Background Note

What now for low-income and vulnerable countries’ financing?

What is the issue?

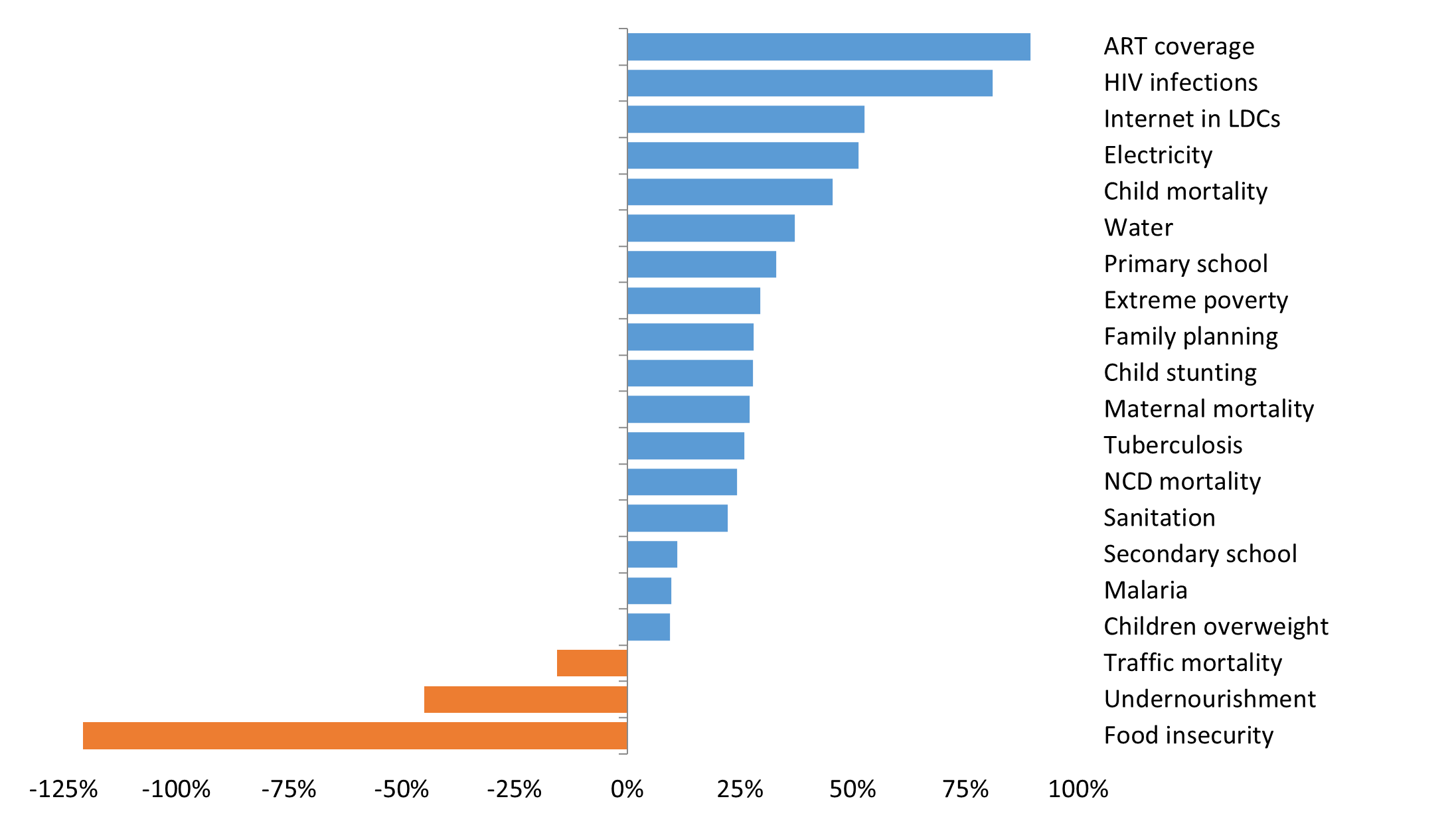

Entering 2025, low-income and vulnerable countries (LIV) are struggling with multidimensional development challenges. LIV countries are defined in this paper to include 77 countries eligible to receive grants or credits from the International Development Association (IDA), the concessional arm of the World Bank Group1. Most critically, economic growth in many LIVs has stalled. Over half of LIV countries have had per capita growth rates below those of advanced economies since 2019. The average annual growth of LIV countries fell from 3.8% (2014–19) to 2.8% (2019–24). Alongside growth, almost all other development targets agreed to in Agenda 2030 are also seriously off-track, in part because of the lack of financial resources to address them in a scalable way (Figure 1 based on Kharas et al. 2024).

