Blog

Just transitions and the importance of social protection reforms for ambitious climate action

As greenhouse gases once again climb to record levels, countries are under pressure to make the move to a low-carbon economy. Policies that move in this direction are needed to mitigate against the worst impacts of climate change, but policy choices will have winners and losers.

As it is crucial to consider the effects of climate change mitigation policies on various population groups, we explore two policy options —carbon pricing and removal of fossil fuel subsidies. In our latest microsimulation study, we model the impacts of these climate policies on poverty rates and inequality levels. Our study—conducted jointly by SASPRI, LSE, IDOS, and GIZ—also analyse which social protection reform options are most effective at offsetting the negative impacts for those likely to face downsides in low- and middle-income countries.

What impact do climate change mitigation policies have on poverty and inequality?

Carbon pricing and the removal of fuel subsidies may negatively affect some people and vulnerable groups disproportionately. The main focus of our analysis is on carbon pricing in Ecuador, Indonesia, South Africa, Tanzania, Viet Nam, and Zambia. Carbon pricing is a globally considered mitigation measure with significant direct impacts on the financial situation of households. We also consider the removal of fuel subsidies in Indonesia, South Africa, and Zambia.

Key findings

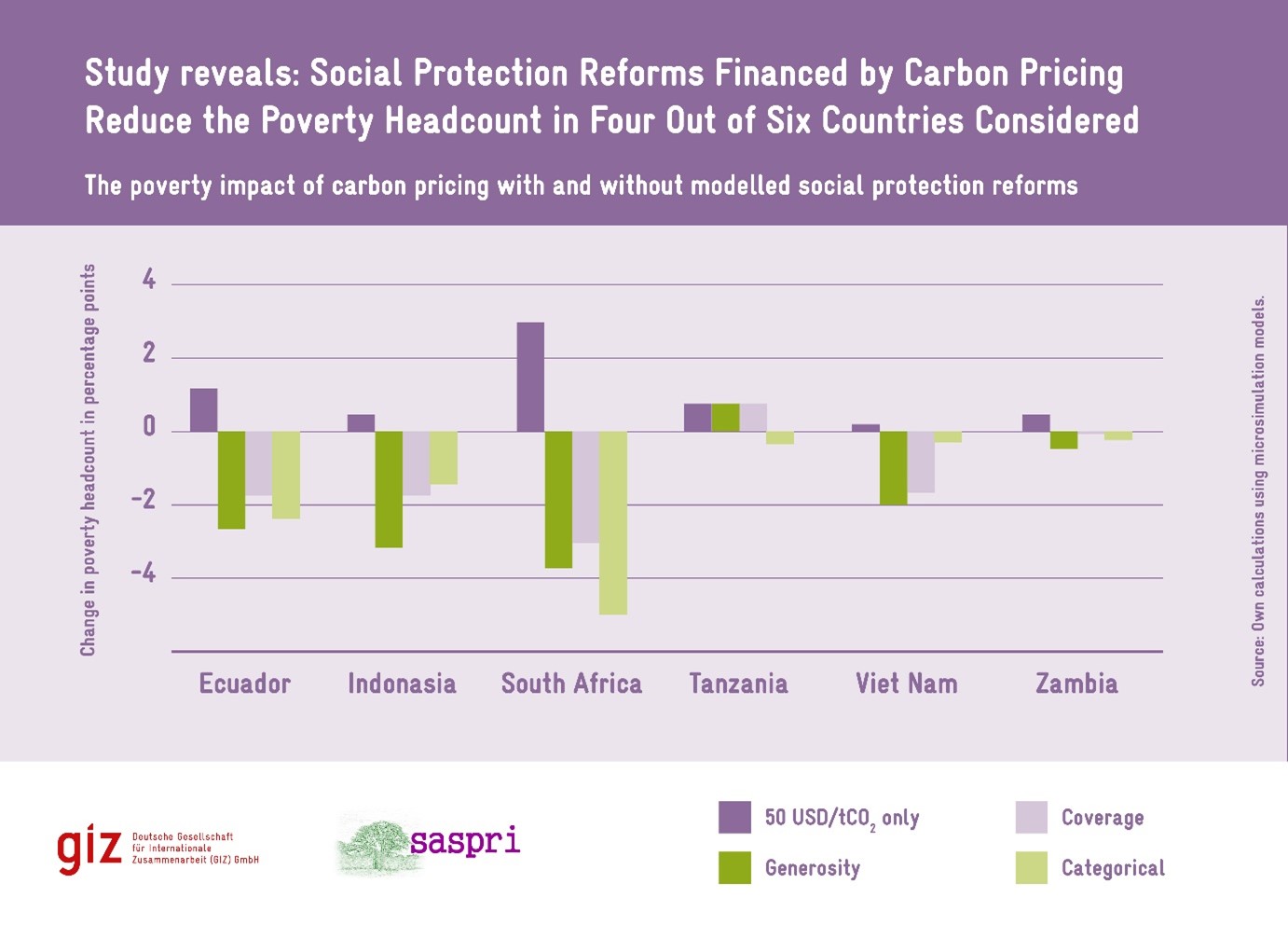

In Ecuador, South Africa, and Viet Nam, model simulations indicate that an introduction of carbon pricing disproportionately disadvantages people in the lower income/consumption quintiles. Compared to even a low carbon tax rate, the removal of fossil fuel subsidies leads to smaller relative changes in household purchasing power (measured as mean consumption), but also affects the poorest quintile the most in both Indonesia and South Africa. In Zambia, better off households feel more of the effects of fuel subsidy removal. This illustrate why social protection will be important to help mitigate againstthe regressive nature of climate policies, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The poverty impact of carbon pricing with and without modelled social protection reforms

Source: Gasior et al. (2024: 30).

