Blog

How did South Sudan get stuck in a fragility trap?

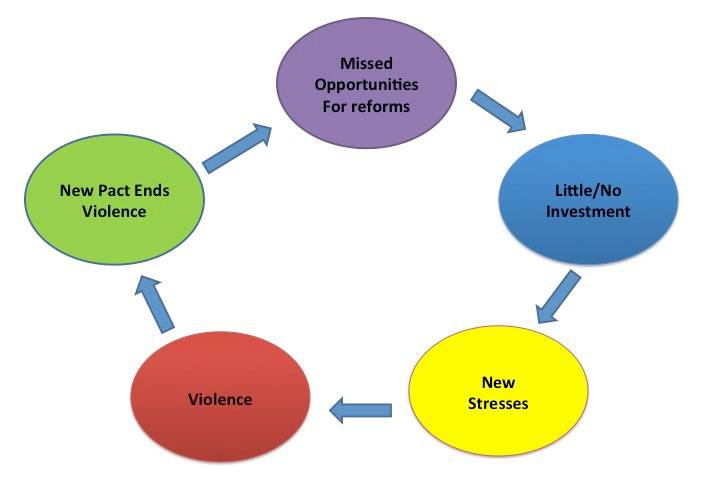

In my last blog I wrote about the common factors at play in political and economic transitions. Using the case of South Sudan, I demonstrated how these factors laid the groundwork for a fragility trap. In this post, I explain what this means.

Trap begins with missed opportunities for reforms

In the above figure of a fragility trap, the first phase (purple circle) is when a country moving out of conflict misses an opportunity to reform its institutions. The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) issued in August 2004 its blueprint, the SPLM Strategic Framework for War-to-Peace Transition, which called for a comprehensive reform. The reform was, however, not implemented as the SPLM strategic framework was shelved after the tragic death of John Garang, Chairman of SPLM and First Vice President of Sudan (9–30 July 2005).

This failure to reform institutions of resistance led to low investment in key areas.

Little or no investment in vital issues

This failure to reform institutions of resistance, in turn, led South Sudan to the second phase (blue circle) of low investment in key areas. There was, for instance, low if not lack of investment in: basic services, social capital, human capital, physical capital, infrastructure, and security sector. Estimates show that the Government of Southern Sudan and Government of the Republic of South Sudan (GRSS) had received a combined estimated amount of US$20 billion of oil revenues during the period 2005-14! Moreover, World Bank records show GRSS had spent US$1.3 billion! But only one highway of 192 km (the Nimule to Juba road) was built with funding from USAID. In fact, that amount of money (i.e. US$1.3 b) could have built 1,300 km of paved roads.

Recklessness and misguided actions create new stresses

Low investment in the key areas, in turn, led to generalized discontent and new stresses, constituting the third phase (yellow circle) of the fragility trap. The stresses were manifested in political recklessness and misguided actions by a number of warlords and militias. Political recklessness was also demonstrated by the SPLM. The two press conferences of 6 and 8 December 2013, in my view, laid the basis for the eruption of the current senseless war in which all the factions of the SPLM have lost.

Violent conflict reoccurs when peace agreements do not address core issues

South Sudan now has the opportunity to exit from the fragility trap if it fully implements the ARCISS.

The fourth phase (red circle) is the eruption of violent conflict, as on 15 December 2013. The fifth phase (green circle) is the peace agreement aimed at ending the violent conflict, which if it fails to address the problem it would lead to the first phase (or purple circle) of missed opportunities to address the root causes of the crisis of governance. This has happened already, the Agreement on Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (ARCISS) was signed on 26 August 2015. It, however, failed to address the underlying causes of the crisis of governance and leadership in the country. And conflict erupted again on 8 July 2016.

It seems, indeed, that South Sudan is stuck in a fragility trap, brought on by the many primary and secondary factors of conflict-induced fragility. South Sudan now has the opportunity to exit from the trap if it fully implements the ARCISS, which is supported by both regional and international development partners.

Background

The title of this blog is a modification of one of the four questions given to me by the organizers of CMI’s panel at the UNU-WIDER Responding to Crises conference in Helsinki in September 2016. After attending all the relevant panels at the event I decided to write this blog.

Lual A Deng is the Managing Director and founder of the Juba-based Ebony Center for Strategic Studies (ECSS).

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network