Blog

New estimates of the cost of ending poverty

What does it mean and how much would it cost?

In a new UNU-WIDER paper, which provides background for this year’s OECD Development Cooperation Report, we take a closer look at the end of poverty, what it really means, what it would cost, and how a new approach can improve the tailoring of development cooperation to different contexts.

To end extreme poverty and absolute monetary poverty worldwide by 2030, it would cost about $70 and $325 billion per year. This may sound like a lot but is only 0.1% and 0.6% of the gross national income (GNI) of the OECD’s high-income countries (HICs). This is lower than the commitments made by OECD countries to deliver 0.7% of GNI in development cooperation finance per annum.

If OECD member countries delivered on their commitments—0.7% of GNI or $425 billion in 2023—there would be sufficient global funds, in principle, to end poverty imminently with funds to spare for the logistical costs of cash transfer schemes.

Granted, our estimates are a minimum cost, as there would be other costs—such as administration and logistics expenses–to deliver transfers to households in poverty. Further, in the medium term it is productive employment that is needed and economic development for all countries in the Global South.

Our estimates of the monetary value of transfers needed to end poverty translates to an annual cost of about $100 per year per person living in extreme monetary poverty and slightly more than $180 per year per person living in absolute monetary poverty. This is the current dollar cost to achieve the major poverty-related global goals and would enable 700 million people to escape conditions of extreme poverty or almost 2 billion to escape absolute poverty (including those in extreme poverty).

Does ending poverty mean ending poverty?

That said, ending global poverty is often equated with ending extreme monetary poverty. For example, SDG 1 to ‘end poverty in all its forms everywhere’ is measured, in target 1.1, indicator 1.1.1, using extreme monetary poverty.

SDG 1, target 1.2 is potentially even less ambitious in the sense that indicators 1.2.1 and 1.2.2 aim to reduce by 50% poverty measured using the national poverty line and multidimensional poverty (according to national definitions), respectively.

Even then there is a difference between whether ending extreme poverty equates to zero extreme poverty or not. The World Bank’s goal to end extreme poverty differs from the UN SDG target 1.1 in that the World Bank’s goal is to reduce extreme poverty to less than 3% of the global population, which would amount to 250 million people still in extreme poverty in 2030 even if achieved.

Additionally, there are non-monetary dimensions of poverty, which can be assessed individually or aggregated in the global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI).

Critiques of the extreme monetary poverty line are widespread and long standing. Specifically, most of the world’s extreme poor do not live in the poorest countries, whose poverty lines are the basis of the $2.15 line. Instead, the majority live in lower-middle income countries (LMICs), where the $3.65 poverty line is the average poverty line of those countries.

Further, it is not clear if having an income of $2.15 per day is sufficient to ensure access to basic health care and basic education and good quality nutrition. In fact, if we consider the number of people in poverty across LICs and MICs, the correlations between headcounts for monetary poverty (ranging from $2.15, every 10 cents, up to $10 per day) and basic education, health and nutrition and access to water and sanitation (using the UNDP/OPHI Multidimensional Poverty Indicator) are stronger at the $3.65 line than at the $2.15 line. This means a better definition for ending poverty is probably the $3.65 per day line. Ending poverty at this line, while still achievable, would inevitably cost more.

Relatedly, countries that have successfully reduced extreme poverty, and may even end extreme poverty by 2030, have surprisingly high levels of non-monetary poverty. For example, in a set of Southeast Asian countries with extreme poverty rates at or below 10%, childhood stunting remains stubbornly high. UNSTATS SDG data shows that about 1 in 3 children under five years old are stunted in Indonesia, 1 in 4 in the Philippines and 1 in 5 in Malaysia even though these countries are projected to end extreme monetary poverty by 2030. In short, ending extreme monetary poverty might not be enough to end child stunting.

There is also an issue of hypersensitivity in estimates. Millions of people globally live barely above the $2.15 and $3.65 lines and remain at risk of falling into poverty. This clustering around the poverty lines underlines how hypersensitive estimates of global poverty are to the precise value of the poverty line used. In fact, the global poverty count increases on average by around 150 million people for every 20 cents added to the value of the line. So, another billion or so people live above the extreme poverty line but under the absolute poverty line of $3.65 a day. In other words, even if extreme poverty were ended it is plausible that more than a billion people could live in absolute monetary poverty.

Where is the cost located?

It is oft noted that global poverty is increasingly focused within sub-Saharan Africa and in fragile and conflict-affected states (FCAS).

That is true. Extreme poverty accounted for by FCAS is forecasted to continue to increase from the current levels of about 45% of global extreme monetary poverty to approaching 60% in 2030.

