Blog

Why are workers getting a smaller share of the cake in Mexico?

As with many other developed and emerging economies, in recent decades Mexico has experienced a long-term decline in the labour income share. In other words, wages have decreased compared with other sources of income such as capital income. The share of wages in total income has fallen from about 40% in the mid-1970s to around 28% in 2015.

To understand the dynamics behind this trend our research paper takes closer look at the decline for 1990-2015, in both the share of wages in value added and in more comprehensive measures that include the labour income of the self-employed in the informal economy. So, why are workers getting a smaller share of the cake?

Productivity gap between formal and informal economy

According to our study, the decline of the labour income share is largely associated with reductions in the wage share within the formal segment of the economy (work arrangements that are structured, regulated, and paid in a formal way). This implies that the trend is due to real wages consistently lagging behind labour productivity growth in the formal segment of each economic sector (rather than a shift of labour away from informal self-employment into the formal labour).

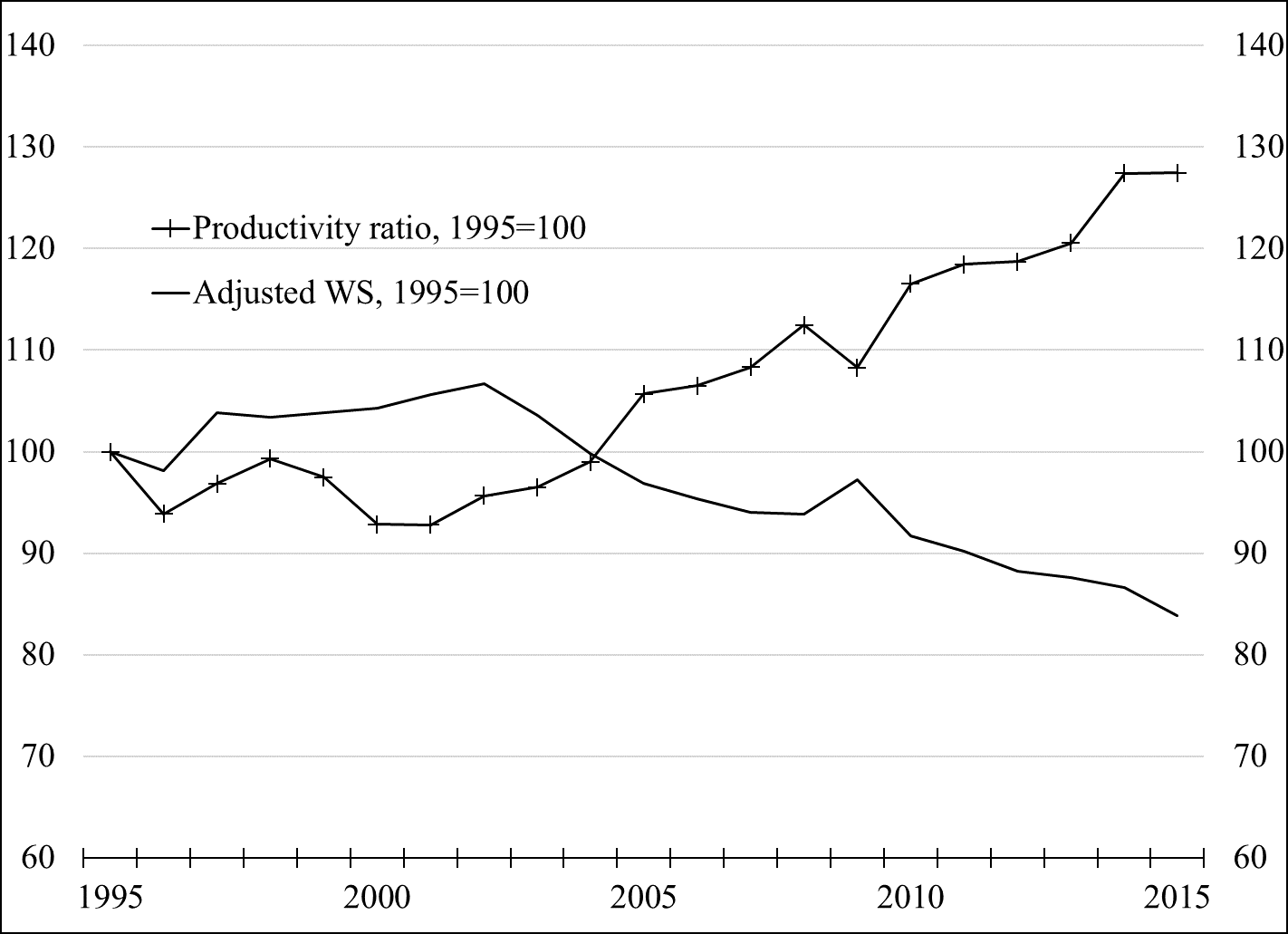

Although institutional factors related to a declining union density and minimum wage policy may have had a role in this development, a crucial factor has been the poor performance of labour productivity in the informal subsectors of the economy. This resulted (especially after 2001) in a steady increase in the productivity differential of formal and informal subsectors of non-tradables (production that can only be performed domestically). When the level of productivity differentiated, but the earnings differential between formal and informal sector did not, the gains in productivity in the formal subsector increased profit margins and reduced the labour income share; see Figure 1. The decline in the wage share in non-tradables put pressure down on the general wage level and contributed also to the fall in the wage share in the manufacturing sector, where real wages fell despite a steady increase in labour productivity.

Figure 1: Productivity ratio and adjusted wage share in non-tradables, 1995–2015

We also show the manufacturing wage share was, in addition, affected by the decline in the share of the labour earnings in the US manufacturing sector from the early 2000s. This may be an indication that trade and technological factors played a role in the fall of the manufacturing wage share.

The paradox of rising profit share but slow growth

Basic economic theory posits that a higher profit share — the portion of income that goes to owners and investors — may accelerate capital accumulation, formalize the informal sectors, and eventually reverse the fall in the labour income share. In this theory a declining rate of informal employment raises productivity in the informal sector with a positive effect on real wages paid by formal subsectors of the economy, which in turn tends to reverse the decline in the wage share in these sectors.

In Mexico, however, this self-correcting mechanism has failed to accelerate growth and reverse the fall in the labour income share. Thus, the country has remained on a low growth path despite the rising profit share.

Domestic and foreign factors behind the paradox

The paradox of slow capital accumulation with a rising profit share may be explained by different factors. There is, first, the role of a depressed domestic market due to the stagnation of real wages. Firms in the tradable sector may avoid the outcome of the stagnation of real wages impacting domestic demand negatively to some extent by shifting from domestic to foreign markets. But this is not possible for the non-tradable sectors which produce for the domestic market and contribute with over 60% of the economy’s total output and employment.

Second, while the profit share has been increasing the overall profit rate has not — particularly in the key manufacturing sector, with one of the sharpest declines in the wage share. The reason is that capital-intensive technological progress has led to increases in the capital-output ratio tending to offset the effects of the increasing profit share on the profit rate.

Finally, relative profitability vis-à-vis the US may have been negatively affected by the simultaneous fall in the US manufacturing labour share. Since the US is the main source of foreign direct investment for Mexico, this may have contributed to the slow rate of capital accumulation in Mexico and constitutes another factor explaining the paradox of slow growth with a rising profit share.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network