Figure 1: Projected progress by LIV countries on SDG targets by 2030 based on current trends

Source: author’s illustration based on underlying data from Kharas et al.

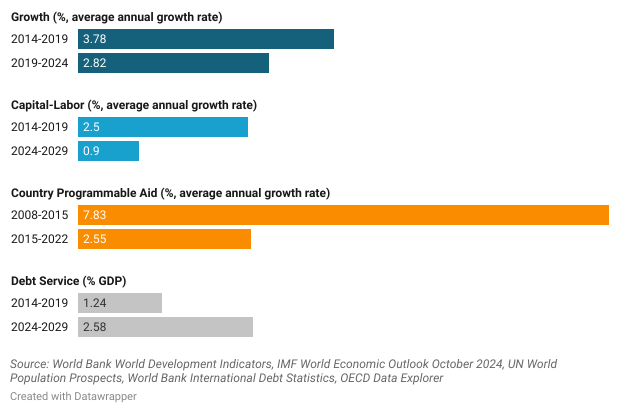

Looking ahead, prospects for meaningful economic transformation are also bleak. LIV countries are experiencing a 2.5% annual increase in their labour force. In the pre-pandemic period of 2014–19, the physical capital stock grew at about double this rate, thanks to an investment rate that exceeded depreciation. But investment cuts have taken the brunt of the macroeconomic adjustment, so the base case projections by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggest a very modest increase in capital-labour ratios, a key metric of the capital intensity of production. The capital-labour ratio grew by less than 1 % per year, between 2024 and 2029, and probably negative in many countries. With investment at such low rates, the transformations that are required—for urbanization, adaptation to climate change, building resilience, protecting nature, and dealing with loss and damage and just transitions—are unlikely.

Part of the problem is a shortage of domestic and external financial resources. In the ten years after the announcement of the Millennium Development Goals in 2000, country programmable aid (CPA)—the portion of official development assistance that is available for development projects within LIVs—rose by 7.7% per year, with significant growth in both bilateral and multilateral CPA. Since the sustainable development goals were agreed upon in 2015, the increase in CPA has been far less generous, growing by only 2.6% per year. Multilateral CPA has continued to grow, but bilateral donors have increasingly cut back their own programmes, to such a degree that their disbursements to LIVs were below 2015 levels in real terms in 2022, the last year for which data is available.

All this has been taking place in a context of tightening global capital markets. The debt service payments of LIV countries are expected to be 66 billion per year on average in 2019 USD or 2.6% of their GDP for 2024–29 USD. This is more than double the 1.2% of GDP they spent in 2014–192. Even though the debt service payments owed by LIVs peaked in 2024, bunched principal repayments and higher-for-longer interest rates will continue to create difficulties for many LIVs in the medium term.

Figure 2 below shows the challenges in summary form.

Figure 2: Economic context for LIV countries: ‘then’ and ‘now’

Prospects for more international aid to address these challenges seem poor. The Secretary-General’s call for an SDG Stimulus Plan of at least USD 500 billion in additional concessional and non-concessional financing for developing countries was met with praise but has yet to mobilize the promised resources. The Plan has three pillars. The first is to ‘tackle the high cost of debt and rising risks of debt distress’. Some progress on speeding up debt resolutions in the context of the Common Framework has been made, and process improvements through dialogue in sovereign debt roundtables continue, but country coverage is low. Only 5 countries are participating in the Common Framework so far, compared to the 31 LIV countries assessed as being in debt distress or having a high risk of debt default according to the IMF’s debt sustainability analysis (DSA) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Comparing debt distress to PPG external debt/GDP for IDA-eligible countries

Source: author’s illustration based on data from IMF World Economic Outlook October 2024, IMF DSA Reports.

