Background Note

Informal creditors, intercreditor equity, and sovereign debt restructuring

Context

Even before the global negative economic shock resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, a report by the World Bank noted that total developing country debt in 2018 had increased by 54 percentage points of total developing country GDP since 2010.The Institute of International Finance estimated that portfolio outflows (disinvestment in equities and bonds by international investors) from emerging market countries in the initial stages of the pandemic amounted to nearly $100 billion over a period of 45 days starting in late February 2020. In response to the sudden collapse in capital flows, the Rapid Financing Initiative (RFI) was designed to meet the financing needs of several countries at risk of defaulting among emerging market and developing countries: e.g. the quick agreement to provide financial assistance for 77 countries under the RFI (see the COVID-19 Financial Assistance and Debt Service Relief tracker).

Post pandemic, new problems emerged. These include the failure of G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (only Chad, Zambia, and Ethiopia have applied for relief) and the reversal of capital flows from lower and idle income countries in the Global South back to high income countries in the Global North. More lower- and middle-income countries have defaulted, Even those who haven’t defaulted have, in the face of rising bond yields and capital flow reversals, have tried to stave off default by cutting expenditure on health and education and low carbon transitions. In the face of potential insolvency, this slowdown of investment in the SDGs makes their achievement by 2030 unlikely.

The 2022 economic crisis in Sri Lanka is a case in point, a combination of bad policy choices and bad luck. Certainly, the pandemic, the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, and the resulting rise in global commodity prices are all partly to blame and could not have been anticipated. But poor policy choices by a corrupt, authoritarian governing elite also made Sri Lanka uniquely vulnerable. Before 2019, Sri Lanka was self-sufficient in food. The government elected that year banned pesticides, so that only organic farming was allowed, resulting in the shutting of tea plantations (a source of export revenue) and shrinking the country’s ability to feed itself (Sri Lanka now imports grains). Together with the damage to tourism revenues due to the COVID-19 pandemic and rising global commodity prices, tax revenues fell, and pressure mounted on the Sri Lankan rupee.

Public finances were further damaged by unsustainable subsidies and unaffordable tax cuts. On top of this, the government made futile attempts to maintain an unviable currency peg to the US dollar and bad decisions around debt management. Public debt nearly tripled as a percentage of GDP to 104% in three years, while the rupee devalued from about 200 to the US dollar in early March 2022 to almost 330 by the end of April 2022. Political protests by citizens at the sharp end of the fruitless attempts by the government to not default have resulted in deaths and changes of governments between 2022 and the present day.

Sri Lanka’s governing elites are not alone in making these kinds of poor policy choices. For example, in the run up to the crisis that engulfed Lebanon in late 2019, the central bank swapped debt held in Lebanese pounds into debt denominated in euros and US dollars, while maintaining an unviable currency peg. The fees from these activities generated huge profits for major banks but made the country vulnerable to negative external shocks, such as nervous foreign investors dumping government bonds. This helped to drive down the value of the currency and made debts priced in foreign currency harder to pay back.

Just like Sri Lanka, there were protesters on the streets, governing elites waxing eloquently about the need to maintain national unity, and a middle class facing the prospect of being wiped out, while millions were pushed into poverty.

The financial crisis in the eurozone in the 2010s was the result of a similar mix of bad policy choices and bad luck, as was the 1990s Asian financial crisis before it, and the Latin American crisis in the 1980s.

One common thread that cuts across these different episodes is that a sovereign debt crisis is, typically, followed by an international bailout by the IMF and other bodies, in which the money lent (at a positive interest rate, albeit concessional) by the IMF to the debtor state is conditional on reining in the state through severe cuts to public spending, privatizations, and so on. After a gap of a few years, provided the debtor state meets these conditions, borrowing in international capital markets is permitted to resume and the whole cycle repeats itself. There is evidence that such repeated episodes of crises and subsequent austerity could end up diminishing the capacity of the debtor state to govern effectively.

Is there a trade-off between equity and efficiency in sovereign debt restructurings?

The country-specific examples above illustrate that the costs of default are primarily borne by domestic citizens. In contrast, domestic elites, who have access to global financial markets, can mitigate these costs even when ordinary citizens can’t. For example, the total savings of Argentinian citizens in foreign bank accounts equalled the total amount of Argentinian external debt in 2001 when it defaulted. Evidently, the costs associated with sovereign default are unequally distributed within the debtor state. They are also inefficient. The conventional view is that such default costs are necessary to ensure that the debtor state makes policy choices that lower the probability of default in the first place. In doing so, the interest rates at which sovereigns can borrow should become lower (due to lower default risk) leading to ex ante welfare gains as well.

