Blog

Indonesia, the developer’s dilemma, and Vision 2045

According to the World Bank, Indonesia has reached the upper-middle income status in 2019 after spending almost two decades in the lower-middle income country group. Despite the setback of COVID-19 the Indonesian government aspires to become a ‘developed’ country by 2045, when the country will commemorate 100 years of independence.

However, the economy’s performance over the last two decades —with growth at around 5% per annum— suggests this target will be difficult to achieve. The severe impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic make the goal seem even more daunting. Indonesian GDP shrunk 2.2% in 2020, the worst figure on record since the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis.

Indonesia’s development planners consider structural transformation to be vital for achieving higher economic growth. The country’s official development plan, the Indonesia 2045 Vision, aims to increase the share of industry in GDP from 22.5% in 2016 to 32% in 2045. At the same time, the government plans to build an inclusive society with low poverty rates and low consumption inequality.

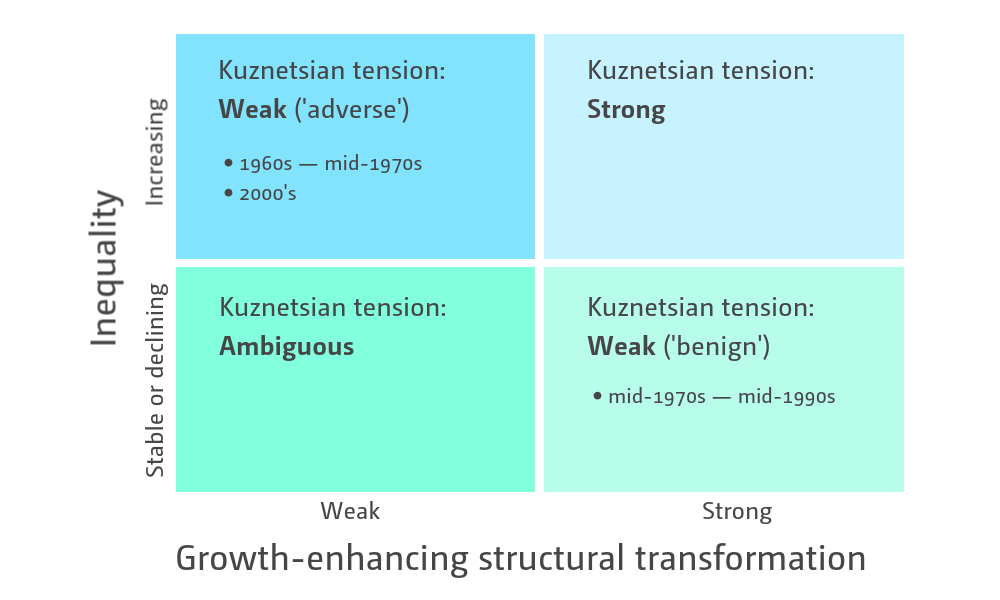

Growth-enhancing structural transformation, or the shift of labour from lower-productivity to higher-productivity activities, is the key mechanism through which developing countries can accelerate economic growth and escape the middle-income trap. Early development economists, such as Simon Kuznets, predicted that structural transformation increases consumption inequality, so that policymakers face what we call ‘the developers’ dilemma’.

It was all going so well…

Before the Asian financial crisis, Indonesia was hailed as one of the eight high-performing Asian ‘miracle’ economies. Between the mid-1970s and the mid-1990s, Indonesia’s growth-enhancing structural transformation was dynamic, with manufacturing driving both productivity and employment growth.

During this period, the poverty rate declined significantly, and consumption inequality declined or remained stable. Our WIDER Working Paper (now a chapter in The developer's dilemma) finds that the Kuznetsian tension —the tension between structural transformation and inequality— was weak in Indonesia at this time. The country showed that economic development can have a strong effect on improved living standards across the population.

However, despite its progress, Indonesia was facing twin challenges of stagnant growth in the manufacturing share and high consumption inequality over the past two decades. Growth-enhancing structural transformation lost its dynamism and overall economic growth slowed. Also, consumption inequality increased significantly until the early-2010s, cancelling out much of the progress Indonesia had achieved in the previous two decades. Today, consumption inequality remains high.

Figure 1: Kuznetsian tension by period, Indonesia|

Service-centred industries are slowing structural transformation

The service sector’s rapid growth in terms of output and employment is a positive trend that contributed to structural transformation since the late 1990s. Yet, the main driver of structural transformation has been non-business services, including transportation, government services, and the trade sector, which predominantly includes small-scale business services that operate informally. These service sectors have labour productivity levels that are lower than that of the overall economy. This trend partly explains why Indonesia’s ‘growth-enhancing’ structural transformation shrank in this more recent period.

Looking at the overall picture, our research finds that none of the economic sectors with above-average labour productivity (such as manufacturing) increased relative productivity and employment shares simultaneously. If this trend continues, it will be difficult for Indonesia to follow in the footsteps of the region’s high-income countries.

However, while a service-centred structural transformation phase has coincided with a rise in inequality, there is no evidence to suggest that the power of economic growth to reduce poverty weakened. This is due in part to the expansion of social protection programmes such as conditional cash transfers and health insurance for the poor. While this is good news for those at risk of falling into extreme poverty, poverty rates at higher thresholds (e.g., US$5.50 at Purchasing Power Parity) have been stubbornly high. If medium-paced economic growth and high inequality continue, further poverty reduction will be much more challenging.

The developer’s dilemma in Indonesia’s policymaking

Escape from the middle-income trap via structural transformation is achievable if Indonesia can restore the growth drivers that boost productivity and employment, like in the mid-1970s and the mid-1990s.

China’s current shift towards ‘advanced industrialization’, which relies on capital-intensive as opposed to labour-intensive manufacturing sectors, may offer Indonesia an opportunity. Southeast Asian economies which have recently experienced ‘stalled industrialization’ —including Indonesia— , may attract some of the labour-intensive manufacturing companies and factories that currently reside in China and are looking for new, more cost-efficient, production bases.

This presents a tempting opportunity, but it will require a well-designed strategy to join the global value chain. Policymakers should remember that the effects of joining global value chains on sustainable economic growth and inclusive development are ambiguous. Therefore, a priority should be to actively negotiate terms with global companies that focus on strengthening developmental benefits. Further, the long-term goal of attracting global companies should be to improve domestic technological capacity.

On top of adapting to the evolution of the global economic environment, the Indonesian government must deal with the developer’s dilemma on the domestic policymaking front. Over the past decade, the government has taken a more proactive approach to economic and social challenges. But government revenue and expenditure, as a share of GDP, is still among the lowest of large developing countries. This causes tension, for example during state budget negotiations, when the administration is pulled in different directions by stakeholders that emphasise different policy areas.

As state activism is likely to continue, tensions are expected between the goal of stimulating structural transformation and the goal of reducing consumption inequality. The only way to quell this is with substantial policy changes to expand fiscal resources and improve inter-bureaucracy coordination. Indonesia’s democratic administration will also need to invest time and energy into legitimising its policy decisions and persuading diverse stakeholders in the policy process to come together.

Arief Anshory Yusuf is Professor of Economics at the Department of Economics, Padjadjaran University, Indonesia, Research Affiliates at Department of International Development of King’s College London, and Honorary Senior Lecturer at Crawford School of Public Policy of the Australian National University.

Kyunghoon Kim is an Associate Research Fellow at the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy (KIEP) and a Research Associate at Department of International Development of King’s College London.

They are contributing authors to the UNU-WIDER book, 'The Developer's Dilemma — Structural Transformation, Inequality Dynamics, and Inclusive Growth'.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network