The second pillar is to ‘massively scale up affordable long-term financing for development’. The International Development Association (IDA) is the largest organization providing such financing to LIVs. It concluded its 21st replenishment at a scale of USD 100 billion over three years in December 2024. While significant, the contribution of fresh resources from donors, the main element of concessional financing in IDA’s portfolio, is likely to be around USD 24 billion, a small decrease in real terms from the USD 23.5 billion that was pledged for IDA20.

Other efforts to mobilize affordable long-term financing for LIV countries also fall short. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) COP29 meeting at Baku promised USD 300 billion per year for developing countries, but from all sources—including private finance—and for all countries. LIVs are unlikely to get a major share of this funding. The COP16 biodiversity meeting in Cali similarly ended with disappointments on finance—raising pledges for millions, rather than billions, of dollars and in a voluntary, rather than binding, fashion.

The third pillar is to expand contingency financing, a source of credit that can be drawn upon quickly whenever needed. For example, contingency financing is often important in the immediate aftermath of a natural disaster. On-going arrangements to recycle USD 100 billion equivalent of Special Drawing Rights resulted in the creation of a new Resilience and Sustainability Trust at the IMF. In 2024, the IMF disbursed USD 3.4 billion from this Trust—a noteworthy accomplishment but small in comparison to the USD 2.7 trillion of LIV GDP in 2024. The IMF has also put its Poverty Reduction and Growth trust on a stable financial footing which enables sustainable annual lending of some USD 3.6 billion per year, but again this amounts to only 0.1% of LIV GDP.

Given these headwinds the operative question now is what can be done in 2025 and beyond.

What needs to happen?

Entering 2025, development advocates have a stark choice to make. They can continue to make the moral case for more government aid, debt write-downs, and exhortations for voluntary private investment in LIV countries, or they can look for an alternative pathway. The moral case seems doomed to disappoint. It was tried, with maximum civil society pressure, during 2024 at international summits including the Pact for the Future at the UN, the negotiations for the 21st replenishment of IDA, and at the Baku and Cali COP processes. None of these efforts attracted any significant increases in the real dollar value of concessional financing for LIV countries.

All signs indicate that budgetary pressures in advanced economies will limit the political willingness to provide more aid. Indeed, it may be difficult even to retain aid at current levels. The EU’s budget plan predicts at least USD 2 billion in annual cuts. The new US Administration has brought its aid programmes to a halt for at least 90 days pending a review of their alignment with US national interest, issuing an Executive Order on President Trump’s first day in office.

These trends should not be seen as isolated, or as a response to recent political events. Rather they reflect a shift in how ODA is viewed by donors. Outgoing EU Development Commissioner Jutta Urpilainen refers to a post-ODA era where aid is used as a catalyst to attract private investment, including large infrastructure projects funded through the EU’s Global Gateway.

The idea that aid can catalyse private finance on a large scale has not, however, proven to be scalable, despite considerable experimentation, not least from the introduction of the private sector window into IDA18. Flows of private finance to Global South countries have been procyclical, contracting sharply when monetary policy in advanced economies tightens, as happened in 2024. High interest rates, short maturities, and volatility mean that private finance to LIVs must be carefully managed to avoid a debt crisis.

Apart from aid and private finance, the only remaining source of scalable external finance is official non-concessional lending. This is largely absent in LIV countries. The irony is that the same donors that have espoused private finance as the major source of development finance have simultaneously suggested that the risks of non-concessional lending to LIV countries by the official institutions they control are too high to be prudently taken. For decades, there was little multilateral non-concessional lending to LIV countries. Since 2014, that has started to change but the scale remains limited. For example, the largest multilateral lender—the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development IBRD—has avoided lending to LIV blend countries such as Ghana due to its early assessment of Ghana as a high-risk country, even as that country borrowed in private capital markets.

The issue is that the methodology for assessing risk in LIV countries is overly focused on the present value of existing debt—four of the five debt distress indicators used in the IMF-IDA DSA use external public and publicly guaranteed debt and debt service. These indicators are highly sensitive to the level of indebtedness but are not sensitive to the long-term benefits that may arise from the investments financed by debt. What is missing is a ‘a solid basis for a policy dialogue on growth and the public investments needed for development within a sustainable macroeconomic framework’.

