Policy Brief

Measuring quality of health-care services

What is known and where are the knowledge gaps?

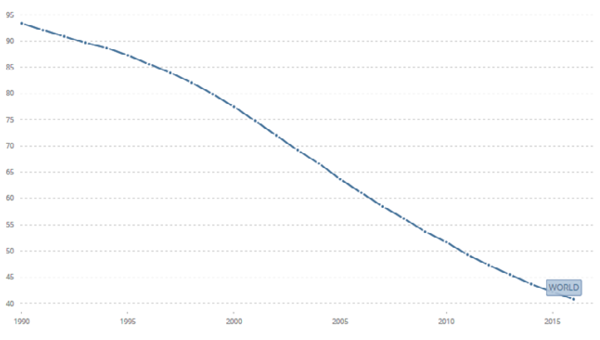

Under the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) remarkably progress has been made on health issues. Globally, under-five mortality rate has decreased by 56%, from an estimated rate of 93 deaths per 1000 live births in 1990 to 41 deaths per 1000 live births in 2016. To build health-care systems that could achieve progress towards the MDGs, many countries had to extend delivery systems to increase coverage.

Quality of antenatal and paediatric care in seven African countries varies greatly and that this variation may result from the different approaches governments take in training providers and funding and organizing their health systems.

In Uttar Pradesh, essential care provided to women and their neonates – during labour and childbirth – was generally of poor quality. The private facilities generally outperformed the public facilities in terms of both obstetric and neonatal care.

In Kyrgyzstan – a setting with high rates of hospitalization, over-diagnosis and over-treatment – brief training and supportive supervision by paediatricians improve quality of paediatric care in hospitals.

With the end of the MDG era, the international community agreed on a new framework – the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG 3 encompasses the benchmarks to achieve Universal Health Care Coverage (UHC) as it seeks ‘to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all and at all ages’. Under this new frame and with the complex services required for noncommunicable diseases, the focus on measuring coverage is not sufficient anymore to capture whether people receive effective care. There is no benefit to UHC if people are unwilling to use financially-covered services due to the poor quality.

With the end of the MDG era, the international community agreed on a new framework – the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG 3 encompasses the benchmarks to achieve Universal Health Care Coverage (UHC) as it seeks ‘to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all and at all ages’. Under this new frame and with the complex services required for noncommunicable diseases, the focus on measuring coverage is not sufficient anymore to capture whether people receive effective care. There is no benefit to UHC if people are unwilling to use financially-covered services due to the poor quality.

Figure 1: Mortality rate, under-5 (per 1000 live births), 1990-2016

Beyond healthcare coverage

UNU-WIDER in partnership with WHO released the Special Journal Issue ‘Measuring quality of care’. The articles within this issue provide a glimpse of current research on quality of health-care services in low- and middle-income countries. Throughout the studies, the authors make a strong case for the need for governments to both improve health-care quality and to be able to measure the effects of such improvements.

UNU-WIDER in partnership with WHO released the Special Journal Issue ‘Measuring quality of care’. The articles within this issue provide a glimpse of current research on quality of health-care services in low- and middle-income countries. Throughout the studies, the authors make a strong case for the need for governments to both improve health-care quality and to be able to measure the effects of such improvements.

A study published in this issue shows that quality of antenatal and paediatric care in seven African countries varies greatly and that this variation may result from the different approaches governments take in training providers as well as funding and organizing their health systems.

Another study from Uttar Pradesh, India, suggests that essential care provided to women and their neonates – during labour and childbirth – was generally of poor quality. The private facilities generally outperformed the public facilities in terms of both obstetric and neonatal care. And in Kyrgyzstan it was found that a brief training and supportive supervision by paediatricians improve quality of paediatric care.

Another study from Uttar Pradesh, India, suggests that essential care provided to women and their neonates – during labour and childbirth – was generally of poor quality. The private facilities generally outperformed the public facilities in terms of both obstetric and neonatal care. And in Kyrgyzstan it was found that a brief training and supportive supervision by paediatricians improve quality of paediatric care.

Next steps

As a next step, quality of care should be integrated into existing policy dialogues. National quality policies and strategies need to reflect the trade-offs between the ability to measure, and the ability to deliver, higher-quality health services. Global indicators for quality, integration and people-centeredness of health services and a framework for measurement in these areas will be proposed to the 2018 World Health Assembly to aid countries in their own monitoring efforts.

The substantial variation in quality of care should prompt examination of national standards for professional education of health-care providers and health-system policies to support quality care

Tailored quality-improvement initiatives must be designed for facilities in the public and private sector – with the regular auditing of the actual processes of care linked to functional accountability mechanisms

Policy-makers should consider using supportive supervision to increase adherence to evidence-based guidelines for paediatric hospital care

At the same time, development partners can contribute to this work by developing and validating measurement standards, data collection tools and supporting evaluation research. Better health is unlikely without better health-care quality, and improving health-care quality demands measurement that is accurate and usable by countries.

Join the network

Join the network