However, as the Argentinian default of 2001 demonstrates, if political power rests in the hands of a domestic elite who can partially insure themselves against the cost of default, then it isn’t clear that costly debt restructuring will lower the probability of default and lead to ex ante welfare gains. Premature capital account liberalization, whereby capital controls are relaxed by lowering the cost of capital flowing in and out of countries, can have the perverse effect of increasing the probability of default (see Ghosal and Miller and Blouin et al.).

The issue of political power over policy choices in the sovereign state continues to be critical even after a sovereign debt restructuring takes place. The probability of a subsequent default is higher unless suitable adjustment policies are put in place. If the costs of debt restructuring are primarily borne by the domestic citizens but decisions about adjustment policies are influenced by domestic elites who are able to insure themselves against the costs of a subsequent debt restructuring, then again, the restructured debt is unlikely to be sustainable.

The Brookings report on sovereign debt restructuring makes a similar point in slightly different language: ‘If the main problem in sovereign debt is not repudiating debtors and overly tight borrowing constraints, but rather over-borrowing at the front end and procrastination at the back end, then the old trade-off between ex-ante and ex-post efficiency no longer holds, at least within some range. Lowering the costs of debt crises ex post might benefit efficiency ex ante’. In a recent report, the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) notes that ‘restructurings are often insufficient […] This lack of a “fresh start” is often the cause of repeated restructuring episodes and may lead to additional costs to all parties’.

In the Brookings report, the complementarity between ex ante and ex post (or interim) efficiency requires the use of a formal sovereign debt bankruptcy procedure. Ghosal and Miller make similar points in the presence of creditor coordination failure—the inability of formal creditors to coordinate on a debt workout- define this term concisely here—and sovereign moral hazard—the likelihood of adopting domestic policies that default more probable rather than less.

A role for informal creditors

Bolton and Skeel and Guzman and Stiglitz highlight the problem of inter-creditor inequity between ‘formal creditors’, such as a West European pension fund buying sovereign bonds, and ‘informal creditors’ within the debtor state itself, such as pensioners who have contributed to the state social security fund, or workers who have paid into the public insurance system, whose claims are based on the social contract between the debtor state and its citizens. Yet in a bailout situation, these informal creditors withstand the worst of austerity, including cuts to social security programmes.

Meanwhile, the formal creditors get their money back—albeit with the possibility of a ‘haircut’ where they lose a proportion of what is owed to them (though such risk is usually already priced into the interest rate at which their money is lent in the first place). Of course, such formal creditors will also include domestic creditors who will be drawn from the elites of the debtor state.

Ghosal and Thomas examine the conditions under which, conditional on an economy-wide negative shock, lowering the costs of sovereign debt restructuring also lowers the interest rate charged ex ante on sovereign debt: these are ex ante and interim efficiency gains. They show, in a simple proof-of-concept theoretical model, that the participation of informal creditors in the decision to restructure debt results in both ex ante and interim efficiency gains, while effectively addressing equity concerns. Their results imply that when informal creditors play a role in debt restructuring:

- Early warning indicators (based on the experience of domestic citizens reliant on government services and payments) of an impending debt crisis become more salient.

- Debt restructuring is more likely to be conducted in a timely fashion after informal creditors conclude that the debtor state is not able to service its existing debt liabilities, and the terms of restructuring (the haircut, changes in the duration of debt servicing) are more likely to restore sustainability.

- Post-debt restructuring will be effective in reducing the need for subsequent debt restructuring.

Policy implications

The impact of a debt crisis on the informal creditors of an insolvent debtor state or countries at risk of default has been the cornerstone of contemporary policy debates on how to resolve sovereign debt crisis. Debtor states typically tend to postpone default even when it faces difficulties in servicing its debt by cutting back on public expenditure (e.g., education or health), reducing its pension liabilities, postponing payment to private contractors engaged in public works. It is only when, in the face of public protests and dwindling foreign exchange reserves that cannot cover essential imports for less than three months or less that debtor states declare default. These policy measures have been characterized by the twin interventions of austerity through welfare cuts to restore debt sustainability and conditionality attached to official sector bailouts have been a consistent feature of the ad hoc system of debt workouts.