This policy dialogue is now coming into sharper focus thanks to the various global conversations of 2024. Among the emerging themes, the following deserve special attention:

- A human development crisis is brewing. Already, UNESCO and Education Ministers from the Global South have revised targets for educational achievement by 2030 downward. Their minimum allocations recommend an increase of at least 0.7 % points of GDP in incremental spending by 2030. In similar vein, the pandemic has made clear that the USD 9 per capita that low-income countries currently spend on health should be increased multiple times to achieve a minimum level of primary health outcomes. These and other studies suggest that the well-documented investment case for human capital is even stronger today than before.

- A clean energy revolution is in the making. Although LIVs contribute little to greenhouse gas emissions, the precipitous drop in the price of solar panels and wind turbines makes these the least cost option for accelerating access to modern electricity for hundreds of millions of people in LIV countries. Demographic growth, economic demand, and a backlog of underserved people and businesses makes clean energy a huge opportunity to invest in inclusive growth, even when the added costs of a just transition are factored in.

- With climate change already wreaking destruction through storms, floods, droughts and other natural disasters, adaptation and resilience activities are a priority. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) assesses the adaptation finance gap at 10–18 times as great as current expenditures. Proportionately, low-income countries have the greatest need for incremental adaptation investments, up to 2 percentage points of GDP. With high estimated returns of up to 6:1, adaptation is a priority. Without additional adaptation spending, the costs to LIV economies of natural disasters will continue to rise.

- Agreement on the Kunming-Montreal global biodiversity framework put the protection of nature at the center of development for all countries. Old-style ‘develop first, clean up later’ models are wasteful as a long-term strategy. With the advent of climate change and the importance of nature-based solutions for adaptation and resilience, the priority of investing in nature has only grown over time.

Taken together, the four areas above constitute a need for a ‘big investment push’ in LIV countries. Without such an investment push, there is a high likelihood of a spiral of stagnant growth, declining capital inflows, and higher risk premia leaving LIV countries vulnerable to natural disasters and other economic shocks. The best way out of this spiral is to invest and re-start growth, supported by long-term non-concessional lending from official international financial institutions.

What next?

Countries face three hurdles in implementing this strategy: (i) a need to change mind-sets to prioritize growth; (ii) a need to develop programmes of transformational change, with bankable investment projects; and (iii) a medium- to long-term financing plan that is consistent with macroeconomic stability and with a big investment push.

The mind-set change

The first hurdle is to change mind-sets towards a new approach that focuses on sustainable development. The core approach was spelled out by US Treasury Undersecretary for International Affairs, Jay Shambaugh:

If you are a country committed to sustainable development and if you are willing to engage with the IMF and MDBs to unlock significant financing alongside significant reform measures, there needs to be a financing package from bilateral, multilateral, and private sector sources to bridge your liquidity needs in a way that is supportive of your sustainable long-run development.

Easier said than done. LIV finance ministers have long been concerned about the effectiveness of public spending and are encouraged by major international financial institutions (IFIs) to keep tight control over fiscal deficits. In some countries, fiscal rules constrain the government’s policy choices on the level of fiscal deficits. The mind-set change that needs to happen is to understand that a borrow-to-invest strategy can be less risky in today’s context than a strategy of fiscal austerity.

Available evidence supports the idea that despite the many distortions evident in LIV countries, the economic rate of return to properly designed investments remains high in most country contexts. Ex post returns on IDA projects, and projects financed by the US Millennium Challenge Corporation and the Asian Development Bank, show double-digit rates of return with project failure rates of less than one in twenty.

Although this microeconomic evidence may not appear to be consistent with the high levels of distress observed in LIV countries, the harsh reality is that public expenditure in LIV countries has tilted towards social assistance programmes, including inefficient subsidies, while public investment levels have lagged badly. The change that is needed is to use new borrowing to finance investment rather than consumption.

Investment programming

The second hurdle is to develop well-prepared policy and investment programmes that can achieve transformative change. There has been a long tradition of programmatic financing of health and education programmes, for example the World Bank’s Global Financing Facility and its support for the Global Partnership for Education. Identifying equivalent programmes in the newer areas of investment priorities is now underway. Among LIV countries, Senegal is leading the way with its Just Energy Transition Partnership programme to increase the share of renewables to 40 % of installed electric generation capacity. Other LIV countries, however, still rely on individual projects often prepared by international institutions. They need to strengthen their capacity to develop country platforms for specific transformational changes that can ensure coherence between development programmes and financial programmes.

