging market countries experienced large capital inflows, fuelled by low global interest rates, high commodity prices, and low debt levels after the large-scale debt relief initiatives of the early 2000s. In an environment of low debt distress risks and low scrutiny, substantial hidden debt levels built up in various countries in the Global South.

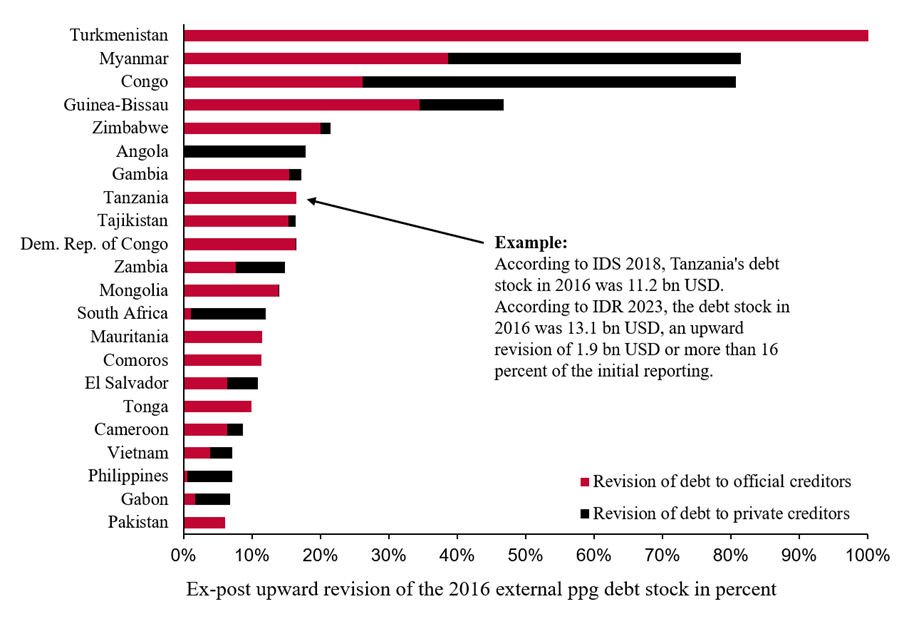

During the COVID-19 pandemic, default risk surged and concerns about hidden debt resurfaced. When international organizations, academics, and investors stepped up their efforts to increase debt transparency, hundreds of billions of dollars in previously unreported loans came to light. Large-scale revisions to the World Bank debt statistics followed and thereby contributed to the fast rise in (documented) external public debt levels. As shown in Figure 2, greater debt transparency dramatically altered the debt levels of dozens of countries, with close to twenty countries experiencing upward revisions of more than 10% of their initially reported debt stocks. In line with past revision patterns (Figure 1), upward revisions were largest in low-income countries with weak institutions and were mainly driven by debt owed to non-bond private and bilateral official creditors.

Figure 2: Debt stock revisions during the pandemic era – top cases

Source: authors’ illustration based on data described in the background note.

The costs of hidden debt

Hidden debt imposes substantial welfare costs. First, it leads to higher borrowing costs as investors will include the uncertainty about a country’s true debt level in their calculus of risk. As a result, the sovereign faces higher risk of debt distress and has lower debt-carrying capacity. This limits a country’s capacity to finance productive investments or to stabilize the economy during adverse shocks.

Hidden debt is particularly detrimental for low-income countries which are subject to notoriously volatile economic cycles and that heavily rely on external capital to meet large investment needs. The large and procyclical underreporting of debt in these countries likely leads to especially large welfare costs by deterring important investments, by raising borrowing costs, and by generating additional economic volatility. In fact, hidden debt can help explain why low-income countries suffer from ‘debt intolerance’ and default at surprisingly low levels of reported external debt.

Moreover, hidden debt complicates crisis resolution efforts. During debt restructurings, creditor cooperation is key. Creditors must come together to negotiate improved financial terms for the sovereign’s external debt and must accept lower returns on the investments they made. Hidden debt undermines these negotiations by eroding trust between creditors and the sovereign. During Zambia’s recent debt restructuring, for example, concerns about hidden debt became a significant obstacle. An empirical analysis of past default episodes confirms that countries with higher hidden debt experience longer restructuring episodes that prolong the social and economic fallout of debt crises.

Solutions

Our new understanding of hidden debts and the dynamics surrounding them has important implications for efforts to increase the transparency of debt markets around the world and particularly in lower income and vulnerable countries. First, the large welfare costs of hidden debt imply that it should be a priority to address the issue. Hidden debt is a large and common and our work suggests that both debtors and creditors have important roles to play in improving the accuracy of debt statics.

On the debtor’s side, institutional quality and statistical capacity are important drivers of hidden debt. While challenging to implement, this finding underscores how important it is to strengthen institutions in order to foster economic development and prevent financial crises. Investments in statistical capacity, stronger IT systems, and regular technical assistance to debt management offices can go a long way in making debt statistics more reliable.

Hidden debt is not solely a capacity issue. Even countries with strong institutions and high statistical capacity underreport, which highlights structural problems and deeply entrenched incentives to obscure borrowing. The hidden debt scandal in Mozambique is a recent prominent example of deliberately secretive and illegal borrowing. Strengthening the role of oversight actors, such as government audit institutions and parliament in overseeing borrowing may help in this regard.

Creditors can also play an important role in addressing underreporting. Lending by commercial banks and bilateral creditors is much more likely to go unreported. Hence these creditors have the most to do to strengthen the transparency of their lending practices. The loan-by-loan public dissemination of creditor statistics as recently initiated by some creditors (though with limited participation) offers a straightforward way to cross-check and validate debtor-reported numbers and strongly limits the scope for sovereigns to hide their liabilities.

Finally, the timing of debt transparency efforts matters. For more than five decades, underreporting issues in emerging market and developing countries have been remarkably procyclical. Efforts to increase debt transparency are often implemented in response to crisis episodes, followed by prolonged periods of complacency in which hidden debt is allowed to rebound. To achieve lasting results and break the cycle of hidden debt accumulation and revelation, transparency efforts must be applied consistently and persistently.

Endnotes

1 The results reported are based on Horn, S., D. Mihalyi, P. Nickol, and C. Sosa-Padilla (2024). ‘Hidden Debt Revelations’. NBER Working Paper 32947. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

2 We focus on violations of World Bank reporting rules for several reasons. First, the World Bank International Debt Statistics are the most commonly used source for developing and emerging market country debt due to its large country and time coverage. All countries with outstanding debt to the World Bank are required to report their debt statistics on an annual basis. The database also has several desirable statistical properties which facilitate our statistical analysis of revision patterns (see our working paper for details).

3 In 2023, low and middle income countries owed around 45% of their external public and publicly guaranteed debt to bondholders, 25% to multilateral creditors, 15% to bilateral creditors, and 10% to commercial banks.

Join the network

Join the network