In 2015, the UNCTAD published a debt workout roadmap that proposes referendums at key points in the lead-up to a bailout to ensure that the domestic citizens see the options available for debt restructuring and get a chance to vote on them. Our analysis provides guidance for operationalizing such a road map.

In the eurozone crises, the contrasting response of Iceland and Greece to an economy wide negative shock illustrates the very different roles that informal creditors can play in crisis resolution. In the case of Greece, the first referendum was called off in response to market pressures and the second referendum was called to approve a bailout, rather than a debt restructuring. In Iceland, in contrast, the referendum was called to approve the agreed debt restructuring proposal with its formal creditors, and when it wasn’t, the debtor state implemented the results of the referendum. In Greece, informal creditors, ultimately had no input into the terms of the debt restructuring and austerity was imposed on them. In Iceland, no such austerity was experienced by its domestic citizens.

The motivation behind the UNCTAD roadmap was to prevent the recurrence of what has become a common feature of debt crises: the ‘socialization of losses from private debts and the subsequent emergence of sovereign debt crisis in developing and developed countries’. The UNCTAD roadmap aims to enhance ‘coherence, fairness and efficiency of sovereign debt workouts.’ The efficiency deficit identified in the roadmap arises from the problem of restructurings which are ‘too little too late’.

A key aspect of the roadmap is the explicit recognition and acknowledgement of civil society (informal creditors) as an independent constituency whose interests are both distinct from those of the debtor government and the formal creditors. For instance, the principle of impartiality recognizes that debt workouts need to be defined by a ‘neutral perspective particularly, with regard to sustainability assessments and decisions about restructuring terms’ rather than as a procedure to fulfil the self-interest of debtors and creditors.

Further, the issue of ‘sustainability requires that sovereign debt workouts are completed in a timely and efficient manner [...] while minimizing costs for economic and social rights and development in the debtor state’. Here for debt workouts to restore debt sustainability, both ex-ante and interim efficiency must be achieved. This limits the problem of ‘too little too late’ by explicitly accounting for the impact of workouts on informal creditors.

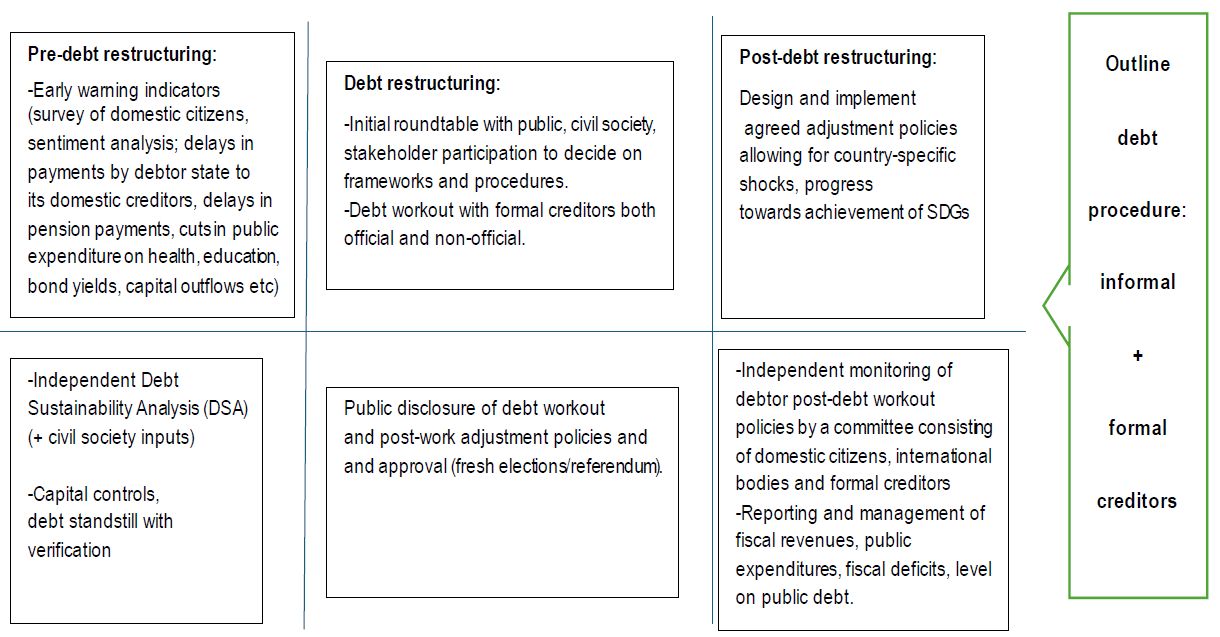

Figure 1: Elements of a sovereign debt restructuring procedure with informal creditor participation

The procedure specifies formal opportunities for inclusion of the non-elite in the decision to restructure debt. Importantly, to be effective, the process by which informal creditors would be consulted in the decision to restructure debt needs to be laid out beforehand.

