Blog

The richer your neighbours, the more you borrow – the case of South Africa

Research on how income inequality affects borrowing behaviour reignited after the 2008 global recession. One prevailing theory is that rising income inequality in the US and other high-income economies eroded real household incomes and prompted more and more borrowing. This growing debt culminated in a credit bubble, financial crisis, and eventual recession.

In the broader literature on income inequality and household borrowing, researchers found that households with lower incomes tend to borrow more if their neighbours have higher incomes. However, these studies have been confined predominantly to advanced economies. Hence, little is known about how these relationships operate in Global South economies where poorer households tend to face greater credit constraints and limits on borrowing.

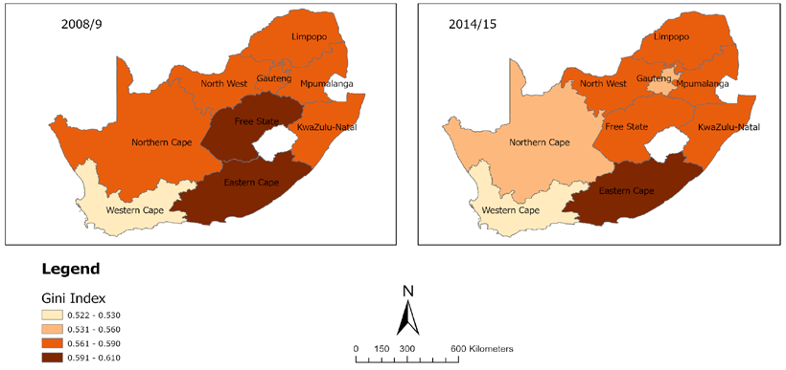

My recent WIDER Working Paper focuses on South Africa—the most unequal country in the world by income. I compare each household to richer households within the same province and estimate how these comparisons influence household debt levels. While income inequality is high in all provinces, the extent of this inequality varies across provinces and over time.

Figure 1: Income inequality across South Africa's provinces

Source: author’s calculations based on the South Africa Living Conditions Survey. ‘Income Inequality And Household Debt: Examining The Impact Of Relative Income On Formal And Informal Debt In South Africa’. WIDER Working Paper 2023/37.

Formal vs. informal borrowing

My study documents two important findings. Firstly, when compared solely by country-wide absolute income levels, richer or higher income households borrow more overall and source more of their debt from formal financial institutions. This implies greater access to formal credit for richer households.

However, when households are compared only against the richer households within their provinces, it is those with lower relative incomes than their neighbours who borrow more. But, they source most of this debt from informal lenders.

This result is consistent with evidence from more advanced economies which suggests that households’ consumption and borrowing behaviour depends on their relative standing in the income distribution. It also highlights a component of borrowing which is distinct to developing economies—the prevalence of informal debt.

A third key finding is that borrowing by those households with lower relative incomes is not spent on large investment goods, such as houses and cars.

These results suggest that households with lower relative incomes may borrow for conspicuous consumption—the purchase of status goods, such as luxury brands—to keep up with their richer neighbours. But, on the other hand, the lowest income households may be using debt, particularly informal debt, to buy necessary goods such as food, or to invest in small-scale businesses.

Do households borrow to keep up with their richer neighbours?

The living conditions surveys which track household’s economic well-being in South Africa do not ask what households use borrowed funds to do. Thus, researchers cannot directly identify whether households with lower relative incomes are borrowing more to ‘keep up with the Joneses’ or to invest in themselves and their futures, or for basic consumption needs.

Nonetheless, a few key observations emerge when examining the type of informal debt that households take up, which I complement with qualitative literature on borrowing in South Africa to draw some preliminary conclusions.

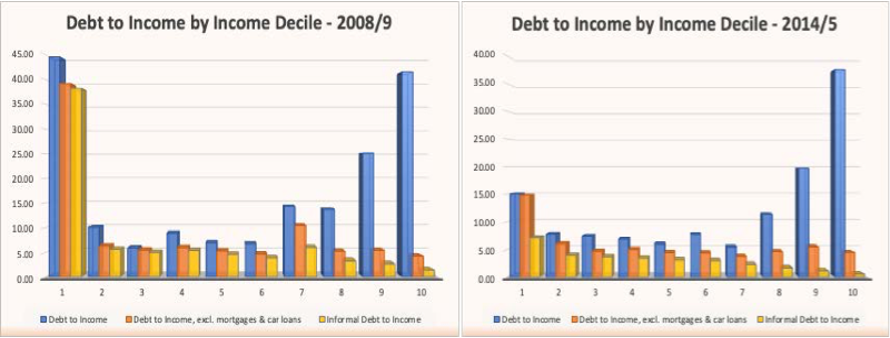

Figure 2: Debt-to-income by income decile

Source: author’s calculations based on the South Africa Living Conditions Survey. ‘Income Inequality And Household Debt: Examining The Impact Of Relative Income On Formal And Informal Debt In South Africa’. WIDER Working Paper 2023/37.

Figure 2 shows average percentages of overall and informal debt-to-income for households at each income decile. Here we see that informal debt (represented by the yellow bars) is highest among poorer households and decreases in importance as we move up the income distribution.

Figure 3 then shows the different informal sources from which this borrowing comes.

Figure 3: Types of informal debt by income decile

Source: author’s calculations based on the South Africa Living Conditions Survey. ‘Income Inequality And Household Debt: Examining The Impact Of Relative Income On Formal And Informal Debt In South Africa’. WIDER Working Paper 2023/37.

There are two interesting observations.

Firstly, excluding arrears to municipal authorities for services such as electricity and water supply, the poorest households borrow mostly from their family and friends.

The qualitative literature highlights that loans from family and friends are the most prevalent source of credit for small businesses, even for individuals that start their own moneylending businesses. More generally, informal credit is the main credit source for small to medium-sized businesses and smallholder farms, particularly in rural areas and among female entrepreneurs, who tend to have less access to credit than their male counterparts. Credit from informal sources has therefore been put to productive use and has positive impacts on job creation, living standards, and future income security, especially for women in South Africa.

Other studies note that a lot of people take up informal credit simply to procure household stability—for example, they send money to their village to build a house, pay for children’s school fees, or buy household supplies.

Secondly, goods on layaway or hire purchase account for larger percentages of debt as we move up the income distribution.

Buying goods on hire purchase has served two main purposes. It has served as a means to ‘fulfil aspirations to sophistication and modernity’, particularly for Black and Coloured households that have traditionally been excluded from property ownership and formal sector credit due to Apartheid. But, for some communities, it is also seen as an investment in future financial security. Parents, for example, may buy furniture or household items on hire purchase as part of their daughter’s trousseau or dowry as she marries, thereby allowing her to start her marriage on ‘the right foot’ and eventually secure a better life for her immediate and extended families.

Borrowing among South African households serves a variety of purposes. The poorest households borrow predominantly to purchase necessary goods or invest in small-scale business ventures. While households positioned higher in the income distribution also borrow to secure future financial stability, their borrowing is also characterized by a desire to keep up with their richer neighbours.

A few important implications follow. Firstly, the mainstream view of poor households as financially irresponsible is false, at least in the South African case. Secondly, increased access to formal financial credit for poorer households may improve their living standards. Finally, the results imply that social transfers to low-income households can have a more significant impact on economic output when income inequality is high. The South African government should therefore continue to invest in directed welfare transfers.

Shakeba Foster is a PhD candidate in international development at King’s College London. Her current research focuses on income inequality, informality, and recession recovery in emerging economies.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network