Background Note

COVID-19 and socioeconomic impact in Africa

The case of Kenya

The COVID-19 pandemic has now spread to over 180 countries, including several countries in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Kenya reported its first COVID-19 case on 13 March 2020. By 31 March the number of confirmed cases had risen to 59, with over 70 per cent of infections in Nairobi. As at 22 April 2020, the number had quintupled to 303—the highest so far among the East African Community (EAC) member states.2

What has the response been?

Following the first confirmed case, the government moved swiftly to curb the spread of the pandemic. As a starting point, the standard measures of encouraging regular hand washing, social distancing, suspension of public gatherings and events, the closure of learning institutions, and issuance of travel restrictions limiting entry to citizens and foreigners with valid residence permits were instituted.

Government offices and businesses were asked to allow staff to work from home, with the exception of employees working in critical or essential services, and visits to prisons were suspended. Public transport operators were directed to provide hand sanitizer and carry fewer passengers. Other measures included provision of hand-washing facilities in public places and regular disinfection of public and high-risk areas.

These measures have been undertaken on an incremental basis. For example, as the number of confirmed cases increased, the suspension of public gatherings was extended to churches, mosques, and other religious gatherings. When it became apparent that self-quarantine measures were being violated, the government directed all persons entering the country to be quarantined at government-designated facilities before finally suspending all international passenger flights effective 25 March 2020. To strengthen social distancing guidelines, all bars and restaurants were directed to close, except for takeaway service.

The measures were expanded again on 27 March to include a country-wide curfew from 19:00 to 05:00, excepting only critical and essential service providers. Furthermore, the wearing of face masks in public places was made mandatory and the government began recruiting additional health workers to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

Following the closure of borders, the virus is likely to spread through intracommunity transmission. As more people travel from urban to rural home areas, the virus has begun to spread to rural areas where a majority of the elderly live and healthcare facilities are limited.3 Consequently, the government has also imposed a temporary ban on movement in and out of the Nairobi metropolitan area and the most affected counties,4 except for transportation of food supplies and other cargo.

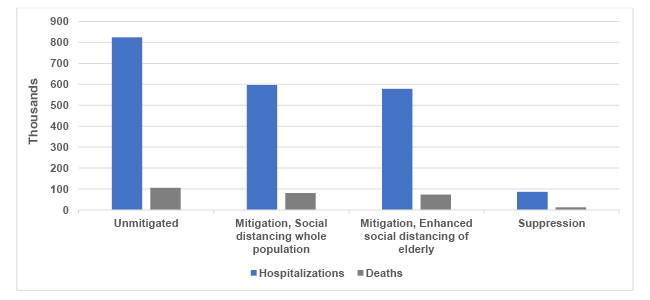

As is clear from Figure 1, there is a compelling rationale for mitigation and suppression measures in Kenya. According to the epidemiological modelling of the global impact of COVID-19, if nothing was done it has been estimated that 824,000 individuals could be hospitalized and 105,000 could die.5 The same projections estimate that mild mitigation measures (reducing social contact rates by 45 per cent and by 60 per cent for the elderly) would reduce deaths to 80,000 and 73,000 respectively.

A broader suppression strategy, equivalent to a national lockdown, which reduces interpersonal contact rates by 75 per cent, would reduce deaths to 12,000. Though there are limitations to the precision of epidemiological modelling, these projections suggest that the suppression strategies of the Kenyan government are saving lives.

Figure 1: Projected hospitalizations and deaths under different mitigation and suppression measures

What are the economic implications of these measures on the poor and most vulnerable?

A month after the detection of first case, the economic impact of the pandemic is already being felt. In March 2020, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) lowered its 2020 growth forecast from 6.2 per cent to 3.4 per cent. Among the key sectors most strongly affected are aviation, hospitality, tourism, and horticulture. Generally, the export sector, is likely to be adversely affected.

The closure of borders has affected trade, including disruptions to the steady supply of staple foods from Uganda and Tanzania. The effects of the pandemic have strained an agriculture sector which was already suffering from locust invasion, raising concerns of food shortages, particularly maize, which is Kenya’s staple.

Economy-wide, workers in the informal sector, casual labourers, and daily-wage earners in the formal sector will be hardest hit. The majority of working Kenyans are employed in the informal sector, which is likely to be the most affected. The sector accounted for 83.6 per cent of the total employment created in 2018.6 These workers include the self-employed and the poor who rely on informal business activities for survival. A significant share of the latter are women.7

Increased rates of unemployment and hopelessness also tend to increase crime. A spike in domestic and gender-based violence is already being witnessed.

The poor and the vulnerable bear the brunt of the negative consequences of both the pandemic and the measures to mitigate its spread. Moreover, economically vulnerable households face a higher risk of contracting the virus—due to crowding and lack of access to basic facilities—and are more at risk of losing access to basic needs. The policy measures so far outlined (see supporting measures below), although helpful, have not fully addressed the more serious impacts on the lowest-income households in Kenya, which are in dire need of support.

Most families in low-income areas, informal settlements, and remote areas lack access to basic public utilities such as water and sanitation. Nearly 80 per cent of Kenyan households have no place for hand washing in or near the toilet.8 As food production and supply are disrupted, the prices of staples could creep upwards, with implications on both the cost of living, and health and nutrition.

People seem more worried about putting food on the table than COVID-19. A street trader recently told a journalist, ‘It is not the coronavirus that will kill us, but hunger!’.

