Research Brief

Perceptions of inequality among young adults in Mozambique

Differences based on gender

A recent study examines how inequality is perceived among young adults in Mozambique and how perceptions of inequality correlate with different demographic characteristics, including gender. It focuses on how young Mozambicans view the disparities between rich and poor people and why. Additionally, it reports the results of examining their attitudes towards different principles underlying inequality comparisons. Here, we report the key findings on differences based on gender.

Among those surveyed, young women agree more with income redistribution compared to their male counterparts

Women tend to think of inequality more in absolute rather than relative terms, but this depends on the context presented

More studies are needed on gender differences in perceptions of inequality and attitudes towards redistribution

The study finds that young women in Mozambique tend to be more supportive of reducing inequalities than their male counterparts, with some evidence that they also have a greater propensity to understand disparity in absolute, rather than relative, terms. These results are based on data from the latest round of the MUVA Urban Youth Survey conducted in the cities of Beira and Maputo in Mozambique, which included a module on inequality.

There were in total 1,193 respondents to the inequality module, with ages ranging between 15 and 33 years old. Close to 54% live in Beira while 46% in Maputo, and about 56% of the respondents are women. Regarding the education level, most respondents have either completed some years or the full First Cycle of secondary school (grades 8–10) or completed either the 11th or both the 11th and 12th grades. Among the respondents, approximately 67% are currently employed.

Women tend to agree more with income redistribution

According to the survey, women tend to agree more with redistribution through tax and expenditures than their male counterparts. 59% of men agree or completely agree with income transfers compared to 71% of women (Figure 1). This also speaks to findings from experimental research which point out that: women are more pro-redistribution than men (see Durante, Putterman and van der Weele, 2014) and they are more inequality-averse in variants of the dictator game (see Andreoni and Vesterlund, 2001; Dickinson and Tiefenthaler, 2002; Selten and Ockenfels, 1998; Dufwenberg and Muren, 2006). Provision of public goods is also found to be higher in matrilineal societies, compared to patrilineal ones (see Andersen et al., 2008).

Figure 1: Opinion on income transfers from the rich to the poor, by gender

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Men report that they are more frequently in contact with people who are a lot richer than they are, but we otherwise find no statistical difference between the answers of female and male respondents in terms of other aspects of inequality. For instance, most respondents agree that income disparities in their neighbourhood are too large and that the government should help poor people more to improve their living standards.

Absolute versus relative understandings of inequality

Inequality comparisons are prominent in the development discourse and in policy debates. They are frequently linked to arguments around redistributive preferences and the fairness of distribution decisions. But there is hardly a consensus around which inequality concepts best define and measure disparities. The frequently used measures imply thinking about inequality in relative terms, but evidence suggests that some individuals perceive inequality in absolute terms.

Moreover, variation in the value judgements that lie beneath the choice between absolute and relative measures has implications for the positions individuals take in critical debates, such as the effects of globalization, and can impact how global development agendas are set.

In order to infer whether respondents think about inequality in relative or absolute terms, they were asked to consider different scenarios comparing income distributions in two villages and to choose which village they consider the most equal. Based on their answers, we can deduce their preferences for relative or absolute measures of inequality.

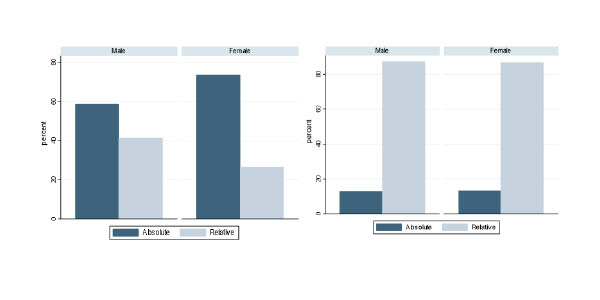

Figure 2: Percentage of Absolute and Relative answers, by gender

Scenario A) Scenario B)

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

If respondents agree with the scale-invariance axiom, implied in relative measures, then they agree that increasing incomes in a proportionate amount leaves inequality unchanged. On the other hand, if respondents agree with the translation-invariance axiom, implied in absolute measures, then they agree that inequality remains the same if we increase incomes by a fixed amount. Even if they are comparing different villages, we can think of the answers in terms of income transformations.

Figure 2 portrays the results of asking individuals to pick which village they think is more equal in the following two scenarios:

Scenario A) Village A: (MZN 1,000; MZN 10,000); Village B: (MZN 2,000; MZN 20,000).

Scenario B) Village A: (MZN 1,000; MZN 10,000); Village B: (MZN 3,000; MZN 12,000).

We can think of scenario A as a transformation where all incomes are doubled and scenario B as a transformation where we add a fixed amount (MZN 2,000) to all incomes. Figure 2a indicates that female respondents seem to have a greater preference for the answer consistent with absolute thinking than male respondents do.

While we found no generalized differences in the answers of female and male respondents, we uncovered some specific points where gender seems to be a relevant factor. This confirms the need to consider the gender dimension when studying inequality and how it is perceived

More studies on perceptions of inequality are needed, not only based on survey data, but also using experimental methods to understand individual behaviour and social preferences

According to the results of an adjusted Wald test, this difference is statistically significant. However, there are no significant differences based on gender when we consider scenario B (Figure 2b) and the link between the answers and gender also disappears when controlling for other sociodemographic characteristics in a probit estimation.

Join the network

Join the network