WIDER Annual Lecture 25

Women’s struggle for land in South Asia

Can legal reforms trump social norms?

Almost a century has passed since women in South Asia first raised a demand for equal rights in property, especially land, the single most important productive resource in most developing economies. Over time, the struggle broadened and diversified. Despite resistance from conservative lawmakers, this led to notable legal reforms. As a result, the vast majority of Indian women today enjoy legal equality with men in inheritance rights. In neighbouring Nepal, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, women's legal rights in family property have increased greatly, albeit not yet equal to men’s in the latter two countries. However, has this changed ground reality? Have legal reforms helped bridge the gender gap in land ownership? Have they trumped restrictive social norms? If not, are there other ways forward?

In the 1930s, newly formed national women’s organizations in undivided India, which was then under British colonial rule, raised women’s rights in property as a key demand, partly for their own sake and partly because the right to vote and to stand for elections was linked to owning property.

As Forbes (1981) reported: Throughout the 1930s, the women’s organisations formed committees on [women’s] legal status, studied the law, spoke to lawyers, published pamphlets on women’s position, and encouraged various [pieces of] legislation to enhance women’s status. (Forbes 1981: 71)

Supported by liberal male legislators, these efforts bore some fruit initially, for both Hindu and Muslim women, with an increase in the rights of Hindu widows under the Hindu Women’s Right to Property Act of 1937 and an increase in the rights of all Muslim women with the passing of the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act of 1937. Subsequent pre-Independence reforms covered only Hindu women, starting with the drafting of the Hindu Code Bill in 1942 which, among other things, sought to enhance the inheritance rights of daughters.

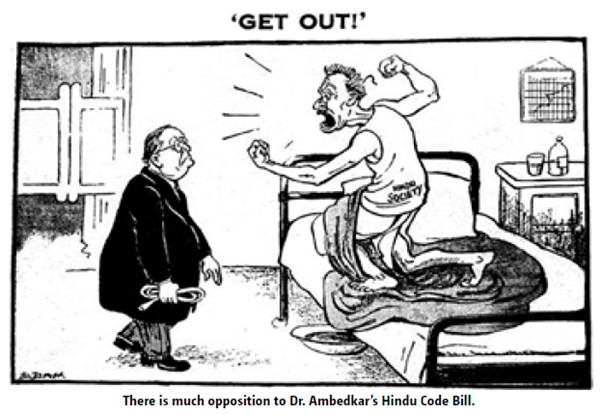

The Bill was, however, subject to heated debates when introduced in the Constituent Assembly of Independent India in 1948, and received mixed responses from male legislators. For example, during the Constituent Assembly and Parliamentary debates in the late 1940s and early 1950s, one Congress legislator asked: Are you going to enact a code which will facilitate the breaking up of our households? (GoI 1949: 1011). Another argued that giving property shares to daughters would spell nothing but disaster;. Yet another legislator said that if daughters inherited property, they would choose not to marry at all, crying out: ‘May God save us from ... having an army of unmarried women; (GoI 1951: 2530). Newspapers had a field day carrying cartoons playing this up.

In the end, following delays and compromises (Agarwal 1994), the progressives prevailed, especially Dr B.R. Ambedkar, a major figure in the drafting of India’s Constitution, and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister. The Hindu Code Bill was split into four separate Acts.1 The Act relating to inheritance was passed as the Hindu Succession Act (HSA) of 1956. Although still gender unequal, it shifted women’s property rights from a position of gross inequality to a fair degree of equality for over 80 per cent of Indian women.

What was the shift? Overall we need to bear in mind that inheritance systems in South Asia are extremely complex: they vary by religion, region, and type of property, with agricultural land being treated differently from other types of property. The Hindu inheritance law had particular complexities: most Hindus fell under the purview of the twelfth century Mitakshara system, which distinguished between a man’s separate property (self-acquired) and his joint family property (ancestral property held as coparcenary shares). Prior to the HSA 1956, the vast majority of Hindu women could only inherit their father’s (or husband’s) property in the absence of four generations of agnatic males. The 1956 Act gave widows and daughters equal shares with sons in a man’s separate property intestate, but only sons had rights by birth in joint family property. And agricultural land was subject to state-level tenurial laws which specified the actual order of inheritance in in six states –Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu, and Kashmir, Delhi, and Uttar Pradesh– all located in northwest India (Agarwal 1995). This specification was highly gender unequal and was applicable to all religious communities.

Join the network

Join the network