Given the delicate balance between containing the virus and ensuring continuity of socioeconomic activities, social distancing has been perhaps the most difficult measure to enforce and continues to pose a challenge, particularly due to high population densities—especially in Nairobi and Mombasa and in low-income and slum settlements—and the heavy reliance of Kenyan citizens on outdoor informal small-scale business activities.

In Kenya, the first day of the curfew was marked by clashes between the police and members of the public, and tensions between the latter and law enforcement continue to be reported. Without sufficient provisions for food and other necessities for the poor and unemployed, successful enforcement of a total lockdown is an immense challenge in Africa.

But with the number of confirmed cases going up, the government has been under pressure to impose a total lockdown. A total lockdown, however, could escalate shortages of basic food items, encourage hoarding, drive up prices, and heighten social stress.

In the absence of public benefits akin to those in developed countries and proper mechanisms to ensure food and other basic necessities are available to those in need, lockdown and suppression measures have far more devasting impacts—especially on poor and vulnerable groups. However, the need to provide these benefits will create, in turn, a dire need for fiscal space, as Kenya was already facing budgetary constraints.

What supporting measures (fiscal policy, income support measures, etc.) has government taken?

Various fiscal and monetary policy response measures have been outlined to protect incomes and cushion the economy. On 25 March 2020, the President announced a fiscal stimulus package consisting of the following measures:

- 100 per cent relief for persons earning gross monthly income of up to KES24,000.

- Reduction of income tax rate (Pay-As-You-Earn) from 30 per cent to 25 per cent and resident income tax (corporation tax) from 30 per cent to 25 per cent.

- Reduction of the turnover tax rate from 3 per cent to 1 per cent for all micro, small, and medium enterprises.

- Appropriation of an additional KES10 billion to the elderly, orphans, and other vulnerable members of society through cash transfers by the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection.

- Reduction of the value-added tax (VAT) from 16 per cent to 14 per cent effective 1 April 2020.

The President also issued the following directives: payment of at least of KES13 billion of the verified pending bills and all verified VAT refund claims amounting to KES10 billion, or in the alternative, allow for offsetting of withholding VAT, in order to improve cash flows for businesses, and a voluntary reduction in the salaries of the senior ranks of the National Executive.9 The President called on other arms of government to make similar voluntary reductions to help free up revenue.

In addition, a COVID 19 Emergency Response Fund has been created and the National Treasury was directed to utilize KES2 billion of recovered corruption proceeds and reallocate the travel budgets of state agencies to support the most vulnerable. The latest additional measures include presidential directives to develop a welfare package for healthcare professionals, an allocation of KES5 billion to support county governments, inauguration of a weekly support stipend to households in Nairobi,10 and release of KES500 million that were in arrears to persons with severe disabilities.

With regard to monetary policy measures, the CBK lowered the central bank rate (CBR) from 8.25 per cent to 7.25 per cent and the cash reserve ratio (CRR) from 5.25 per cent to 4.25 per cent. Through the latter, additional liquidity of KES35 billion was made available to commercial banks to directly support borrowers. In addition, the CBK extended the maximum tenor of repurchase agreements (REPOs) from 28 to 91 days to allow flexibility on liquidity management.11

The CBK further announced a set of emergency measures to facilitate increased use of mobile money transactions, to curb the spread of the virus through cash handling, by waiving charges for mobile transactions up to Ksh.1,000 and increasing transaction and daily limits for mobile transactions.

Finally, the CBK revised the minimum threshold for submitting negative credit information on borrowers and delisted borrowers previously blacklisted for loans of less than KES1,000 to increase access to credit for those in need.

What more needs to be done to protect the poor and vulnerable?

COVID-19 is a major challenge across Africa, given resource constraints, limited facilities, and fragile health systems. Both short- and long-term measures are needed to address the serious impacts of the pandemic.

In the short-run, budgetary reallocations towards critical sectors and the provision of safety nets to the most vulnerable are most needed. These, together with other resource mobilization initiatives such as the COVID-19 Emergency Response Fund will make a difference. However, there is need for a clear framework and modalities for identifying those with the greatest need. Solutions and resource mobilization should go beyond government initiatives to include non-governmental organizations, the business community, philanthropists, multilateral institutions, and the international community.

Every crisis provides opportunities. There is a need for policies to decongest urban areas and broaden access to the imperative role of technology in ensuring the society continues to function amidst social distancing requirements and travel bans. Other online opportunities include e-commerce, e-learning, and teleworking. Expanding access to the internet, in particular, will continue to be critical going forward. Investment in the health sector to effectively deal with pandemics is also crucial.

In the long term, African countries like Kenya ought to think of strategies for re-engineering the economy and minimizing the impact of future shocks on poor and vulnerable groups.

It is time to provide more incentives to supply local needs through local production and innovation. There is already an on-going initiative to produce masks and personal protective equipment locally. This idea can be expanded for other essential products and will boost supply chains and local industries to sustain jobs. In addition, the country should take advantage of lower international oil prices to increase strategic oil stocks and lower domestic fuel and energy prices.

With the public debt burden weighing heavily on the government, there is need to restructure the debt. A moratorium on debt servicing and debt cancellation by key creditor nations would free up resources and provide the budgetary flexibility needed. International support and aid are needed more than ever to complement local efforts. It is time for the world to act humanely and show solidarity with the most affected.

Join the network

Join the network