Giving informal creditors a voice to determine the point at which debt becomes unsustainable and as well as in debt restructuring negotiations mitigates two problems: the problem of delay in recognizing a problem of debt sustainability and the problem of debt workouts being too shallow and requiring repeated official sector involvement in the restoration of debt sustainability through bailouts.

As stated above, debtor states typically tend to postpone default even when it faces difficulties in servicing its debt by cutting back on public expenditure. The impact of such expenditure cuts is initially experienced by domestic citizens living in the debtor state. Figure 1 above illustrates that, in the pre-debt restructuring phase, the day-to-day experience of domestic creditors provide an early warning indicator of the difficulties that the debtor state faces in servicing its existing debt obligations. By involving informal creditors these early warning can be monitored, recognized and once a threshold level has been crossed, an independent debt sustainability analysis can be conducted which, in turn, will initiate a process by which debt is restructured. In this way the problem of delay in recognizing an issue of debt sustainability can be mitigated.

Transparency and representation of informal creditors via elected members in negotiations with official creditors, both formal and informal, will ensure that informal creditors are kept informed and updated about the terms of debt restructuring. A temporary standstill will ensure that domestic citizens aren’t unduly disadvantaged during the negotiations so that essential public expenditure can be maintained. Approval of the terms of debt restructuring via referendum will have two consequences: it will remove the need for protests which can turn violent, prevent the loss of lives, destruction of property, and it will ensure that the terms themselves are acceptable to the domestic citizens of the debtor state (a point that be will at the forefront of the debt negotiations). Given domestic citizens (with the exception of the domestic elite) cannot insure themselves against negative shocks to the domestic economy or the costs of future debt crisis, they have the greatest interest in ensuring that the restructure debt is sustainable. Hence, requiring their approval will ensure that the debt workout is deep enough, and adjustment policies post a debt restructuring are appropriate to ensure the sustainability of the restructured debt.

Conclusion

In the context of the wider debt debate, this note raises, but does not answer the following questions: To what extent should the official creditors and debtors be limited by considerations of equity and fairness to informal creditors, when the need to restore liquidity and prevent debtor insolvency is often the highest priority? Does informal creditor participation at this stage limit the ability of the official sector to intervene to stop a self-fulfilling crisis?

One answer to this question depends on the nature of the crisis that is triggering the intervention. If the intervention is an isolated self-fulfilling liquidity crisis, then there is justifiably a limited role for private sector bail-ins—restructuring debt to private formal creditors via debt rescheduling to ensure that the sovereign debtor is able to re-access global markets quickly for its liquidity needs. On the other hand, as in Sri Lanka or in Lebanon, where the debtor state is insolvent, overlooking and excluding informal creditors cannot be justified.

Another answer to this question depends on the outcome of the process, rather than the nature of the crisis. For example, if the outcome of this official sector intervention is conditionality, imposing an excessive cost on informal creditors, then in addition to the nature of the crisis, finding an outcome in which the costs of the crisis are distributed equitably between informal and formal creditors.

An issue that we haven’t explicitly discussed is whether informal creditors should be involved in the decisions of the debtor state that increase the risk of a debt crisis by socializing risk of private decisions, such the bail out of a collapsing industry or banks. Iceland is a case in point. It is those decisions of the debtor state that lead to debt crisis further down the line. A collapse of banks or a major industry will generate costs that will be experienced by informal creditors (workers, depositors, mortgage holders, small/medium businesses seeking liquidity). Instead of waiting for approval of informal creditors further down the line when a debt restructuring becomes inevitable, it may be even more effective to their involvement at an earlier stage. Examining the points at which involvement of informal creditors could prevent a debt crisis might be more effective than arguing for their involvement in the resolution of a debt crisis.

Join the network

Join the network