Blog

Pay inequality is high in South Africa

Bosses are part of the problem

South Africa is one of the most unequal countries in the world. This income inequality is mostly due to high unemployment and large differences in wages.

In South Africa today, economists and policymakers typically focus on worker characteristics such as education to address wage inequality. Elsewhere, however, attention has recently returned to the power that bosses have to set the wages of workers.

In my study, I document that employer wage-setting explains over a third of wage inequality in South Africa. In fact, for most workers, specific employers explain about half of the differences in pay.

Employers get this power to set wages from a combination of two things. One is the large differences in productivity between employers. The other is the lack of competition —between bosses— for workers, which is likely related to high unemployment. Both factors are particularly severe in South Africa.

As my paper shows, South Africa’s world-leading wage inequality has as much to do with what bosses are doing as it does with how educated or experienced workers are.

Job hopping

A challenge for the paper was to isolate the part of the wage that’s due to employers, and not due to worker characteristics such as education or experience.

One way to do this is to see how a worker’s wage changes when they move from one employer to another. These wage changes cannot be about productivity or skills —it’s the same person being paid a different wage depending only on where they work.

Have you ever moved jobs and received a salary bump, even though you are doing roughly the same work? Economists call this an employer wage premium. Using tax data from 2011 to 2016, I tracked nearly all formal sector job movers in South Africa to estimate this premium for every employer.

In a competitive labour market where bosses do not have the power to set wages, a worker should be paid similarly no matter where they go, and there should be no employer wage premium.

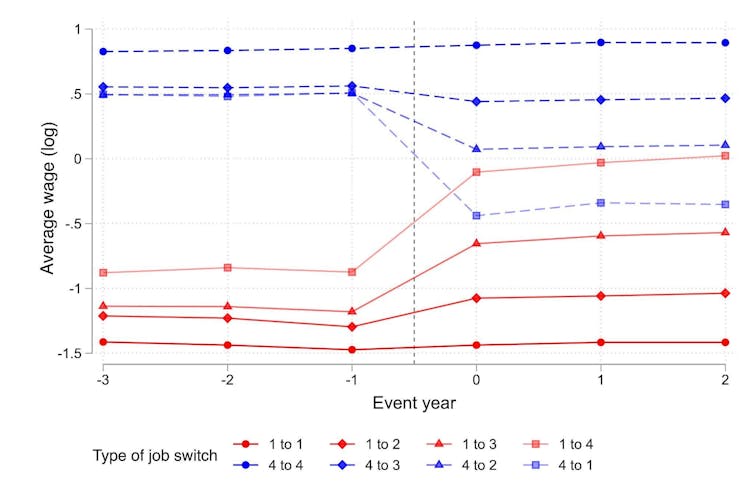

Yet, Figure 1 shows that salary bumps —and drops— after moving jobs can be enormous. A worker lucky enough to move from a low-wage to high-wage employer more than doubles their wage (light red line). The opposite may also happen: a worker at a high-wage job may be forced to move to a low-wage employer, and get paid much less (light blue line).

Figure 1: Wages over time of workers who switch to a new firm

These differences between low- and high-wage employers drive up wage inequality. Altogether, I estimate that employers account for 36% of wage inequality in the formal sector.

Accounting for other sources of inequality (for example, the fact that some people have jobs and others do not), employer wage premiums account for roughly one fifth of overall income inequality in South Africa today.

The boss is a big factor

Much of the discussion on inequality in South Africa is about access to high quality education. This is important. But my research shows that a large part of inequality is also due to which specific employer you land at.

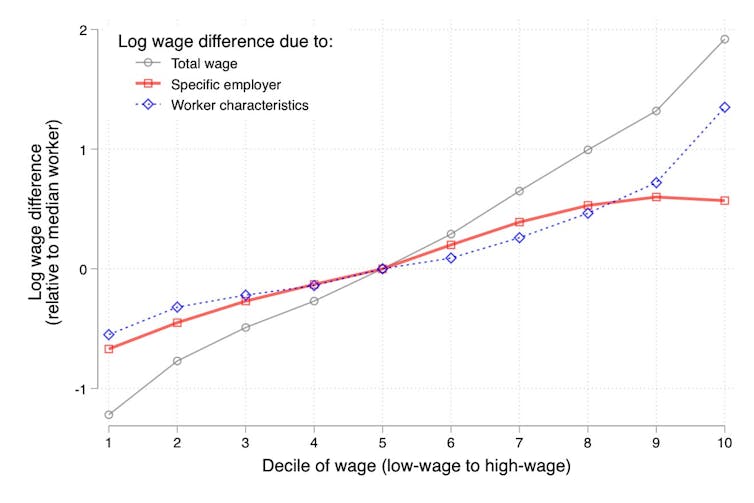

In Figure 2, the difference in total wages for all except the highest paid workers is as much explained by differences in specific employers (red) as differences due to worker characteristics (blue). The upshot is that large parts of workers’ wages have little to do with education.

Such differences in wages due to the specific employer are found in many other countries too. But South Africa stands out for just how much inequality employers account for, at least compared to estimates for richer countries.

Figure 2: Components of income due to worker characteristics and employers, by income decile

Why do bosses increase wage inequality so much?

The leading economic models explaining differences in wages due to specific employers focus on employer productivity dispersion and monopsony power. Monopsony power is when bosses face little competition from other bosses for the labour they employ.

The amount of money you make for an employer, or revenue productivity, depends on many things that are specific to that employer. For example, they may have better technology or have a popular brand. Employers with higher productivity generally pay workers more, and so bigger differences in revenue productivity across employers induce greater wage inequality.

This dispersion in revenue productivity is large in South Africa compared to estimates for richer countries, but is similar to other developing countries like India and China.

However, such revenue productivity dispersion only matters for wage inequality insofar as employers have monopsony power. Without some monopsony power, workers would just quit to the highest paying employer. Indeed, one way to measure this power is to see how much employers can lower wages without workers quitting.

My estimates suggest that there is more monopsony power in South Africa than other places. Bosses pay workers a smaller portion of what is produced, thereby contributing more to the high wage inequality in South Africa. This also means workers face a higher rate of exploitation.

This high employer monopsony power may be due to South Africa’s high unemployment. When unemployment is high, it is more difficult to find a job, and so workers are more reluctant to quit in response to an employer wage cut. This has long been popularly understood in terms of the Marxian 'reserve army of labour'. Thus employers potentially link two of the country’s most devastating features: inequality and unemployment.

Implications for policy

Policy prescriptions to reduce employer monopsony power are complicated. Nevertheless, it should be clear that the contribution of employers to South Africa’s inequality crisis warrants attention. There are potentially large benefits to wages, employment and even taxation.

My analysis reinforces the need to centre the power of bosses over workers in economic analysis.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Ihsaan Bassier is a Researcher in Economics at the London School of Economics and Political Science and at the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit at the University of Cape Town. Access to the SARS tax data used in this article was granted through the SA-TIED programme, a joint initiative between the National Treasury of South Africa and UNU-WIDER. He also received funding and support from the the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies at Wits University. Follow him on Twitter @ihsaanbassier.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network