The example of Pakistan shows the inconsistencies between diagnosis and programming in the real world. The World Bank’s Country and Climate Development Report for Pakistan identifies an incremental 10% of GDP in desirable annual spending between 2023–30, focused on disaster preparedness, low-carbon power supply, transport decarbonization and water and sanitation. However, Pakistan also has an extended arrangement with the IMF. In this programme, the general government’s primary budget surplus is to be raised to 1% of GDP on average (more when windfall distributions are added), while gross capital formation is projected to shrink in the medium-term, largely due to restricted activities of state-owned enterprises including the energy and water companies. Government investment will remain flat at 2% of GDP if Pakistan continues to meet the IMF’s financing conditions.

Serious plans for transformational change in a country will not be drawn up when the likelihood of adoption is slim—Pakistan does not have a country platform for any sector transformation. The vast gap between the financial programming approach of the IMF and the development programming approach of the World Bank creates a major problem for coherence in country programmes. The contrasting models highlight differences in time horizons. The short-term financial programming model of the IMF has lower risks in the short run but higher risks in the medium to longer term because development vulnerabilities remain unaddressed. The reverse is true for the development programming model.

Neither perspective is satisfactory on its own. They must be jointly considered. However, development programming models are largely confined to the research wings of IFIs rather than to the operational departments of these institutions and hence their practical influence on policies is diminished. Financial programming dominates actual policy discourse.

Financing prospects

Because many of the priority investments identified in a country platform have high long-term development benefits, such as those related to green energy generation, they can be financed with non-concessional loans from official multilateral and bilateral financial institutions, and by the private sector. Official non-concessional financing has the benefit of being readily scalable, especially for LIV countries, thanks to the relatively small size of these economies. Private financing can also be a useful complement, provided it is subjected to the same long-term considerations as official finance and provided the cost of finance is reasonable.

As a first step, many more LIV countries should prepare a priority country platform along with their development partners.

As a second step, the debt service suspension initiative of the G20 should be extended to cover the period from 2025 to 2030. It is likely that only official bilateral debt service would be suspended but this would already provide substantial savings (USD 150 billion) for LIV countries. A rescheduling of this kind should not require any new budgetary requirements from G20 countries.

It is unlikely that either multilateral lenders or the private sector would participate in such a programme. For these lenders, the emphasis should be on new loans to finance the projects identified in qualified country platforms. Multilateral lenders could commit to maintaining or increasing their exposure in qualifying LIV countries, based both on country platforms and on their own country climate and development reports. They should first utilize available concessional finance and then additionally consider non-concessional lending to LIV partners. Their decisions on the volume of non-concessional lending should be based on the pipeline of sound investments and long-term models of debt sustainability, rather than on crude rules-of-thumb, such as remaining below an arbitrary public debt/GDP ratio, as recommended in the current DSA.

Private lenders, too, could be expected to participate in a country platform, especially if such loans were afforded better treatment in possible future debt resolution packages (dubbed the ‘halo effect’ by Standard & Poor’s). Most of the private finance would be expected to be in infrastructure projects, suitable for long-term lenders, rather than general purpose bond finance.

Concluding remarks

Traditional sources of financing for LIV countries are drying up, just at a time when they are faced with a radical new economic landscape. While the challenges of debt distress, post-pandemic economic scarring, and investment cut-backs are major, they have thrown into sharp relief emerging priorities for public and private spending. These include a renewed push on human capital, an opportunity to leapfrog on access to modern electricity, thanks to new low-cost technologies of renewable power generation, an imperative to protect lives and economic assets from climate shocks by strengthening adaptation and resilience, and a vital need to invest in nature, preserve biodiversity, and reverse land degradation.

For LIV countries, the best prospects for accessing new finance for these spending priorities, at scale, would be to advocate for a ‘development’ Debt Service Suspension Initiative3 through 2030 for all official bilateral loans, coupled with relaxed rules on accessing non-concessional multilateral loans for high-return projects identified in granular country platform programming.

Endnotes

1 This grouping contains low-income countries, IDA-eligible and blend lower-middle-income countries and selected vulnerable small island states. See the World Bank Country and Lending Groups for reference.

2 The period 2019–24 is excluded here because of the unique nature of the COVID-19 pandemic that temporarily reduced GDP by significant amounts in some countries.

3 Available here.

Join the network

Join the network