Additional revenues from carbon pricing and subsidy removal can be used to expand social protection

Using the SOUTHMOD tax-benefit microsimulation models for Ecuador, Viet Nam, Tanzania, and Zambia, SAMOD for South Africa, and INDOMOD for Indonesia, we assess what would happen if revenue generated by climate policies is used to expand the existing social protection system to target vulnerable populations. We simulate three reform options:

- The ‘generosity’ reform increases the benefit amount/duration of existing schemes (vertical expansion), while covering the same number of programme participants

- The ‘coverage’ reform expands existing schemes to more people (horizontal expansion), with a more moderate increase in benefit amounts

- The ‘categorical’ reform leaves all existing schemes as they are, but adds a new unconditional benefit for select vulnerable groups (children, the elderly, and people of working age with disabilities)

All three reform scenarios cushion the overall drop in mean income/consumption. While they lead to significant income/consumption increases at the bottom of the distribution across countries and reform scenarios, the same effects are not observed towards the top of the distribution.

In four of the six countries (Ecuador, Indonesia, South Africa, and Viet Nam), the modelled social protection reforms not only cushion the shock of carbon pricing, but result in an overall reduction in the poverty headcount. In Tanzania and Zambia, the poverty headcount is not significantly reduced, because the revenue generated is too small to fill the gaps in the current social protection system.

The generosity reform scenario

An increase in benefit amounts leads to a more significant reduction in poverty than an expansion of coverage in Ecuador, Indonesia, Viet Nam, and South Africa.

When poverty is concentrated at the bottom of the distribution, the generosity scenario results in better cushioning effects for those in poverty than the other reforms considered. This is particularly notable in the case of Viet Nam.

However, increasing generosity for those currently covered by social assistance does not necessarily provide the best cushioning effects for those in the lower quintiles because the scale of the impact depends on how well the current social protection system covers those in need.

The coverage reform scenario

Extending social protection coverage to more people can lead to better results for lower-income population groups, i.e., the lower quintiles in the income distribution.

In Zambia in particular, increasing coverage generates a higher relative increase in average incomes for people in the bottom quintile, by reducing coverage gaps in the current social protection system.

The categorical reform scenario

The introduction of a categorical benefit for vulnerable groups has a stabilising effect on income/consumption in most of the countries considered. This comes at the cost of smaller increases in average income/consumption for people in the lower quintiles, compared to the other two reform scenarios (except in South Africa and Ecuador).

Categorical benefits for specific groups are an option for countries where poverty is not solely concentrated at the very bottom of the income/consumption distribution but affects a large proportion of the population, such as Tanzania and Zambia, with potentially easier administration.

Our study highlights that the reform impact notably depends on the following, e.g.:

- The existing poverty situation: In countries with high levels of poverty, the potential for significant poverty reduction is lower. This is because the revenue generated by carbon pricing often only provides limited resources, compared to what is needed to reform existing social protection systems.

- The effectiveness of the existing social protection system: This is true both in terms of existing benefit levels and coverage. The status quo also determines the extent to which existing benefits can/need to be extended or complemented by a new categorical benefit. This means that the shortcomings of existing systems are potentially amplified when introducing climate change mitigation policies.

- The available financing or potential: In addition to existing fiscal space, countries with higher carbon footprints have greater potential for revenue generation through the introduction of carbon pricing (such as South Africa) and are in a better position to reinvest it in improving social protection.

Fiscal space may also be needed to strengthen the functionality of the social protection system, by investing in infrastructure (data and information, delivery mechanisms, physical and staff capacities, etc.).

What are the policy recommendations emerging from the study?

Social protection is a key policy area to complement climate change mitigation and achieve a just transition. Effective social protection systems can enable more ambitious climate action and sustain public support for it. Research shows that climate change mitigation policies are more likely to be supported if the revenue is used to support and protect populations groups (likely to be) affected (Dabla-Norris et al., 2023). Policymakers should understand how the existing social protection system works and what its limitations are to better guide social protection reform(s). Reforms need to consider the current poverty situation, fiscal space, the size of the national carbon footprint, and the current capacity of the existing social protection system.

Social protection policies need to be planned well in advance as part of a just transition package. In this way, social protection can alleviate, or even avoid, the negative socio-economic effects of climate change mitigation policies on, especially, vulnerable people and those already living in poverty. Options at the global level, e.g., a global carbon tax, are likely to have a much stronger impact on poverty reduction than national-level carbon pricing in the Global South.

Learn more about which social protection reforms may be most suitable for your country contexts in the full study.

Christina Dankmeyer is Advisor Just Transition and Social Protection Financing at Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

Katrin Gasior is Senior Research Fellow at Southern African Social Policy Research Insights (SASPRI).

Gemma Wright is co-Executive Director of Southern African Social Policy Research Insights (SASPRI).

The views expressed in this piece are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network