Blog

Peer influence and human capital accumulation

Evidence from Delhi University colleges

College is an important milestone in life that is believed to develop several aspects of an individual's human capital, broadly defined to include both cognitive and socio-emotional traits. Consequently, there is great emphasis on obtaining admission into a more selective college. This column draws upon data from Delhi University to examine the returns to enrolling in a more selective college.

How does admission into a more selective college shape students’ cognitive and non-cognitive aspects of human capital? We know from existing research that academic gains from attending elite education institutions are not uniformly positive (for example, Abdulkadiroğlu et al.2014, Lucas and Mbiti 2014, Pop-Eleches and Urquiola 2013). However, the literature remains largely silent on the underlying behavioural responses that could explain these mixed effects. In Dasgupta, Mani, Sharma and Singhal (2017), we estimate the effects of attending a more selective college on not only academic performance, but also on behavioural and personality traits that are equally important in determining educational attainment, occupational choice, and labour market performance (Almlund et al. 2011).

Elite colleges demand incoming students to score high on entrance examinations that determine admission. Consequently, a student who gets admitted in these colleges is surrounded by high-performing peers, and is expected to gain from a high-quality learning environment, and plausibly be motivated to keep up with the competition due to peer pressure, etc. Hence, the effect of being surrounded by a smarter peer group is expected to be positive. However, the education psychology literature suggests that there could also be negative effects of competitive peer environments on students. Those just above the cutoffs of more selective colleges are in fact also worst-off relative to their peer group (‘small fish in a big pond’) while those just below the cutoff who gain admission to the next best colleges are relatively better than their peers (‘big fish in a small pond’). This lower relative position could result in a detrimental or zero impact on the behaviour and personality of the marginally admitted student. As a result, on the net, for the student who just makes it to a better college, the effects could go either way.

Context

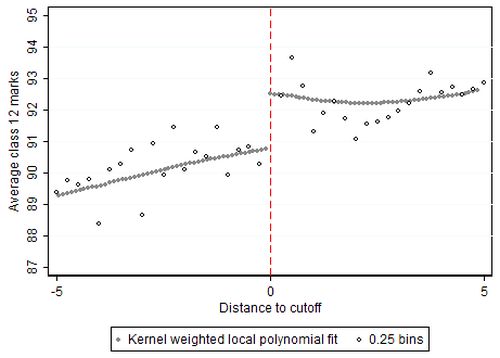

In general, little is known about the effects of college quality in developing country contexts. To that end, we look at admissions to colleges affiliated with the University of Delhi (DU), where students face a highly competitive admission process. For example, in 2017, almost 220,000 students applied for 54,000 undergraduate seats at DU. Admissions to colleges are based on students’ average scores on high school exit examinations. Every June, students apply for college-specific disciplines, and based on the applications received, colleges declare cutoffs such that applicants with scores above the cutoff are eligible for admission. Since there is a greater demand for elite colleges, they are oversubscribed, resulting in their cutoffs being systematically higher than those of low-quality colleges. This of course implies that high-scoring students are likely to attend more selective/higher quality colleges while low-scoring students get admitted to less selective/lower quality colleges. The change in peer ability on crossing the admission threshold is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Change in peer ability

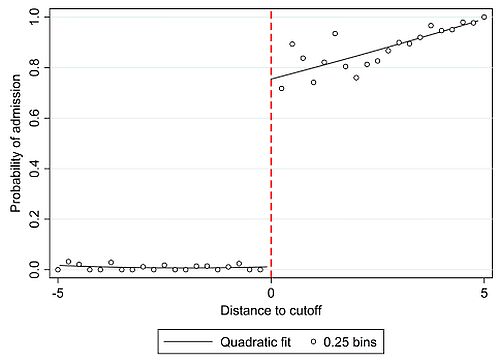

The features of the admission process are crucial for our identification strategy. As applicants cannot manipulate which side of the cutoff they will fall on, we can use a ‘regression discontinuity design’ (RDD) and compare students just above the cutoff to those just below it – who are otherwise similar except for the college environment – to measure the impact of enrolment in a more selective college. Figure 2 shows that there is a jump in the probability of enrolment at the cutoff. However, as the increase is not 100%, we adjust our estimates for this imperfect compliance (Lee and Lemieux 2010).

Figure 2. Probability of admission

We conducted a large survey with over 2,000 students enrolled in economics and commerce honours programmes across 15 colleges in DU. We used incentivised experiments1 to measure preferences related to competitiveness, overconfidence, and risk. In the survey, we collected information on academic performance, a range of socioeconomic characteristics, grit, as well as the ‘Big Five’ personality traits that include conscientiousness, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and emotional stability.

Results

We find that admission to a more selective college increases students’ scores on university examinations. However, this is entirely driven by the effects on females. The marginally admitted female experiences a 3.8% increase on the standardised university examination scores with no corresponding effects on males. On exploring the sources of this effect, we find that females in more selective colleges have higher attendance rates compared to their counterparts in less selective colleges.

Next, we examine if college quality results in changes in student behaviour and the way students view themselves. We find that males in more selective colleges experience declines in conscientiousness and extraversion, indicating that a lower relative rank among peers in a high-quality college may negatively affect their self-concept. This is also reflected in lower attendance compared to their classmates and could potentially explain the null effects on their examination scores. On the other hand, we find that females’ exposure to more able peer environments makes them less overconfident and less risk averse, in effect making them more prudent. Finally, we are also able to show that variation in college quality stems mainly from variation in peer ability with no differences in teacher presence or student-teacher ratios around the cutoff.

Conclusion

In this study, our objective has been to shed light on the role of college quality and peer environment on students’ cognitive attainment, behavioural and personality traits. While females gain academically from more able peer environments, marginally admitted male students experience declines in some facets of personality due to lower self-concept. While our study shows that the effects of selective colleges are not unequivocally positive for the outcomes we consider in the short-run, it is important to bear in mind that in the long-run, elite colleges provide higher wages, access to well-connected alumni networks, and even better marriage prospects (see, for example, Sekhri 2014, Kaufmann et al. 2015).

Note:

- In incentivised games, participants are paid based on the choices they make (Smith 1976).

This article originally appeared on Ideas for India.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network