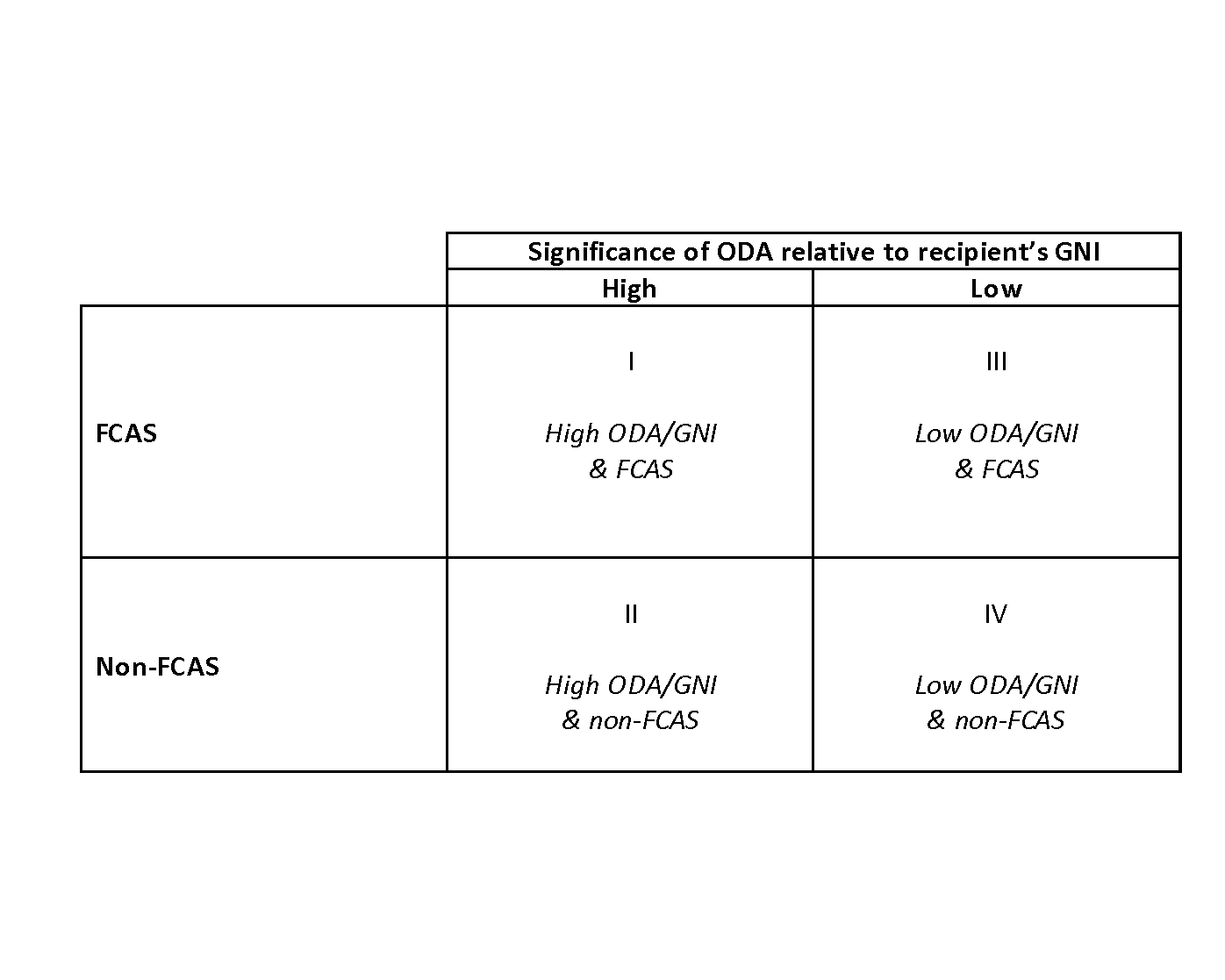

There is another aspect that should receive more attention, due to its importance to development cooperation. This is the distribution of global poverty across countries where ODA is financially significant relative to domestic resources and countries where it is not. This is driven by domestic resources replacing official development assistance (ODA) in significance as economies grow. Beyond the distinction between FCAS and non-FCAS contexts, this is an important differentiation, that between countries where ODA is essential for the government to function well and countries where ODA is now less important.

Different types of country contexts for development cooperation

Source: Author's elaboration

That yields four different contexts to tailor to for development cooperation. Traditional ODA caters to 2 of 4—where ODA is significant, home to only half of the extreme poor and a third of those in absolute poverty. The remaining half of global extreme poverty, of multidimensional poverty, two thirds of the world’s absolute poverty, and almost 85% of the population of LICs and MICs is situated in countries where ODA is less significant, in the sense that its share of GNI is less than the median of the dataset used (thus a relative measure).

So what? What are the implications for development cooperation?

We propose three.

First, ending poverty needs to mean ending more than extreme monetary poverty. Most importantly, if extreme monetary poverty was ended by 2030, a billion or so people would probably live just above that line and still live in absolute poverty.

Second, more tailoring of development cooperation partnerships and the typology can help. Half of global extreme monetary poverty and two thirds of global absolute monetary poverty are accounted for by countries where ODA is low as a share of GNI. Substantial amounts of extreme and absolute poverty remain in countries that are not FCAS or where ODA is less important or even not important at all. An implication for development cooperation is that policy coherence—trade policy, action on tax havens, and so forth—is as important to ending global poverty as ODA is.

Third, the global costs of ending extreme and absolute poverty are not prohibitive, even in fiscally constrained times. Annual ODA spending amounted to $224 billion in 2023, of which $31 billion went to donor countries to address refugee costs, leaving $193 billion allocated to foreign aid. So, the cost of ending extreme monetary poverty annually is about one third of the current annual global ODA spend. And global ODA is equivalent to 60% of the cost of ending absolute poverty.

Of course it is not that simple. Getting the funds to those living in poverty can be incredibly difficult logistically and administratively. However, these estimates do point to the fact that the necessary funds to end global extreme monetary poverty and 60% of absolute monetary poverty are already available.

On the other hand, if OECD member countries delivered on their commitments—0.7% of GNI or $425 billion in 2023—there would be sufficient global funds in principle to end poverty imminently through cash transfer schemes.

Andy Sumner is Professor of International Development at King’s College London and a non-resident senior research fellow at UNU-WIDER.

Arief Anshory Yusuf is Professor of Economics at the Department of Economics, Padjadjaran University, Indonesia a non-resident senior research fellow at UNU-WIDER.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network